Primary Sources and Editions of Suite Popular Brasileira

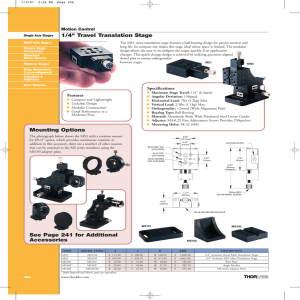

advertisement