Small GTPase Rin induces neurite outgrowth through Rac/Cdc42

advertisement

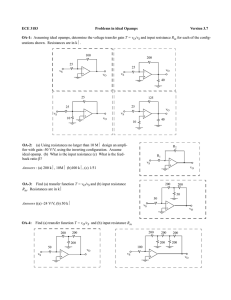

Published December 8, 2003 JCB Article Small GTPase Rin induces neurite outgrowth through Rac/Cdc42 and calmodulin in PC12 cells Mitsunobu Hoshino and Shun Nakamura Division of Biochemistry and Cellular Biology, National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo 187-8502, Japan the endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activity. Rin mutant proteins, in which the mutation disrupted association with CaM, failed to induce neurite outgrowth irrespective of Rac/ Cdc42 activation. Disruption of endogenous Rin function inhibited the neurite outgrowth stimulated by forskolin and extracellular calcium entry through voltage-dependent calcium channel evoked by KCl. These findings suggest that Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth signaling requires not only endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activation but also Rin–CaM association, and that endogenous Rin is involved in calcium/ CaM-mediated neuronal signaling pathways. Introduction The Ras superfamily small GTPases link cell surface receptors to intracellular signal transduction pathways that regulate cell growth and differentiation (Kaziro et al., 1991). The Ras protein functions as a molecular switch by cycling from the inactive GDP-bound state to the active GTP-bound state (Kaziro et al., 1991; Bos, 1998). Activation of the Ras requires several guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) which induce the dissociation of GDP to allow GTP association (Bos, 1998; Vojtek and Der, 1998; Reuther and Der, 2000). On the other hand, GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) accelerate the rate of intrinsic GTPase activities of the Ras and inactivate its biological activities (Bos, 1998; Vojtek and Der, 1998; Reuther and Der, 2000). Through its G2 effector region that is involved in the binding of specific target proteins, the activated GTP-bound Ras interacts with target proteins, such as serine/threonine kinase Raf-1, the p110 catalytic subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), the exchange factor for Ral GTPase protein RalGDS, and so on (Bos, 1998; Vojtek and Der, 1998). Address correspondence to Mitsunobu Hoshino, Division of Biochemistry and Cellular Biology, National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, 4-1-1, Ogawahigashi, Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8502, Japan. Tel.: 81-42-346-1722. Fax: 81-42-346-1752. email: hoshinom@ncnp.go.jp Key words: calcium; MAPK; Ras; Rho The newly discovered GTPase, Rin, and its Drosophila homologue Ric have been classified into the Ras superfamily (Lee et al., 1996; Wes et al., 1996; Shao et al., 1999; Reuther and Der, 2000). Rin binds GTP in vitro and exhibits an intrinsic GTPase activity (Lee et al., 1996; Shao et al., 1999). Rin shares a high sequence identity with the Ras and has a highly conserved but distinct G2 effector region (HDPTIEDAY) in which histidine is substituted for tyrosine at position 32, and alanine is substituted for serine at position 39 (Lee et al., 1996). Moreover, Rin displays unique characteristics that are not observed in other members of the Ras superfamily, such as CaM-binding activity and the lack of a typical COOH-terminal prenylation motif (CAAX motif) required for membrane association (Lee et al., 1996). Rin is expressed only in neurons and binds CaM in a calciumdependent manner (Lee et al., 1996). The expression of Rin is more prominent in the adult brain than in the brain at earlier stages (Lee et al., 1996). We demonstrated previously that Rin is activated by growth factor stimulation using a Rin pull-down assay system (Hoshino and Nakamura, Abbreviations used in this paper: CaMK, calcium/CaM-dependent protein kinase; CRIB, Cdc42/Rac interactive binding; GAP, GTPaseactivating protein; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; PAK, p21-activated kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; siRNA, short interfering RNA. The Rockefeller University Press, 0021-9525/2003/12/1067/10 $8.00 The Journal of Cell Biology, Volume 163, Number 5, December 8, 2003 1067–1076 http://www.jcb.org/cgi/doi/10.1083/jcb.200308070 1067 Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 The Journal of Cell Biology T he novel Ras-like small GTPase Rin is expressed prominently in adult neurons, and binds calmodulin (CaM) through its COOH-terminal–binding motif. It might be involved in calcium/CaM-mediated neuronal signaling, but Rin-mediated signal transduction pathways have not yet been elucidated. Here, we show that expression of Rin induces neurite outgrowth without nerve growth factor or mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Rin-induced neurite outgrowth was markedly inhibited by coexpression with dominant negative Rac/Cdc42 protein or CaM inhibitor treatment. We also found that expression of Rin elevated Published December 8, 2003 1068 The Journal of Cell Biology | Volume 163, Number 5, 2003 Results Neurite outgrowth in Rin-transfected PC12 cells To elucidate whether Rin protein is involved in neuronal differentiation, Myc epitope-tagged wild-type Rin or consti- Figure 1. Rin protein induces neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. (A) Empty vector–transfected PC12 cells were left untreated or stimulated with 50 ng/ml NGF for 44 h. Cells were fixed with 3% PFA-PBS and were visualized under a phase contrasted bright field microscopy. (B) PC12 cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding Myc-tagged wild-type Rin or Myc-tagged constitutively active RinQ78L protein. After 48 h, transfected cells were fixed, permeabilized, and processed for immunofluorescence with an anti-Myc antibody. Transfected cells were visualized with a Cy3-labeled anti–mouse secondary antibody. (C) PC12 cells were left untreated or stimulated with 50 ng/ml NGF for 2 d. Other PC12 cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding Myc-tagged wild-type Rin or Myc-tagged RinQ78L protein and were maintained for 5 d. Cells were washed with an ice-cold PBS buffer and lysed with an ice-cold lysis buffer. Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation and Western blotting was performed as described in the Materials and methods, using an antineurofilament antibody, an anti-MAPK 1/2 antibody, and an anti-Myc antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. tutively active Rin mutant (Q78L; Gln78 was replaced with Leu) was transiently expressed into PC12 cells. The cognate Q61L mutant in Ras protein is regarded as a constitutively active mutant (Vojtek and Der, 1998). As shown in Fig. 1 A, transfection of PC12 cells with a control plasmid (pEFBos empty vector) resulted in cells with a rounded morphology like that of untransfected cells. However, transfection of the wild-type Rin protein resulted in cells showing neurite outgrowth in the absence of NGF (Fig. 1 B). Constitutively active RinQ78L protein also induced neurite outgrowth in Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 2002). These studies raised the possibility that Rin plays important roles in the control of the calcium/CaM-mediated signaling pathways in the nervous system. To date, however, few of the intracellular functions and signal transduction pathways of Rin have been characterized. Rat pheochromocytoma cell line PC12 cells are a useful model system for examining mechanisms of neuronal differentiation and signal transduction (Greene and Tischler, 1976). They differentiate in response to NGF with growth arrest and show neurite outgrowth resembling that of sympathetic neurons (Greene and Tischler, 1976). After NGF stimulation, a number of signal transduction pathways in PC12 cells are activated, including the Trk receptor tyrosine kinase– Ras-MAPK cascade (Kaplan and Stephens, 1994). It has been shown that sustained MAPK activation is necessary for NGFinduced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (Marshall, 1995). The Rho GTPase family proteins, which consist of the closely related GTPases Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, participate in the actin cytoskeleton dynamics, reactive oxygen generation, and tumorigenesis (Lim et al., 1996; Bishop and Hall, 2000). In Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts, Rho regulates growth factor–stimulated stress fiber formation, whereas Rac and Cdc42 regulate growth factor–stimulated membrane ruffling and filopodium formation, respectively (Lim et al., 1996; Bishop and Hall, 2000). To date, many Rho family effector proteins have been identified. For example, the GTP-bound Rho can bind to the Rho-associated coiled-coil–forming kinases, whereas the GTP-bound Rac and Cdc42 can bind to the p21-activated kinases (PAKs) through their Cdc42/Rac interactive binding (CRIB) domain, and these kinases control the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton system (Lim et al., 1996; Bishop and Hall, 2000). CaM is a ubiquitous, highly conserved protein and is recognized as a major calcium sensor for diverse intracellular enzymes (Rhoads and Friedberg, 1997). When cells are responding to an increase in the intracellular calcium concentration, CaM undergoes a conformational change, binds to its target proteins, and evokes many cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, cytoskeletal organization, and ion channel regulation (Rhoads and Friedberg, 1997). Here, we examined the role of Rin in neuronal signaling, especially focusing on the formation and morphology of neurite processes in calcium/CaM-mediated signaling pathway. Our results showed that the expression of Rin induced neurite outgrowth without NGF stimulation or MAPK activation, and this phenomenon was markedly inhibited by coexpression with the dominant negative Rac/Cdc42 protein or treatment with CaM inhibitor. We also found that Rin proteins activated endogenous Rac/Cdc42 proteins and that Rin-induced neurite outgrowth required Rin association with CaM. Moreover, we show that endogenous Rin proteins are involved in calcium-mediated neurite outgrowth and propose that they play pivotal roles in regulating neuronal signaling pathways. Published December 8, 2003 Rin induces neurites through Rac/Cdc42 and CaM | Hoshino and Nakamura 1069 Table I. Rin-induced neurites and NGF-induced neurites in PC12 cells Total neurite length per cell (m) No. of primary processes originating from somata No. of branching points per cell Rin-induced neuritesa NGF-induced neuritesb 101.34 5.53 81.33 4.35 3.10 0.11 2.14 0.10 2.31 0.17 0.15 0.05 PC12 cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml NGF for 2 d or were transfected with a Myc-tagged wild-type Rin protein vector and maintained for 2 d. Cells were fixed, immunostained with an anti-Myc antibody, and observed by microscopy. Means SEM are shown. a n 112. b n 108. Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth is MAPK pathway independent It has been well established that the MAPK cascade is necessary for neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells (Kaplan and Stephens, 1994). We examined the activity of MAPK in Rinexpressing cells by Western blot analysis using antiphosphoMAPK antibody. As shown in Fig. 2 A, Rin-transfected cells did not show obvious MAPK activation. Moreover, pretreatment with 7.5 M U0126 (a MAPK kinase inhibitor), which concentration is sufficient for the inhibition of MAPK activity after 50 ng/ml NGF stimulation (Fig. 2 B) and of NGF-induced neurite outgrowth (Fig. 2 C), did not affect the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (Fig. 2 C). These data suggest that the MAPK pathway is not likely to be responsible for the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth is inhibited by dominant negative Rac/Cdc42 To determine whether Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth was dependent on the activity of Rho family GTPase protein, Figure 2. MAPK is not involved in the Rin-signaling pathway in PC12 cells. (A) PC12 cells were serum starved for 24 h and left untreated or stimulated with 50 ng/ml NGF or 0.5 g/ml ionomycin for 5 min. Other PC12 cells were transfected with an expression vector encoding Myc-tagged wild-type Rin or Myc-tagged RinQ78L protein and serum starved for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting as described in the Materials and methods, using an antiphospho-MAPK antibody, an anti-MAPK 1/2 antibody and an anti-Myc antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. (B) Serum-starved PC12 cells were preincubated with vehicle or various amounts of MAPK kinase inhibitor U0126 for 48 h at 37C, followed by 50 ng/ml NGF for 5 min. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting as described in the Materials and methods. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. (C) Rin-transfected cells or 50 ng/ml NGF-stimulated cells were treated with vehicle or 7.5 M U0126 for 48 h at 37C. Cells were fixed and visualized with an anti-Myc antibody. Cells with neurites exceeding one cell body diameter in length were counted as a ratio of the total number of transfected cells. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). Asterisk indicates P 0.05 as compared with the control value. we cotransfected cells with wild-type Rin and dominant negative Rac1 (RacS17N) proteins. As shown in Fig. 3 A, RacS17N suppressed the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth completely. Dominant negative Cdc42 (Cdc42S17N) protein also suppressed it completely (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, dominant negative RhoA (RhoT19N) protein suppressed it only partially (Fig. 3 B). Endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activation is required for Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth To examine whether the Rac/Cdc42 activity is required as a downstream signaling component of Rin protein, we measured the amount of GTP-bound Rac/Cdc42 in Rin-transfected cells using a pull-down assay. This assay system makes use of the CRIB domain of PAK as a GST fusion protein, Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 PC12 cells (Fig. 1 B). NGF-induced neurites showed linear extensions and few branchings (Fig. 1 A), whereas Rin-transfected cells showed multiple neurites per cell and plenty of branchings (Fig. 1 B and Table I). The multiple neurites and profuse branchings were also observed when HA-tagged Rin protein was expressed instead of Myc-Rin protein or when anti-Rin antibody was used as a primary antibody instead of anti-Myc epitope tag antibody (unpublished data). To examine whether this biological effect of Rin protein is related to the neuronal differentiation, we assessed an expression of a differentiation-associated marker protein neurofilament. Neurofilament is an intermediate filament expressed specifically in neurons and NGF is known to increase the levels of neurofilament proteins in PC12 cells (Lindenbaum et al., 1988). As shown in Fig. 1 C, the increase in neurofilament levels was observed in Rin-transfected cells as well as in NGF-treated cells, whereas the expression level of MAPK remains constant. Neurofilament proteins are barely visible in the control PC12 cell extracts (Fig. 1 C). These results suggest that Rin protein induces neuronal differentiation, at least in terms of the induction of neurofilament expression. Published December 8, 2003 1070 The Journal of Cell Biology | Volume 163, Number 5, 2003 Figure 3. Dominant negative Rac/Cdc42 inhibits the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. (A and B) Cells were transfected with an HA-tagged wild-type Rin vector and a Myc-tagged dominant negative RacS17N/Cdc42S17N/RhoT19N vector either alone or in pairs. After 48 h, cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-HA antibody and an anti-Myc antibody. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). In the merge of A, HA-Rin staining is shown in green (using FITC-labeled anti–rat secondary antibody), whereas Myc-Rac staining is shown in red (using Cy3labeled anti–mouse secondary antibody). Figure 4. Rin activates endogenous Rac/Cdc42 in PC12 cells. Cells were transfected with an empty vector or Myc-tagged expression vectors encoding several Rin proteins. After 48 h, cells were lysed and cleared, followed by Rac/Cdc42 pull-down assay, as described in the Materials and methods. Bound endogenous Rac proteins (arrow) and Cdc42 proteins were visualized by Western blotting using an antiRac antibody and anti-Cdc42 antibody, respectively. Lane 1, empty vector; lane 2, wild-type Myc-Rin, lane 3, Myc-RinQ78L; lane 4, Myc-Rin18; lane 5, Myc-RinC-4; lane 6, Myc-RinC-7; lane 7, empty vector with 50 ng/ml NGF for 3 min; lane 8, constitutively active Myc-Rac (positive control, asterisk). Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. CaM is also involved in Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth Because Rin protein has the ability to interact with CaM directly (Lee et al., 1996), we conjectured that association of Rin with CaM might be required for Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. To test this hypothesis, Rin-transfected PC12 cells were incubated with the CaM inhibitor W13. As shown in Fig. 5 (A and B), W13 could significantly inhibit the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. To exclude the possibility of nonspecific inhibitory effects of W13, we used W12, which is a structural analogue of W13 and is far less effective than W13 as a CaM inhibitor (Hidaka and Tanaka, 1983). The results showed that Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth was not affected by incubation with a concentration of W12 that was equivalent to the concentration of W13 that significantly inhibited the neurite outgrowth (Fig. 5, A and B). These data suggest that the CaM antagonist W13 has a specific inhibitory effect on the Rinmediated neurite outgrowth. A deletion mutant of Rin, Rin18, in which the COOHterminal 18 residues of the CaM-binding motif were deleted (Fig. 5 C), could no longer bind to CaM (Fig. 5 D). This Rin18 mutant activated Rac/Cdc42 to a similar degree as the full length wild-type or constitutively active Rin protein (Fig. 4, lane 4). However, the Rin18 mutant failed to exhibit neurite outgrowth activity (Fig. 5, A and E). To further confirm this observation, we constructed other CaM-binding defective mutants, which contained point rather than deletion mutation. These point mutants, named RinC-7 and RinC-4, in which all seven basic amino acid residues and four basic residues were replaced with neutral ones in the COOH-terminal of the Rin protein that was deleted in the Rin18 mutant, respectively (Fig. 5 C), also showed no binding activity to CaM (Fig. 5 D). As expected, they activated Rac/Cdc42 (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6), but failed to extend neurites in PC12 cells (Fig. 5, A and E). Together, these data strongly suggest that Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth requires both downstream Rac/Cdc42 activation and CaM association. Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 which specifically binds to and isolates the GTP-bound Rac/ Cdc42 (Benard et al., 1999). Transient expression of Rin in PC12 cells resulted in an obvious increase of the amounts of GTP-bound Rac/Cdc42 protein (Fig. 4, lane 2), when compared with the empty vector–transfected cells (Fig. 4, lane 1). The level of this activation was similar to the NGFinduced Rac/Cdc42 activation (Fig. 4, lane 7). RinQ78L protein also evoked the endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activation to the same degree as the wild-type did (Fig. 4, lane 3). These data suggest that Rac/Cdc42 is located in the downstream signaling pathway of Rin and that Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth requires endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activity. Published December 8, 2003 Rin induces neurites through Rac/Cdc42 and CaM | Hoshino and Nakamura 1071 Endogenous RhoA is activated in Rin-expressed cells To examine whether Rho is also activated by Rin, we measured the endogenous Rho activity by Rho pull-down assay. This assay system makes use of the Rho-binding domain of mDia1 as a GST fusion protein, which specifically binds to and isolates the GTP-bound Rho (Kimura et al., 2000). As shown in Fig. 6 A, an increase of the amounts of GTPbound Rho was detected in both the wild-type Rin-transfected (lane 2) and RinQ78L-transfected cell lysates (lane 3). The level of GTP-bound Rho was similar to the lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-treated cells (Fig. 6 A, lane 7). Next, we examined