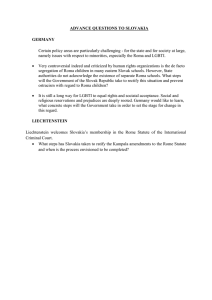

Everyday Intolerance

advertisement