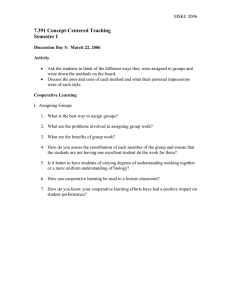

Weisner Revisited: A Reappraisal of a Co

advertisement