Local Management Planning Guide

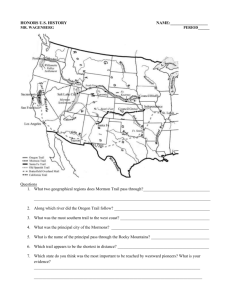

advertisement