whether RhoA affects the morphology of Rin-expressed cells using RNA interference method. As shown in Fig. 6 B, short interfering RNA (siRNA) of RhoA eliminated the expression of RhoA protein, but did not eliminate the expression of another protein, such as Rac. Control siRNA did not eliminate the expression of RhoA protein (Fig. 6 B). These results indicate that siRNA of RhoA specifically disrupts RhoA protein expression. Disruption of RhoA function induced more branching points of Rin-induced neurites (Fig. 6 C, i.e., there were 2.84 0.08 branching points per cell for RhoA-disrupting Rin-expressed cells, compared with 2.20 0.08 branching points per cell for Rin-expressed cells; P 0.05). siRNA of RhoA itself did not induce neurites in control PC12 cells (Fig. 6 C). RhoA is supposed to function as a negative regulator for neurites and dendrite branch formation (Li et al., 2000; Nakayama et al., 2000). Our data showed that Rin-induced neurite outgrowth was not simply due to RhoA inhibition, and that Rin may regulate the neurite complexity through activation of Rac/Cdc42 and RhoA. Endogenous Rin protein is also involved in calcium-mediated neurite outgrowth To investigate the function of the endogenous Rin protein, we examined whether expression of the dominant negative Rin protein altered the function of the endogenous Rin in PC12 cells. Rin mRNA was not detected in nonneuronal Cos-7 cells but certainly existed in PC12 cells, though its mRNA level is rather lower than that of primary culture of neuronal cells (Fig. 7 A). Next, we constructed the dominant negative Rin, RinS34N, in which Ser34 was replaced with Asn. The cognate S17N mutant of the Ras, which is regarded as a dominant negative Ras, cannot bind to the effectors but binds to its GEFs and sequesters them, with the result that it cannot activate its downstream signaling cascade (Vojtek and Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 Figure 5. CaM association is necessary for Rin-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. (A, B) PC12 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged expression vectors encoding several Rin proteins and incubated with vehicle, 50 or 100 M W13 (CaM antagonist) or W12 (inactive analogue of W13). After 48 h, cells were fixed and immunostained with an antiMyc antibody. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). Asterisks indicate P 0.05. (C) Comparison of the COOH-terminal amino acid sequences (amino acids 191– 217) of wild-type Rin protein, Rin18, RinC-4, and RinC-7. The residues of the mutant proteins that are different from those of the wild-type Rin protein are italicized. (D) Cos-7 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged expression vectors encoding several Rin proteins. After 48 h, cells were lysed, cleared, and Rin proteins were pulled down with CaM-conjugated agarose beads at 4C for 2 h as described in the Materials and methods. Bound Myc-Rin protein was visualized with an anti-Myc antibody. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. (E) PC12 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged expression vectors encoding several Rin mutant proteins. After 48 h, cells were fixed and immunostained with an antiMyc antibody. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). Published December 8, 2003 1072 The Journal of Cell Biology | Volume 163, Number 5, 2003 Der, 1998). However, RinS34N has quite a low expression efficiency compared with the wild-type protein (unpublished data). Therefore, we needed to construct another Rin mutant that act in a dominant negative manner. RinG29V-C-7, in which the CaM-binding motif of the constitutively active RinG29V protein was mutated in a manner similar to that for the RinC-7 mutant, was constructed. As shown in Fig. 7 B, Myc-tagged RinG29V-C-7 could not induce the neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells because of the lack of CaM-binding ability, and it also suppressed the wild-type Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. These data suggest that RinG29V-C-7 can act as a dominant negative Rin. PC12 cells expressed RinG29V-C-7 proteins inhibit neither the NGF-induced neurite outgrowth (Fig. 7 C), nor the NGF-induced Rac/Cdc42 activation (Fig. 7 D). These data indicate that Rin is not likely to be involved in the NGFmediated signaling pathway leading to neurite outgrowth. It was reported previously that elevation of extracellular potassium evokes membrane depolarization, and that depolarization-induced calcium entry through voltage-dependent calcium channels sustains neurites and cell survival after NGF withdrawal in PC12 cells (Teng and Greene, 1993). Moreover, Mark et al. (1995) have reported that intracellular cAMP and KCl depolarization synergistically stimulate neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Therefore, we investigated whether Rin is involved in calcium entry-mediated neurite outgrowth after KCl-evoked membrane depolarization in PC12 cells. As shown in Fig. 7 E, 30% of 50 M forskolin-treated GFP-expressed cells showed neurite outgrowth. After addition of 50 mM KCl, neurite outgrowth of forskolin-stimulated cells was potentiated by KCl-evoked membrane-depolarization and subsequent calcium entry (Fig. 7 E). As demonstrated previously (Mark et al., 1995), depolarization by KCl alone showed no significant induction of neurite outgrowth (not depicted), and forskolin and KCl depolariza- tion-induced neurite outgrowth was calcium entry-dependent because it was inhibited by the L-type calcium channel blockers nitrendipine and diltiazem (Fig. 7 E). Dominant negative RinG29V-C-7 could not inhibit the forskolininduced neurite outgrowth, but could inhibit the neurite outgrowth stimulated by forskolin and KCl at the level of the stimulation of forskolin alone (Fig. 7 E). After preincubation with the L-type calcium channel blockers nitrendipine or diltiazem, RinG29V-C-7 was unable to further inhibit the neurite outgrowth stimulated by forskolin and KCl, as compared with the forskolin and KCl-stimulated blockerpretreated cells (Fig. 7 E). To confirm these findings, we examined whether Rin is certainly involved in the calcium entry-mediated neurite outgrowth by using RNA interference method. As shown in Fig. 7 F, siRNA of Rin eliminated the expression of Rin protein, but did not eliminate the expression of another protein, such as Ras. Control siRNA did not eliminate the expression of Rin protein (Fig. 7 F). These results indicate that siRNA of Rin specifically disrupts Rin protein expression. The neurite outgrowth stimulated by forskolin and KCl is inhibited at the level of the stimulation of forskolin alone after siRNA of Rin introduction (Fig. 7 G). Control siRNA did not show this inhibitory phenomenon (Fig. 7 G). These data suggested that dominant negative Rin or siRNA of Rin inhibit calcium-mediated neurite outgrowth and that Rin may be involved