Optimisation of the interconnecting network of a UMTS radio mobile

advertisement

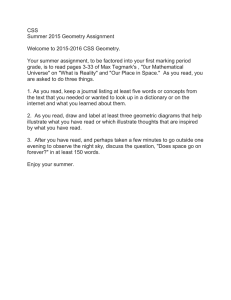

European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 www.elsevier.com/locate/dsw Discrete Optimization Optimisation of the interconnecting network of a UMTS radio mobile telephone system Matteo Fischetti a,* a , Giorgio Romanin Jacur a, Juan Jose Salazar Gonz alez b DEI, University of Padova, Via Gradenigo 6/a, 35131 Padova, Italy b DEIOC, University of La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Received 30 November 2000; accepted 18 October 2001 Abstract In this paper we address a very important optimisation problem arising in the telecommunication field, namely the design of the interconnecting network of a UMTS radio mobile telephone system. For this NP-hard optimisation problem we propose a new mixed-integer linear programming model, as well as several classes of additional constraints meant at improving the performance of solution algorithms and the quality of the lower bounds produced. Afterwards, we introduce an exact solution procedure in the branch-and-cut framework, and evaluate it on a library of real-life test problems provided by CSELT, a major research laboratory operating with an Italian telephone operator (TELECOM Italia). We report on our computational experience on these test instances, showing that the method we propose is capable of finding tight lower bounds and approximate solutions for real-world instances, within acceptable computing time. 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Communication; Location; Mixed integer linear models 1. Introduction A mobile radio telephone system aims at ensuring secure communications between mobile terminals and any other type of user device, either mobile or fixed. A mobile customer should be reachable at any time and in any location where the radio coverage is granted. The connection among mobile terminals (i.e., the user’s handheld terminals) and fixed radio base * Corresponding author. Tel.: +39-049-827-7824; fax: +39049-827-7826. E-mail address: fisch@dei.unipd.it (M. Fischetti). stations is obtained by means of radio waves. However, a single antenna system cannot cover the whole service area. In fact, that choice would require high irradiation power both from the fixed and the mobile stations, with consequent possible damage due to the generated electromagnetic field. The above limitations lead to the implementation of ‘‘cellular systems’’, constituted by several fixed radio base stations and related antenna systems. Each single radio base station coverage area is called ‘‘cell’’ and it serves a small region of variable size ranging from 10 to 100 m (high user density inside business buildings) to 1–20 km (low user density areas in the country). 0377-2217/03/$ - see front matter 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 3 7 7 - 2 2 1 7 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 3 8 3 - 6 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 Every fixed radio base station, usually called base transceiver station (BTS), is both transmitting and receiving signals on a variable number of frequencies. Depending upon the type of system considered and the radio access scheme, each frequency (or carrier) permits the allocation of a variable number of channels; in the GSM case, each frequency carries eight channels. Whenever a user moves from a cell to an adjacent one during a communication, a new channel is assigned inside the cell just entered. This feature is commonly called handover. Covering the served region with several cells allows for ‘‘frequency reuse’’, i.e., for the use of the same frequency inside two or more non-interfering cells. The users’ mobility causes issues related to the user location detection and to cell change, which are managed by equipment implementing the interface between the BTS and the fixed network. Third generation mobile telecommunication systems are currently in the course of standardisation in Europe under the name of universal mobile telecommunication system (UMTS). The basic architecture of a UMTS network includes the following devices: • Mobile terminal (MT) of different types (e.g., phone, fax, video, computer). • Base transceiver station (BTS) interfacing mobile users to the fixed network; a BTS handles users’ access and channel assignment. Due to the inherent flexibility featured by next generation BTSs, different network topologies can be undertaken: the BTS can be either directly connected to the switching equipment (smart BTS) or linked to a BTS controller (CSS). • Cell site switch (CSS), which is a switch connected to several BTSs on one side and to a single local exchange (LE) (see below) on the other side; each CSS is devoted to the management of local traffic inside its controlled area, as well as to the connection of the controlled BTSs to the LE. • LE, which is a switch connecting the BTSs to the network, either directly or through CSSs. 57 • Mobility and service data point (MSDP), which is a database where information about users is registered; it may be located either together with an LE or with a CSS, according to a centralised or distributed connection management. • Mobility and service control point (MSCP), which is a controller to manage mobility; it can access the database to read, write or erase information about users, and is generally associated with LEs and MSDPs. In this paper