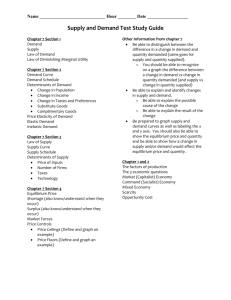

Using Supply and Demand

advertisement