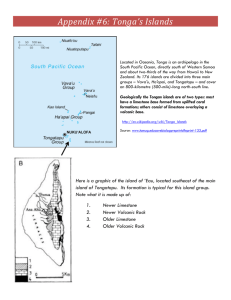

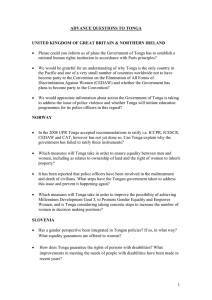

Urbanisation in Tonga: expansion and contraction of political

advertisement