we address the problem of optimising a UMTS interconnection network having a multilevel star-type architecture. This is a difficultto-solve (NP-hard) optimisation problem of crucial importance in the design of effective and low-cost networks. The general characteristics of UMTS and related standardisation problems were presented in [2,3,9,17]; some hints in design and optimisation may be found in [1,4,5,8,14], but they concern either different application fields or simpler network topologies with respect to the ones studied here. As to the literature on various location problems, we refer the reader to Labbe and Louveaux [12] for a recent annotated bibliography. Facility location problems related to the one studied in the present paper have been very recently addressed in Chardaire et al. [7], where an uncapacitated twolevel network design problem is studied, and in Klose [11], where a Lagrangean heuristic based on the relaxation of the capacity constraints is proposed. The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2 we give a more detailed description of the UMTS multilevel architecture. A mixed-integer linear programming model is proposed in Section 3, and a possible solution algorithm in the branch-andcut framework is outlined. Some improvements of the basic model are presented in Section 4, where new families of valid inequalities are introduced along with the corresponding separation algorithms. Computational results on a library of realworld test problems provided by CSELT, a major research laboratory operating with TELECOM Italia, are reported in Section 5. Some conclusions are finally drawn in Section 6. 58 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 2. The UMTS multilevel architecture In the problem we consider, a certain number of potential CSS and LE sites is given, among which the planner has to choose those to be actually activated. We consider a three level star-type UMTS architecture, defined by an upper layer made up of active LEs (chosen in the given set of potential LEs), a middle layer made up of active CSSs (also chosen in the given set of potential CSSs), and a lower layer made up of the given BTSs (each of which is required to play the role of a leaf in the star-type structure). Fig. 1 illustrates a situation where 2 (out of 5) LEs and 4 (out of 6) CSSs are activated, and define a feasible star-type architecture to serve the 17 given BTSs. Note that each activated LE plays the role of the root of a tree spanning a different connected component. Moreover, the problem cannot be decomposed in two independent subproblems consisting of assigning LEs to CSSs and CSSs to BTSs, respectively, in that the choice of the active CSSs and of their traffic load creates a tight link between the two subproblems. Each BTS has to be connected to the core network, either through a single active CSS or directly to a single active LE (for certain pre-specified BTSs the direct connection to an LE can however be forbidden). Every BTS is characterised by its geographical location, its carried traffic, the number of channels required, and by its type. The BTS location is the result of a complex planning process which is not considered in this paper. The BTS carried traffic and number of channels depend on the expected average number of users served by the cell. More precisely, the traffic is the total transmitted information, and the number of channels is the number of independent simultaneous communications, each supported by a communication module (64 kbit/seconds). Every CSS is connected to the network through a single LE. Channels between a BTS and a CSS or an LE must be packed into ‘‘modules’’ of a given capacity (maximum number of channels in a module). In the plain pulse code modulation (PCM) hierarchy each module collects up to 30 channels at 64 kbps thus granting a capacity of 2 Mbps. The type depends on the connection either to an LE or to a CSS, as seen above. Costs implied by a BTS concern: • the equipment cost; • the actual connection cost, depending on the connected CSS or LE; the cost is assumed to be linear in the number of used modules. Every CSS is characterised by its type, its location, its traffic capacity, the maximum number of BTSs and modules that can be supported. CSSs may be of two different types, namely ‘‘simple’’ (type 1) or ‘‘complex’’ (type 2), having different load and cost characteristics. Costs implied by a CSS concern: • the plant cost, depending on the type of the equipment and on the location; • the connection cost, depending on the connected LE; this cost is linear in the number of used modules. Fig. 1. The three level star-type UMTS architecture. Every LE is characterised by its location, its traffic, and by the maximum number of supported PCM modules. M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 Costs implied by an LE concern: • the plant cost, depending on the location. Feasibility constraints are either of the ‘‘congruence type’’, imposing that any connection is permitted only between activated sets, or of the ‘‘limitation type’’, imposing that the traffic through any activated set is limited by the given bounds, both in terms of transmitted information and in terms of connected modules. The problem then consists of choosing the CSS and LE to be activated, and the way to connect them to the BTSs and between each other, so as to produce a feasible three-level network of minimum cost (a more detailed description is given in the next section). This combinatorial optimisation problem is strongly NP-hard, as it generalises the classical (also strongly NP-hard; see e.g. [12]) Facility Location Problem. 