in the calcium-mediated signaling pathways leading to neurite outgrowth. In addition, we examined the effect of inhibiting Rac/ Cdc42 in this calcium-mediated neurite outgrowth. As shown in Fig. 7 H, dominant negative Rac or Cdc42 considerably inhibited neurite outgrowth after forskolin stimulation. Dominant negative Cdc42-expressed cells showed the potentiation of neurite outgrowth after KCl addition, and siRNA of Rin did not inhibit this potentiation further (Fig. 7 H). These data suggest that Rin requires Cdc42 signaling Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 Figure 6. Rin activates endogenous Rho in PC12 cells. (A) PC12 cells were transfected with an empty vector or Myc-tagged Rin vector. After 48 h, cells were stimulated with vehicle or 10 M LPA for 1 min. Cells were lysed and cleared, followed by Rho activation assay, as described in the Materials and methods. Lane 1, empty vector; lane 2, wild-type Myc-Rin, lane 3, Myc-RinQ78L; lane 4, Myc-Rin18; lane 5, Myc-RinC-4; lane 6, Myc-RinC-7; lane 7, empty vector with 10 M LPA for 1 min. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. (B) PC12 cells were transfected with indicated amounts of siRNA of RhoA or control siRNA. After 48 h, cells were lysed, cleared and followed by Western blotting as described in the Materials and methods. (C) PC12 cells were transfected with a Myc-tagged wild-type Rin vector and a siRNA of RhoA either alone or in pairs. After 48 h, cells were fixed and observed as described in the Materials and methods. Published December 8, 2003 Rin induces neurites through Rac/Cdc42 and CaM | Hoshino and Nakamura 1073 pathway to mediate calcium-induced neurite outgrowth. However, dominant negative Rac-expressed cells did not show the potentiation after KCl addition (Fig. 7 H). Thus, it is uncertain whether Rac is specifically required for Rinmediated calcium-induced neurite outgrowth. Discussion Here, we presented evidence that Rin protein plays an important role in neuronal calcium signaling. We found that Rin protein did not activate MAPK and that MAPK inhibi- Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 Figure 7. Endogenous Rin protein is involved in calcium-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. (A) The expression of Rin and GAPDH (constitutively expressed gene) at the mRNA level was detected by performing RT-PCR from total RNA isolated from Cos-7, PC12, and primary dissociated neuronal cells from P3 mouse brain, as described in the Materials and methods. (B) PC12 cells were transfected with an HA-tagged wild-type Rin vector and a Myc-tagged vector encoding RinG29V-C-7 mutant protein either alone or in pairs. After 48 h, cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-HA antibody and an anti-Myc antibody. In the merge, HA-Rin staining is shown in green (using FITC-labeled anti–rat secondary antibody), whereas Myc-Rin staining is shown in red (using Cy3-labeled anti–mouse secondary antibody). (C) PC12 cells were transfected with an empty vector or a Myc-tagged RinG29V-C-7 expression vector. After 4 h, transfected cells were stimulated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml NGF for 44 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-Myc antibody. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). (D) PC12 cells were transfected with an empty vector or RinG29V-C-7 expression vector. After 48 h, they were stimulated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml NGF for 5 min. Cells were lysed and cleared, followed by a Rac/Cdc42 pull-down assay (Rac PD and Cdc42 PD). Bound endogenous Rac proteins (arrow) and Cdc42 proteins were visualized by Western blotting. Constitutively active Myc-Rac (positive control) is indicated by asterisk. Data are representative of three independent experiments, which gave essentially identical results. (E) PC12 cells were transfected with an empty vector or a Myc-tagged RinG29V-C-7 expression vector. After 4 h, transfected cells were pretreated with vehicle or the L-type calcium channel blocker nitrendipine (final 10 M)/diltiazem (final 50 M) for 30 min and stimulated with 50 M forskolin alone or 50 M forskolin plus 50 mM KCl for 44 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained with an anti-Myc antibody. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). Asterisks indicate P 0.05. (F) PC12 cells were transfected with 1 g of Myc-tagged wild-type Rin vector and indicated amounts of siRNA. After 48 h, cells were lysed, cleared and followed by Western blotting as described in the Materials and methods. (G) PC12 cells were transfected with 1 g of pGFP-C1 vector and indicated amounts of siRNA. After 4 h, transfected cells were stimulated with 50 M forskolin alone or 50 M forskolin plus 50 mM KCl for 44 h. Cells were fixed and counted as described in the Materials and methods. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). The asterisk indicates P 0.05. (H) PC12 cells were transfected with 1 g of Myc-tagged RacS17N/Cdc42S17N and 1 g of pGFP-C1 vector plus 10 g of Rin-specific siRNA either alone or in pairs. After 4 h, transfected cells were stimulated with 50 M forskolin alone or 50 M forskolin plus 50 mM KCl for 44 h. Cells were fixed and counted as described in the Materials and methods. Columns and vertical bars denote the mean SEM, respectively (n 3). Asterisks indicate P 0.05. Published December 8, 2003 1074 The Journal of Cell Biology | Volume 163, Number 5, 2003 must be a linking molecule between Rin and Rac/Cdc42, or their GEFs, such as Vav or Cdc24. Because RhoG is shown to be located upstream of Rac/Cdc42 (Kato et al., 2000), we investigated whether RhoG participated in the Rin and Rac/ Cdc42 pathway using RNA interference method. As a result, RhoG is not likely to be involved in Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth (unpublished data). Identification of a molecular link between Rin and Rac/Cdc42 should be further clarified. We showed that CaM association with Rin is necessary to induce neurite outgrowth. We did not analyze the downstream target of CaM, but there is a possibility that calcium/ CaM-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs) and/or IQGAP1 are the targets. CaMKI and CaMKII are enriched in neuronal processes and synapses (Curtis and Finkbeiner, 1999), and they can phosphorylate the serine 133 of cAMP response element binding protein, a well-known transcription factor involved in synaptic plasticity (Curtis and Finkbeiner, 1999). IQGAP1 has an affinity for CaM through its IQ motif and an actin-binding protein, whose function is cross-linking the actin filaments into bundles (Hart et al., 1996). IQGAP1 is also a Rac/Cdc42 effector and serves as a direct molecular link between Rac/Cdc42 and actin filaments under the regulation of CaM (Hart et al., 1996; Bashour et al., 1997). Recently, Rac/ Cdc42 has been shown to interact with microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP-170, a microtubule plus end tracking protein, and forms a complex at the leading edge, resulting in a polarized microtubule array and cell polarization (Fukata et al., 2002). We examined whether IQGAP1 associates Rin–CaM complex and found that IQGAP1 formed a ternary complex with Rin and CaM by coimmunoprecipitation assay (unpublished data). There is a possibility that CaMK and/or IQGAP1 might contribute to the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. We found that Rho is also activated by Rin. Rho family proteins are central regulators of neuronal morphology including neurite branching (Luo, 2000). We found that Rininduced neurite has a plenty of branchings. It has been shown that Rac/Cdc42 are positive regulators for dendritic branching and remodeling whereas Rho is a negative regulator for branch formation (Li et al., 2000; Nakayama et al., 2000). It is an interesting possibility that Rin may induce the branchings of neurite by exquisite balancing between the downstream Rac/Cdc42 and Rho signaling. We investigated the function of endogenous Rin using dominant negative Rin. In RT-PCR analysis, the expression of Rin at the mRNA level in PC12 cells was low. For this reason, the endogenous Rin expression in PC12 cells was too low to detect with Western blotting using an anti-Rin antibody (unpublished data). At first, we constructed a RinS34N expression vector, but it could not be efficiently expressed in the cells, probably due to the cell toxicity of RinS34N. This fact indicates that endogenous Rin may play an important role in regulating the cell growth. Then, we made another dominant negative Rin mutant vector encoding RinG29V-C-7, which can be efficiently expressed in the cells. It was expected that RinG29V-C-7 can bind the effector molecules through their effector region but suppress signals to the downstream molecules leading to the neurite outgrowth. We have shown that dominant negative RinG29V-C-7 could not inhibit the NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. Spencer et al. (2002) demonstrated previously that domi- Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 tion did not suppress Rin-induced neurite outgrowth. Previous reports also indicated that Rin fails to activate MAPK, Jun NH2-terminal kinase or p38 kinase (Rusyn et al., 2000; Spencer et al., 2002). Kobayashi et al. (1997) showed previously that constitutively active PI3K can induce Jun NH2terminal kinase and lead to neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Because GTP-bound Ras interacts with the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K (Bos, 1998; Vojtek and Der, 1998; Reuther and Der, 2000), we examined whether Rin is able to interact with PI3K using the coimmunoprecipitation method. Although Rin and Ras share high sequence identity within the effector domains (Lee et al., 1996), we could not detect Rin interaction with the PI3K p110 subunit (unpublished data), as reported previously (Shao et al., 1999). Thus, Rin is likely to use neither the MAPK cascade nor the PI3K cascade that lead to neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. We found that wild-type Rin, as well as constitutively active RinQ78L, induced neurite outgrowth. We (Hoshino and Nakamura, 2002) and Spencer et al. (2002) observed previously that basal levels of GTP-bound wild-type Rin remains quite high and that the amount of wild-type Rin precipitated from the Cos-7 cell lysates is almost the same as that of constitutively active Rin using a Rin pull-down assay system (unpublished data). Considering that the guanine nucleotide dissociation rate of Rin is faster than that of most Ras family member (Shao et al., 1999) and that the intracellular concentration of GTP is much higher than that of GDP (McCormick, 1989), it is expected that most of Rin proteins may be remained active GTP-bound state in the cells. There may be another possibility that it might be based on low activity of RinGAP or that a specific GEF of Rin might be exist and might exhibit marked affinity and catalytic efficiency for wild-type Rin protein. Spencer et al. (2002) reported previously that neither GFP-tagged wild-type Rin nor GFP-tagged RinQ78L induces neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells, which is a subline of PC12 cells. This discrepancy may be due to the difference of the cell lines. The large size of GFP (27 K) could interfere with the distribution and function of the fusion protein. In fact, we verified that neither GFP-tagged wild-type Rin nor GFP-tagged RinQ78L induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells (unpublished data). To circumvent this problem, we transfected tiny tag-fused (Myc-tagged or HA-tagged) Rin into the pEF-Bos vector, which is a powerful mammalian expression vector (Mizushima and Nagata, 1990). We demonstrate that Rac/Cdc42 activity is required for the Rin-induced neurite outgrowth and that Rin activates endogenous Rac/Cdc42 in PC12 cells. To confirm this observation, we cotransfected cells with wild-type Rin and dominant negative PAK1 protein, one of the effector molecules of Rac/Cdc42 proteins (Zhao et al., 1998). Dominant negative PAK1 protein also suppressed the Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth. (There were 76.45 2.00% of neuritebearing cells for wild-type Rin-expressed cells, compared with 59.82 1.14 of neurite-bearing cells for dominant negative PAK1 and wild-type Rin-coexpressed cells; P 0.05). To examine whether Rin directly associates with Rac/ Cdc42, we performed the coimmunoprecipitation assay. As a result, we failed to detect the direct interaction between Rin and Rac/Cdc42 (unpublished data). Probably, there Published December 8, 2003 Rin induces neurites through Rac/Cdc42 and CaM | Hoshino and Nakamura 1075 Materials and methods Antibodies and reagents Anti–c-Myc 9E10 antibody, anti-Cdc42 antibody and anti-RhoA antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Anti-HA high affinity antibody (3F10) was purchased from Roche. Antineurofilament 160 antibody (NN18), NGF, ionomycin, LPA, W12 (N-[4-aminobutyl]-2-naphthalenesulfonamide), W13 (N-[4-aminobutyl]-5-chloro-2-naphthalenesulfonamide), nitrendipine, diltiazem, and CaM-conjugated agarose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-Rin antibody and MAPK kinase inhibitor U0126 were purchased from Calbiochem. Antiphospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-MAPK 1/2 and anti-Rac 23A8 antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from CHEMICON International, Inc. FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Zymed Laboratories. pGFP-C1 vector was purchased from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. pGEX vector and glutathione-Sepharose beads were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Expression plasmids Myc-Rin and HA-Rin mammalian expression pEF-Bos