Link to PDF full text - Nova Scotia Barristers` Society

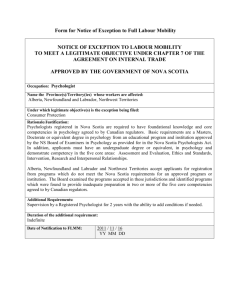

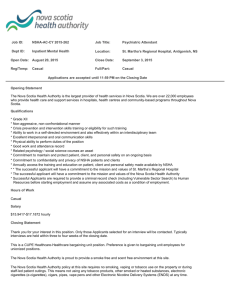

advertisement