3. A mixed-integer linear programming model We next introduce a mathematical model for the problem, based on the following input data. We consider a set of n BTS locations, a set of m potential type 1 or 2 CSS locations, and a set of p potential LE locations. A BTS in location i produces a traffic flow tiBTS through diBTS communication channels. Channels to an LE are packed into ‘‘modules’’ (cables or microwave). If Q is the largest number of channels that can be arranged in a module, then the BTS in location i requires eBTS :¼ ddiBTS =Qe modules, i where dre ¼ minfi 2 N : i P rg denotes the upper integer part of a given real number r. It is worth observing that Q may in some cases depend on the location that a particular module is connecting. A CSS in location j of type h 2 f1; 2g can provide a traffic flow not larger than a given upper bound TjCSS-h , can support a number of modules not larger than EjCSS-h , and a number of BTSs not larger than NjCSS-h . An LE in location k can provide a traffic flow not larger than a given upper bound TkLE , and can support a number of modules not larger than EkLE . 59 BTS type is pre-defined as basic (it must be connected to a CSS), or isolated (it must be connected directly to an LE), or free (it can be connected to a CSS or directly to an LE). The fixed cost required to open a CSS of type h in location j is fjCSS-h , and the cost to open an LE in location k is fkLE . The fixed cost to activate a BTS in location i and to connect it to a CSS is fiBTS-CSS , whereas the fixed cost is fiBTS-LE in case the BTS is connected directly to an LE. The fixed cost to lay out one module from the BTS in location i to a CSS in location j is cBTS-CSS . The fixed ij cost to lay out one module from the BTS in location i to the LE in location k is cBTS-LE , and the ik fixed cost to lay out one module from a CSS in location j to the LE in location k is cCSS-LE . jk Certain (pre-specified) module connections are not possible because of the distance or other technical limitations. The problem consists in selecting the CSSs and LEs that must be actually installed and the way to connect them (and the BTSs) through PCM modules so as to support all the traffic flows going from the BTSs to the LEs, without violating the given bound limits and minimising the sum of the fixed and module costs. Our model is based on the following 0–1 decision variables: • yjCSS-h ¼ 1 iff a CSS of type h 2 f1; 2g is opened in location j; • ykLE ¼ 1 iff an LE is opened in location k; • xBTS-CSS ¼ 1 iff the BTS in location i is assigned ij to a CSS in location j; • xBTS-LE ¼ 1 iff the BTS in location i is assigned ik to the LE in location k; • xCSS-LE ¼ 1 iff a CSS in location j is assigned to jk the LE in location k. The model also needs the following nonnegative integer variables: • zCSS-LE number of modules from a CSS in j to jk the LE in k along with the following nonnegative continuous variables: • wCSS-LE traffic flow from a CSS in j to the LE jk in k. 60 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 n X The model then reads: m X X minimise fjCSS-h yjCSSh þ þ i¼1 þ i¼1 þ cBTS-CSS eBTS ij i þ fiBTS-CSS xBTS-CSS ij for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; cBTS-LE eBTS ik i þ fiBTS-LE m X xBTS-LE ik þ j¼1 p X xBTS-LE ik TiBTS xBTS-CSS ij X 6 k¼1 h¼1;2 yjCSS-h for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; ð10Þ ð11Þ xBTS-CSS ij 6 NjCSS-h yjCSS-h ð2Þ X eBTS xBTS-CSS 6 i ij EjCSS-h yjCSS-h h¼1;2 for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; diBTS xBTS-CSS 6Q ij ð3Þ p X zCSS-LE jk k¼1 i¼1 for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; ð4Þ zCSS-LE 6 Mjk xCSS-LE jk jk for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; n X ð5Þ TiBTS xBTS-CSS 6 TkLE ykLE ik i¼1 for k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; for k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; 2 f0; 1g for i ¼ 1; . . . ; n; j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; xBTS-LE 2 f0; 1g for i ¼ 1; . . . ; n; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; ik for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; zCSS-LE P 0 and integer jk h¼1;2 wCSS-LE þ jk yjCSS-h 2 f0; 1g for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; h ¼ 1; 2; xCSS-LE 2 f0; 1g jk X i¼1 j¼1 X xBTS-CSS ij ð1Þ for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; m X h¼1;2 p X ykLE 2 f0; 1g TjCSS-h yjCSS-h h¼1;2 i¼1 n X yjCSS-h 6 1 for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; xCSS-LE ¼ jk ð0Þ for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; n X ð9Þ k¼1 i¼1 n X eBTS xBTS-CSS 6 EkLE ykLE i ik i¼1 X ¼1 for i ¼ 1; . . . ; n; n X n X ð8Þ for k ¼ 1; . . . ; p; cCSS-LE zCSS-LE jk jk k¼1 xBTS-CSS ij zCSS-LE þ jk j¼1 subject to m X ð7Þ 6 Fjk xCSS-LE wCSS-LE jk jk k¼1 p m X X j¼1 for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; j¼1 p n X X wCSS-LE jk k¼1 i¼1 fkLE ykLE p X j¼1 j¼1 h¼1;2 n X m X p X TiBTS xBTS-CSS ¼ ij ð6Þ for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p: Constraints (0) force every BTS to be connected to either a CSS or an LE. Constraints (1) impose the limit on the traffic flow provided by a given CSS, (2) impose that on the number of BTSs connected to a given CSS, whereas (3) impose the limit on