vectors were constructed as described previously (Hoshino and Nakamura, 2002). The dominant negative Rac1 vector (pEF-Bos Myc-RacS17N) and Cdc42 vector (pEF-Bos Myc-Cdc42S17N) were provided by Y. Takai (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) and H. Miki (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). Constitutively active Rin mutants (RinQ78L and RinG29V), Rin deletion mutant (Rin18), Rin point mutants (RinC-7 and RinC-4), and dominant negative Rin mutants (RinS34N and RinG29V-C-7) were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The dominant negative PAK1 vector was constructed as described previously (Zhao et al., 1998). The coding region of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Cell cultivation and transfection Cos-7 cells and PC12 cells were cultured in DME (Nissui) supplemented with 10% FBS (Intergen), 2 mM L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin, and incubated at 37C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Serum-starved cells were obtained by incubation for 24 h in the medium containing 0.5% serum. Semi-confluent cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CaM-binding assay The CaM-binding assay was performed as described previously (Hoshino and Nakamura, 2002). Measurement of endogenous Rac/Cdc42 activity The CRIB domain of PAK1 was cloned into the pGEX vector and was expressed in Escherichia coli as a fusion protein. Transfected PC12 cells were serum starved for 24 h and lysed with an ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 10 g/ml aprotinin and leupeptin). Cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 g at 4C, and each supernatant was incubated with 10 g of purified GST-PAK CRIB immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads at 4C for 30 min. After the beads were washed twice with a lysis buffer, the bound proteins were suspended in 20 l Laemmli sample buffer and separated by 14% SDS-PAGE. Measurement of endogenous Rho activity Rho pull-down assay was performed similar to the Rac/Cdc42 pull-down assay as described in the previous paragraph, using Rho-binding domain of GST-mDia1 protein instead of GST-PAK CRIB protein. The beads-bound Rho proteins were visualized by Western blotting using anti-RhoA antibody. Western blotting Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell), and probed with a primary antibody in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat dry milk (Becton Dickinson). The primary antibody was visualized with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Biosciences) and ECL (PerkinElmer). RT-PCR Total RNA was extracted from the cells using Isogen reagent (Wako). 5 g of extracted total RNA was used as a template for oligo-dT–primed firststrand cDNA synthesis using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and 2% of the resultant cDNA was used for PCR amplification. PCR was performed by 30 cycles at 94C for 1 min, 55C for 1 min, and 72C for 1 min. The primers used were as follows: for Rin, forward, 5-CTCTTGCTCGAGACTACAAC-3 and reverse, 5-CCTTCCTGCGTATTTCTCTC-3 (105 bp); and for GAPDH, forward, 5-CCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3 and reverse, 5-GCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAGC-3 (230 bp). The identity of the amplified cDNAs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Immunofluorescence and neurite outgrowth analysis 48 h after transfection, PC12 cells were washed with PBS buffer and fixed with 3% PFA-PBS for 20 min. Next, cells were membrane permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 PBS for 5 min. After the residual PFA and Triton X-100 were washed away with PBS buffer, cells were probed with a primary antibody in PBS for 2 h, followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 2 h. Stained cells were examined under appropriate illumination on a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). About 200 cells were counted at each experiment. Cells were counted as positive for neurite outgrowth if one or more neurites exceeded one cell body diameter in length. RNA interference Single-stranded RNA was synthesized by standard protocols (Elbashir et al., 2001). Complementary single-stranded RNAs were annealed by heating them to 90C and cooling to 37C. Disruption of Rin protein function was performed by transfecting double-stranded RNAs into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. We thank all members of our laboratory for their valuable suggestions and Drs. N. Suzuki, Y. Matsumoto, S. Ishii, H. Bito, and T. Shimizu for their comments and continuous encouragement. We are grateful to Drs. Y. Takai and H. Miki for providing a dominant negative Rac1 and Cdc42 vectors. We also thank Ms. H. Izumi and N. Fukumoto for their skillful technical assistance. This research was supported by an Advanced Brain Research grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture, and Technol- Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 nant negative RinS34N potently inhibits NGF-induced neurite outgrowth. This may be due to the fact that RinS34N has some toxic effect to the cells. Moreover, we (this paper) and Spencer et al. (2002) observed that neither wild-type nor constitutively active Rin induced MAPK activation. It has been shown that sustained MAPK activation is necessary for NGF-stimulated neurite outgrowth (Marshall, 1995). Thus, we consider that Rin is not likely to be a component of the NGF–MAPK pathway leading to neurite outgrowth. We have demonstrated that dominant negative RinG29VC-7 or siRNA of Rin inhibits the forskolin plus KCl-induced neurite outgrowth at the level of stimulation of forskolin alone, and that Rin exists in a calcium-mediated signaling pathway using calcium channel blockers. The importance of this calcium–cAMP signaling pathway is illustrated by Wong’s report. Wong et al. (1999) showed that calciumstimulated adenylate cyclase activity is essential for long-term memory and late phase long-term potentiation. Intracellular calcium increase through voltage-dependent calcium channels or N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors can activate calcium-sensitive adenylate cyclase, and generated cAMP can activate protein kinase A or cyclic AMP response element binding protein–mediated transcription pathway leading to long-term potentiation and memory formation (Wong et al., 1999; Poser and Storm, 2001). Thus, Rin may play a role in a long term effect on neuronal function as well as neuritogenesis. In conclusion, we have identified a novel function of Rin protein, i.e., inducing neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. However, many problems about Rin signaling, for example, whether there is a specific GEF or GAP of Rin, remains to be clarified. Further studies focusing on these problems will shed light on our understanding of the Rin-signaling pathway and its roles in the regulation of neuronal cell morphology and the functions of the nervous system. Published December 8, 2003 1076 The Journal of Cell Biology | Volume 163, Number 5, 2003 ogy, and Health Sciences Research grants from the Organization of Pharmaceutical Safety and Research and Research on Advanced Medical Technology, nano-001. Submitted: 13 August 2003 Accepted: 8 October 2003 References Downloaded from on October 2, 2016 Bashour, A.M., A.T. Fullerton, M.J. Hart, and G.S. Bloom. 