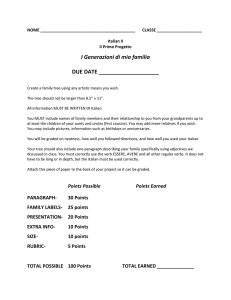

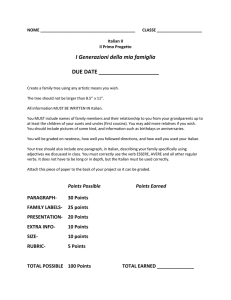

Italian Families and Social Capital

advertisement