the number of modules connected to a given CSS. Inequalities (4) are congruence relations between xCSS-LE and zCSS-LE variables, also jk jk used to impose the bound on the number of modules connected to a given CSS. Constraints (5) force to zero zCSS-LE whenever xCSS-LE is zero; value jk jk Mjk is a given upper limit on the number of modules between j and k. Constraints (6) are used to bound the traffic flow provided by a given LE, whereas (7) impose that all traffic entering a CSS must be distributed to an LE. Similarly, (8) force to zero wCSS-LE whenever xCSS-LE is zero (value jk jk Fjk being a given upper bound on the traffic flow M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 between j and k), whereas (9) limit the number of modules connected to a given LE. Constraints (10) impose that no more than one CSS can be activated in a given location, whereas (11) force to activate every CSS connected to an LE. Clearly, all variables associated with infeasible situations (too long connections, basic/isolated BTSs, etc.) have to be fixed to 0 and removed from the model. 4. Model resolution The mixed-integer linear programming model presented in the previous section revealed very difficult to solve to proven optimality, even by using state-of-the-art methods from Mathematical Programming and Operations Research (see Section 6 for details). This is mainly due to the interaction of two hard substructures, one associated with the 0–1 x- and y-variables and the other with integer z-variables, which notoriously leads to hard-to-solve models. Nevertheless, instances of small size can hopefully be solved exactly within acceptable computing time, thus providing useful insights on the structure of the optimal solutions on real-world test problems. Even more importantly, the solution of the linear programming relaxation of the model – obtained by disregarding the integrality requirements on the x-, y- and z-variables – can be performed efficiently in short computing time, and always provides a lower bound (i.e., an optimistic estimate) of the actual minimum cost. This lower bound is therefore very useful to evaluate the quality of the approximate/heuristic solutions provided by the practitioners or by ad hoc heuristic procedures. We have therefore designed an exact solution method, which can also be used as a heuristic if it is stopped before convergence. The method follows the branch-and-cut paradigm, consisting of a tight integration between cutting plane and enumerative techniques. The reader interested in the branch-and-cut methodology is referred to Padberg and Rinaldi [16], and to Caprara and Fischetti [6] for a recent annotated bibliography. 61 The whole package allows for a tight integration with the computer codes currently in use at CSELT, the major Italian research laboratory that partially supported the present research. Our code reads the input data, in the appropriate format, possibly along with a heuristic solution. On output, the code returns the best solution found, in a format which allows for a graphical display, along with the best lower bound available (either the optimal solution value or the minimum lower bound associated with the active sub-problems in the branching queue). 5. Model improvement A main characteristic of branch-and-cut methods consists on the possibility of improving the model quality at run time, by introducing into the current model new valid inequalities (i.e., linear constraints satisfied by all feasible solutions of the problem at hand) acting as cutting planes. These linear inequalities are indeed (valid but) redundant in the original model when the integrality condition on the variables is imposed, but become useful during the solution process when the integrality condition is relaxed. In order to actually embed into the model any new class of inequalities, one has to be able to solve the associated separation problem, which can be formulated as follows: Given a family F of valid inequalities along with a (possibly fractional) solution (x ; y ; z ; w ) of the current model, find a member of family F which is violated by (x ; y ; z ; w ), or prove that none exists. We have designed the following main classes of valid inequalities, along with the corresponding separation procedures. 5.1. Logical constraints xBTS-CSS 6 ij X yjCSS-h h¼1;2 for i ¼ 1; . . . ; n; j ¼ 1; . . . ; m ð12Þ 62 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 (if a BTS i is connected to a certain CSS j, then CSS j has to be deployed). 6 ykLE xBTS-LE ik for i ¼ 1; . . . ; n; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p ð13Þ (if a BTS i is connected to a certain LE k, then LE k has to be deployed). xCSS-LE 6 ykLE jk for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m; k ¼ 1; . . . ; p ð14Þ (if a CSS j is connected to a certain LE k, then LE k has to be deployed). We also considered the following trivial constraints, which proved to be of some use for smallsize instances. X yjCSS-h 6 h¼1;2 p X zCSS-LE jk for j ¼ 1; . . . ; m ð15Þ k¼1 (at least one module must be connected to every active CSS); p X ykLE P 1 ð16Þ k¼1 (at least one LE must be deployed). All the above constraints can be efficiently separated, by enumeration. 