March 2015 - New York State Dental Association

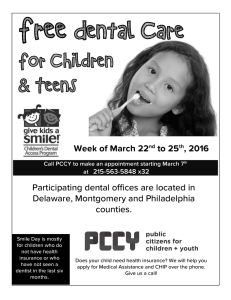

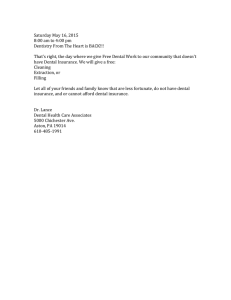

advertisement