1997. IQGAP1, a Rac- and Cdc42-binding protein, directly binds and cross-links microfilaments. J. Cell Biol. 137:1555–1566. Benard, V., B.P. Bohl, and G.M. Bokoch. 1999. Characterization of Rac and Cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13198–13204. Bishop, A.L., and A. Hall. 2000. Rho GTPases and their effector proteins. Biochem. J. 348:241–255. Bos, J.L. 1998. All in the family? New insights and questions regarding interconnectivity of Ras, Rap1 and Ral. EMBO J. 17:6776–6782. Curtis, J., and S. Finkbeiner. 1999. Sending signals from the synapse to the nucleus: possible roles for CaMK, Ras/ERK, and SAPK pathways in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and neuronal growth. J. Neurosci. Res. 58:88–95. Elbashir, S.M., J. Harborth, W. Lendeckel, A. Yalcin, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2001. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammarian cells. Nature. 411:494–498. Fukata, M., T. Watanabe, J. Noritake, M. Nakagawa, M. Yamaga, S. Kuroda, Y. Matsuura, A. Iwamatsu, F. Perez, and K. Kaibuchi. 2002. Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP170. Cell. 109:873–885. Greene, L.A., and A.S. Tischler. 1976. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73:2424–2428. Hart, M.J., M.G. Callow, B. Souza, and P. Polakis. 1996. IQGAP-1, a calmodulin-binding protein with a rasGAP-related domain, is a potential effector for Chc42Hs. EMBO J. 15:2997–3005. Hidaka, H., and T. Tanaka. 1983. Naphthalenesulfonamides as calmodulin antagonists. Methods Enzymol. 102:185–194. Hoshino, M., and S. Nakamura. 2002. The Ras-like small GTP-binding protein Rin is activated by growth factor stimulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295:651–656. Kaplan, D.R., and R.M. Stephens. 1994. Neurotrophin signal transduction by the Trk receptor. J. Neurobiol. 25:1404–1417. Kato, H., H. Yasui, Y. Yamagichi, J. Aoki, H. Fujita, K. Mori, and M. Negishi. 2000. Small GTPase RhoG is a key regulator for neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7378–7387. Kaziro, Y., H. Itoh, T. Kozasa, M. Nakafuku, and T. Satoh. 1991. Structure and function of signal-transducing GTP-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60:349–400. Kimura, K., T. Tsuji, Y. Takada, T. Miki, and S. Narumiya. 2000. Accumulation of GTP-bound RhoA during cytokinesis and a critical role of ECT2 in this accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17233–17236. Kobayashi, M., S. Nagata, Y. Kita, N. Nakatsu, S. Ihara, K. Kaibuchi, S. Kuroda, M. Ui, H. Iba, H. Konishi, et al. 1997. Expression of a constitutively active phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induces process formation in rat PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16089–16092. Lee, C.H., N.G. Della, C.E. Chew, and D.J. Zack. 1996. Rin, a neuron-specific and calmodulin-binding small G-protein, and Rit define a novel subfamily of Ras proteins. J. Neurosci. 16:6784–6794. Li, Z., L.V. Aelst, and H.T. Cline. 2000. Rho GTPases regulate distinct aspects of dendritic arbor growth in Xenopus central neurons in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 3:217–225. Lim, L., E. Manser, T. Leung, and C. Hall. 1996. Regulation of phosphorylation pathways by p21 GTPases. Eur. J. Biochem. 242:171–185. Lindenbaum, M.H., S. Carbonetto, F. Grosveld, D. Flavell, and W.E. Mushynski. 1988. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional effects of nerve growth factor on expression of the three neurofilament subunits in PC-12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 263:5662–5667. Luo, L. 2000. Rho GTPases in neuronal morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1:173–180. Mark, M.D., Y. Liu, S.T. Wong, T.R. Hinds, and D.R. Storm. 1995. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by EGF and KCl depolarization: a Ca2 independent phenomenon. J. Cell Biol. 130:701–710. Marshall, C.J. 1995. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 80: 179–185. McCormick, F. 1989. ras GTPase Activating protein: signal transmitter and signal terminator. Cell. 56:5–8. Mizushima, S., and S. Nagata. 1990. pEF-BOS, a powerful mammalian expression vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5322. Nakayama, A.Y., M.B. Harms, and L. Luo. 2000. Small GTPases Rac and Rho in the maintenance of dendritic spines and branches in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20:5329–5338. Poser, S., and D.R. Storm. 2001. Role of Ca2 -stimulated adenylyl cyclases in LTP and memory formation. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 19:387–394. Reuther, G.W., and C.J. Der. 2000. The Ras branch of small GTPases: Ras family members don’t fall far from the tree. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:157–165. Rhoads, A.R., and F. Friedberg. 1997. Sequence motifs for calmodulin recognition. FASEB J. 11:331–340. Rusyn, E.V., E.R. Reynolds, H. Shao, T.M. Grana, T.O. Chan, D.A. Andres, and A.D. Cox. 2000. Rit, a non-lipid-modified Ras-related protein, transforms NIH3T3 cells without activating the ERK, JNK, p38 MAPK or PI3K/Akt pathways. Oncogene. 19:4685–4694. Shao, H., K. Kadono-Okuda, B.S. Finlin, and D.A. Andres. 1999. Biochemical characterization of the Ras-related GTPases Rit and Rin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 371:207–219. Spencer, M.L., H. Shao, H.M. Tucker, and D.A. Andres. 2002. Nerve growth factor-dependent activation of the small GTPase Rin. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 17605–17615. Teng, K.K., and L.A. Greene. 1993. Depolarization maintains neurites and priming of PC12 cells after nerve growth factor withdrawal. J. Neurosci. 13: 3124–3135. Vojtek, A.B., and C.J. Der. 1998. Increasing complexity of the Ras signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19925–19928. Wes, P.D., M. Yu, and C. Montell. 1996. RIC, a calmodulin-binding Ras-like GTPase. EMBO J. 15:5839–5848. Wong, S.T., J. Athos, X.A. Figueroa, V.V. Pineda, M.L. Schaefer, C.C. Chavkin, L.J. Muglia, and D.R. Storm. 1999. Calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity is critical for hippocampus-dependent long-term memory and late phase LTP. Neuron. 23:787–798. Zhao, Z.S., E. Manser, X.Q. Chen, C. Chong, T. Leung, and L. Lim. 1998. A conserved negative regulatory region in PAK; inhibition of PAK kinases reveals their morphological roles downstream of Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2153–2163.