5.2. Generalised cover inequalities Recall that dre ¼ minfi 2 N : i P rg denotes the upper integer part of a given real number r. The family of generalised cover inequalities we propose reads & ’ ! p X X X BTS BTS-CSS di =Q xij zCSS-LE jCj þ 1 6 jk i2C i2C for every C f1; . . . ; ng; j ¼ 1; . . . ; m: k¼1 ð17Þ This family of constraints imposes – in a combinatorial way – a tight lower bound on the number of PCM modules connected to a certain CSS. To prove the validity of constraints (17) for our problem, consider any given CSS j. For every subset C of BTSs we have two cases: • not all the BTSs inPC are connected to the CSS in j: in this case, i2C xBTS-CSS 6 jCj 1, hence ij the inequality left-hand side becomes non-positive and the inequality is trivially satisfied; • all the BTSs in C are indeed connected to the P ¼ CSS in j: in this case we have i2C xBTS-CSS ij jCj, hence the constraint becomesP active and BTS correctly requires to install at least = i2C di Qe modules to connect CSS j. The family of generalised cover inequalities contains an exponential number of members. Therefore, the corresponding separation problem cannot be solved through explicit enumeration. We have implemented the following more sophisticated strategy. Assume, without loss of generality, that all traffic demands diBTS as well as Q are nonnegative integers. We consider, in turn, all possible CSSs j ¼ 1; . . . ; m. For each given j, our order of business is to find a BTS subset C whose associated generalised cover inequality (17) is maximally violated. This is a hard optimisation problem in itself, that we approach through the following scheme. P Let gj :¼ ð pk¼1 zCSS-LE Þz¼z denote the rightjk hand side value of (17) computed for the solution ðx ; y ; z ; w Þ to be separated, with respect to the CSS j under consideration. We consider, in sequence, all integer values d P 1 to play the Ppossible BTS role of d =Q , and for each fixed d we i2C i look for a BTS subset C with X diBTS > Qðd 1Þ i2C and such that fj ðdÞ :¼ jC j X i2C ! xBTS-CSS ij x¼x is a minimum: if d ð1 fj ðdÞÞ > gj , then we have found a (most) violated generalised cover inequality, otherwise no such violated inequality exists for the given pair (j; d), and we proceed by considering the next value for d and/or j. The problem of determining C can now be viewed as a 0–1 Knapsack Problem (KP), in minimisation form, in which BTSs i ¼ 1; . . . ; n correspond to items, each having a nonnegative cost ð1 xBTS-CSS Þx¼x and a nonnegative weight diBTS , ij M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 and one calls for a minimum-cost item subset whose global weight is, at least, Qðd 1Þ þ 1. This knapsack problem, although NP-hard, can in practice be solved very quickly through specialised codes (see, e.g, [15]). In addition, one can typically remove/fix a large fraction of items from the knapsack problem by using standard pre-processing criteria. In particular, items j with KP cost ð1 xBTS-CSS Þx¼x ¼ 0 can always be selected in the ij knapsack as they do not deteriorate the objective function value, while contributing in a positive way to increase the overall weight of the selected items. In addition, any item j with cost ð1 xBTS-CSS Þx¼x P 1 gj =d can be removed from the ij item set, in that its choice would imply a KP cost fj ðdÞ P ð1 xBTS-CSS Þx¼x P 1 gj =d, hence it canij not lead to a violated generalised cover inequality. This latter reduction criterion typically allows one to remove a very large fraction of the items (all those with cost ðxBTS-CSS Þx¼x 6 gj =d, including ij BTS-CSS those with ðxij Þx¼x ¼ 0). According to our scheme, the separation algorithm for generalised cover inequalities requires the solution, for each CSS j ¼ 1; . . . ; m, of a sequence of knapsack problems with different knapsack capacities depending on the parameter d. Clearly, all values d 6 gj are not worth trying as they correspond to KPs with empty item set after the above reductions (in our separation context we always have x 6 1, hence d 6 gj implies ðxBTS-CSS Þx¼x 6 1 6 gj =d for all j). On the other ij hand, according to our computational experience, values d P gj þ 1 seldom produce violated cuts. Therefore we decided to only address the case d ¼ dgj e for all CSSs j with fractional gj , thus solving, at most, one knapsack problem for each j ¼ 1; . . . ; m. 6. Computational results The performance of our branch-and-cut method has been tested on a class of real-life test problems provided by CSELT. Our main goal was to evaluate the quality of the heuristic solutions computed by CSELT by means of their proprietary tabu-search method [13], that works as follows. 63 An initial (possibly infeasible) low-cost partial solution is first obtained by a simple greedy procedure that allocates every BTS to the CSS or LE which minimises the linking cost, without taking capacity constraints into account. Thereafter, a reallocation procedure is applied to try to reduce the degree of infeasibility of the resulting partial solution. More specifically, if some traffic constraint happens to be violated at a certain CSS or LE, then the associated BTSs are considered according to a decreasing sequence of required traffic, and reallocated to a different CSS or LE. A similar procedure is applied for the violated module constraints, if any. The allocation of CSSs to LEs is performed in a similar way. During tabu search, every solution is evaluated by taking into account its overall cost plus nonlinear penalties for violated constraints. The following main tabu-search moves have been implemented: (1) inactivation of an active CSS, to be chosen among the seven less utilised ones, with consequent