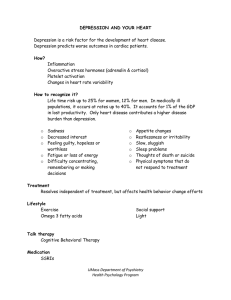

Association Between Depression Severity and

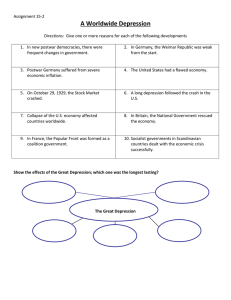

advertisement