reallocation of its associated BTSs at minimum total overall cost; (2) inactivation of an LE, to be chosen among the three less utilised ones, with reallocation of all its associated CSSs and BTSs at minimum total overall cost; (3) activation of a new complex CSS, to be chosen among seven randomly selected ones, with consequent reallocation of some BTSs; (4) activation of a new LE, to be chosen among three randomly selected ones, with consequent reallocation of some CSSs and BTSs; (5) type change of a CSS, i.e., replacement of a simple CSS by a complex one or vice-versa, possibly followed by a consequent BTSs reallocation; (6) reallocation of a BTS currently allocated to one of the five most utilised CSSs and LEs; (7) allocation swap between two BTSs. As customary, the tabu search alternates between an ‘‘exploration phase’’ characterised by low penalties for infeasibilities, and an ‘‘intensification phase’’ characterised by very high infeasibility penalties. Whenever no feasible solution is found after 20 moves, diversification is performed by exchanging active CSSs and LEs with non-active ones, while reallocating some BTSs in a vein similar to that used for the initialisation. The whole procedure ends when a predefined maximum 64 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 number of moves (10,000, in the current implementation) has been performed. As to our branch-and-cut algorithm, it was implemented in C language using the general-purpose branch-and-cut framework MINTO 3.0 [18] linked with the commercial LP solver CPLEX 5.0 [10], and was run on a PC Pentium 133 MHz under Windows 95. All internally generated cuts of MINTO have been deactivated, but we used the MINTO internal primal heuristics. Moreover, the value of the tabusearch heuristic solution is used as the initial upper bound for the branch-and-cut search. The cutting-phase generation was implemented as follows: constraints (0) are handled statically, i.e., they are present in all solved LPs. As to the remaining constraints, they are generated dynamically (i.e., they are separated on-the-fly and appended to the current LP), according to the following scheme. We first separate constraints (1), (4) and (7); if no such cut is violated, we consider constraints (12)–(14). If none of the above cuts has been generated we apply, in sequence, the separation procedures for cuts (2), (3), (5), (6), (8), (9), (10), (11), (15), (16), and (17); the separation sequence is broken as soon as violated inequalities in the current family are found. All instances in our test bed have been provided by CSELT [13]. Table 1 reports the size of the problem instances we considered (BTS-CSS-LE), the value of the initial tabu-search heuristic solution computed by the CSELT code [13] (Tabu UB), the value of the best solution found by the branch-and-bound code (Best UB), the value of the final lower bound available at the end of the enumeration, computed as the minimum lower bound associated with active nodes in the branching queue (Final LB), and the percentage gap between the initial tabu-search solution and the final lower bound (gap). The results were obtained by running our code on a PC Pentium 133 MHz with a time limit of 2 hours for each instance, which is about 2–3 times larger than the running time of the tabusearch heuristic. According to the table, the tabu-search solution and the lower bound are quite close one to each other, which validates the effectiveness of both the tabu-search heuristic and the lower bound procedures. In addition, in 11 out of the 14 cases in our test-bed the heuristic solution delivered by our branch-and-cut code was strictly better than the tabu-search one, i.e., the computing time spent in the enumeration improved both the initial lower bound and upper bound. More information on the cutting phase of branch-and-cut code is given in Table 2, where we report the actual number of the constraints (0)–(17) that have been generated during the whole run. According to the table, most of the generated cuts are logical constraints of type Table 1 Upper and lower bound comparison (2-hour time limit on a PC Pentium 133 MHz) A B C D E F G H I L M N O P BTS CSS LE Tabu UB Best UB Final LB Gap (%) 100 95 110 96 105 115 100 110 100 120 90 85 100 85 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 3 4 3 3 19,850,255 18,917,721 23,215,028 19,088,121 20,683,960 23,975,503 19,840,342 23,220,740 19,838,083 24,927,101 18,179,351 16,981,990 19,850,259 16,624,947 19,850,255 18,915,544 23,214,196 19,087,437 20,680,389 23,967,148 19,840,342 23,220,740 19,835,722 24,925,856 18,178,546 16,981,213 19,849,892 16,624,227 19,606,797.0 18,687,073.3 21,560,353.6 18,847,882.4 20,523,362.4 22,508,426.1 19,580,270.7 21,573,970.3 19,592,028.3 23,559,843.3 17,804,722.9 16,863,167.4 19,603,163.5 16,510,956.5 1.23 1.21 7.12 1.26 0.76 6.09 1.31 7.09 1.23 5.48 2.06 0.70 1.24 0.68 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 65 Table 2 Number of constraints generated during each branch-and-cut run A B C D E F G H I L M N O P (0) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) Total 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 4 2 1 3 2 5 5 4 6 2 2 2 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 29 14 22 30 18 24 28 20 28 16 20 19 17 16 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 3 4 3 2 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 40 21 41 32 30 59 55 57 88 36 20 29 22 12 4 2 3 5 4 5 5 3 3 4 3 3 3 1 0 1 3 0 0 2 0 4 0 2 0 0 0 0 12 9 14 10 10 15 14 16 25 12 9 10 10 6 284 253 324 247 255 348 334 360 522 272 234 237 254 191 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 40 42 27 40 41 41 56 48 59 74 31 24 30 23 14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 17 10 2 12 2 3 16 1 0 10 17 1 0 0 485 379 510 425 407 582 567 593 852 437 369 376 373 308 Table 3 Details on the solved LPs (execution on a PC Pentium 133 MHz) A B C D E F G H I L M N O P Nrows Ncols LB (0)–(11) LB (0)–(16) Con 0–1 Int Mar #LPsol LP time Nodes 282 222 308 263 262 362 334 368 531 287 206 223 223 165 1137 810 1414 930 988 1655 1352 1645 2450 1325 753 773 887 597 19,469,735.9 18,448,913.8 21,515,078.2 18,652,790.5 20,455,408.3 22,457,993.3 19,436,571.1 21,519,608.1 19,426,423.6 23,514,555.6 17,549,290.0 16,537,560.2 19,458,326.9 15,869,751.1 19,604,811.5 18,685,814.2 21,559,367.0 18,842,099.9 20,513,526.2 22,506,079.7 19,578,622.2 21,573,374.2 19,591,797.9 23,559,396.9 17,802,542.0 16,861,677.1 19,595,141.0 16,511,182.4 46 30 47 45 41 66 64 69 123 38 24 32 25 18 1047 754 1322 843 911 1523 1226 1509 2204 1250 706 713 840 565 46 30 47 45 41 66 64 69 123 38 24 32 25 18 484 356 485 383 391 554 542 591 813 449 353 373 365 327 9597 12,286 5416 10,637 6627 6366 6202 6107 1911 7780 12,149 9703 9113 8918 6779.86 6671.12 6932.52 6488.30 6327.81 6645.27 6795.24 6803.12 6748.90 6807.39 6924.60 6863.00 6600.37 6521.13 3531 4492 1993 3938 2627 2350 2326 2037 616 2881 4324 3677 3452 3610 (12) and (14), whereas constraints (3) and (15) play no role in the solution of the instances in our testbed. Table 3 addresses the size and structure of the several LPs solved during the MINTO branchand-cut execution; the lower bounds attainable offline (i.e., with no enumeration) when solving the LP relaxation of model (0)–(11) and of model (0)– (16), respectively, are also reported. The table columns have the following meaning: • Nrows ¼ maximum number of rows in the solved LPs; • Ncols ¼ maximum number of columns in the solved LPs; • LB (0)–(11) ¼ root-node lower bound when using model (0)–(11); • LB (0)–(16) ¼ root-node lower bound when using model (0)–(16); • con ¼ number of continuous variables; • 0–1 ¼ number of binary variables; • int ¼ number of (general) integer variables; • mar ¼ maximum number of rows in an LP, including Eq. (0); • #LPsol ¼ number of solved LPs; • LP time ¼ CPU time (over 2 hours) spent within by LP solver (CPLEX 5.0), in Pentium/133 seconds. • Nodes ¼ number of evaluated nodes in the MINTO branch-and-cut tree. 66 M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 Table 4 CPLEX 5.0 vs CPLEX 7.0 (24-hour time limit on a PC Pentium 133 MHz) CPLEX 5.0 A B C D E F G H I L M N O P a CPLEX 7.0 Cov Nodes Final LB Gap GUB Cov Flow MIR Gom Nodes Final LB Gap 846 666 924 789 786 1086 1002 1104 1593 861 618 669 669 495 172,462 213,425 174,204 261,253 257,627 147,129 86,216 117,129 18,705 158,881 280,013 306,225 338,307 1,022,674 19,508,813 18,484,704 21,553,849 18,696,094 20,486,598 22,493,827 19,485,359 21,564,126 19,495,698 23,545,762 17,580,268 16,570,887 19,493,983 15,900,612 1.72 2.29 7.16 2.05 0.95 6.18 1.79 7.13 1.73 5.54 3.30 2.42 1.79 4.36 107 71 241 102 113 163 191 224 307 153 113 95 137 21 78 79 173 79 78 133 167 212 320 123 100 86 95 75 61 27 148 59 73 118 153 167 145 99 75 53 65 41 13 13 31 11 10 18 10 18 7 21 17 11 13 10 23 16 22 18 11 26 23 27 30 24 11 16 17 11 1,141,998 2,138,486 208,483 1,683,437 1,678,916 260,439 242,767 129,052 44,114 442,607 1,754,076 4,639 1,766,589 2,937,534 19,706,345 18,792,123 21,649,948 18,915,122 20,630,517 22,549,819 19,684,923 21,629,391 19,632,384 23,634,251 17,914,494 16,980,960a 19,708,894 16,540,890 0.72 0.66 6.74 0.91 0.26 5.95 0.78 6.85 1.04 5.19 1.46 0.00 0.71 0.51 Optimal value for instance N, found by CPLEX 7.0 in 710 seconds. According to Table 3, the additional constraints (12)–(16) did improve the root-node lower bound significantly. Moreover, more than 90% of the overall computing time (7200 seconds) is spent within the LP solver, whereas the MINTO branching-tree management and heuristics along with our run-time separation procedures, only require a small fraction of the total computing time. Finally, we compared the performance of our ad hoc branch-and-cut implementation with that of the latest versions of powerful commercial MIP solvers that deploy built-in procedures for the separation of several classes of general MIP cuts, including the so-called cover, GUB, MIR, flow, and (mixed-integer) Gomory cuts. To this end, for each instance we generated model (0)–(11) explicitly and solved it by using, as a black-box, the commercial MIP solver CPLEX in its version 5.0 (the same version used as LP solver within our branch-and-cut implementation) and in its latest (greatly enhanced) version 7.0 [10]. The main internal CPLEX parameters have been preliminarily tuned to achieve the best average performance. As in the previous experiments, the value of the tabusearch heuristic solution was provided on input to initialise the current upper bound. However, the time limit was set to 24 (as opposed to 2) Pentium/ 133 hours, thus allowing for the exploration a much larger number of nodes. The results of the new runs are given in Table 4, where we report the number of generated cuts, the number of explored nodes, the final lower bound available after the 24-hour computation, and the percentage gap between the initial tabu-search solution and the final lower bound. We do not report the Best UB column here, in that CPLEX was able to improve the initial tabu-search heuristic value – even with the 24-hour time limit – only in case of instance N, where version 7.0 (but not 5.0) was able to converge to an optimal solution. When comparing the performance of the two CPLEX versions, we observe that the latest one (vers. 7.0) is capable of evaluating a much larger number of nodes and generates a considerable number of additional cuts (other than cover inequalities), which produced a significant improvement of the final lower bound. Actually, the final lower bound obtained with CPLEX 7.0 (but not with CPLEX 5.0) after 24 hours compares favorably with the one produced by our branch-and-cut implementation (with CPLEX 5.0) after 2 hours; see column gap in Table 1. However, as already observed, CPLEX 7.0 was able to improve the initial upper bound only for instance N. We can therefore argue that the ad hoc cuts (12)–(16) generated at run-time by our method, besides improving the lower bound, are quite effective in driving the branch-and-cut heuristics to find improved feasible solutions. M. Fischetti et al. / European Journal of Operational Research 144 (2003) 56–67 7. Conclusions We have addressed a very important optimisation problem arising in telecommunication, namely the design of a UMTS interconnecting network. For this NP-hard problem we have proposed a new mixed-integer linear programming problem as well as several classes of additional constraints aimed at improving the performance of solution algorithms. We have also outlined a solution algorithm in the branch-and-cut framework, and have evaluated it on a library of real-life test problems provided by CSELT, a major research laboratory operating with an Italian telephone operator (TELECOM Italia). We have reported our computational experience on these test instances, showing that the method we propose produces tight lower and upper bounds. The method proposed in this paper has also proved the effectiveness of the tabu-search methodology currently used by CSELT to solve interconnecting network planning issues. Future direction of work should address the issue of further improving the lower bound quality, thus allowing for the exact solution of medium- or large-size instances. Acknowledgements Work partially supported by CSELT, Torino, Italy; we thank Chiara Lepschy, Raffaele Menolascino and Giuseppe Minerva from CSELT for their collaboration and helpful suggestions. The work of the first two authors was also supported by MIUR, Italy, while the work of the third author was supported by TIC 2000-1750-CO6-02 and by PI2000/116, Spain. We thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. References [1] ACTS deliverable A016/COF/DS/P/008/al, Principles and methodologies for set-up of the fixed network infrastructure, AC 016 STORMS, 1996. 67 [2] E. Berruto, G. Colombo, A. Napolitano, From GSM to UMTS: A continuous evolution with steps of innovation, Technical Reports, CSELT, 1995. [3] E. Berruto, C. Eynard, A. Napolitano, Development trends and migration issues towards universal mobile telecommunication system, Technical Reports, CSELT, 1995. [4] R.R. Boorstyn, H. Frank, Large-scale network topological optimization, IEEE Transactions on Communications 25 (1977) 29–46. [5] E. Buitenwerf, G. Colombo, H. Mitts, P. Wright, UMTS: Fixed network issues and design options, IEEE Personal Communications 2 (1) (1995) 30–37. [6] A. Caprara, M. Fischetti, Branch-and-cut algorithms: An annotated bibliography, in: M. Dell’Amico, F. Maffioli, S. Martello (Eds.), Annotated Bibliographies in Combinatorial Optimization, Wiley, New York, 1997, pp. 45–63. [7] P. Chardaire, J.L. Lutton, A. Sutter, Upper and lower bounds for the two-level simple plant location problem, Annals of Operations Research 86 (1999) 117– 140. [8] CEC deliverable R2066/BT/PM2/DS/P/070/b2 part I, UMTS System Structure Document, RACE 2066 MONET, 1994. [9] J.S. Dasilva, B.E. Fernandes, The European research program for advanced mobile systems, IEEE Personal Communications 2 (1) (1995) 14–19. [10] ILOG CPLEX, User’s Manual, 2000. [11] A. Klose, A Lagrangean relax-and-cut approach for the two-stage capacitated facility location problem, European Journal of Operational Research 126 (2) (2000) 185–198. [12] M. Labbe, F.L. Louveaux, Location problems, in: M. Dell’Amico, F. Maffioli, S. Martello (Eds.), Annotated Bibliographies in Combinatorial Optimization, Wiley, New York, 1997, pp. 261–281. [13] A. Laspertini, Third-generation mobile telephone systems: Optimal design of the interconnecting network, Master Dissertation, University of Padova, Italy, 1997 (in Italian). [14] C.Y. Lee, An algorithm for the design of multi-type concentrator networks, Journal of the Operational Research Society 44 (1993) 471–482. [15] S. Martello, P. Toth, Knapsack Problems: Algorithms and Computer Implementations, Wiley, Chichester, 1990. [16] M.W. Padberg, G. Rinaldi, A branch-and-cut algorithm for the resolution of large-scale symmetric traveling salesman problems, SIAM Review 33 (1991) 60–100. [17] J. Rapeli, UMTS: Targets, system concept and standardization in a global framework, IEEE Personal Communications 2 (1) (1995) 20–28. [18] M.P. Savelsbergh, G.L. Nemhauser, Functional description of minto, a mixed integer optimizer, Technical Report, Georgia Institute of Technology, School of Industrial and System Engineering, Atlanta, 1995.