Evaluation of Resettlement Programmes in Argentina

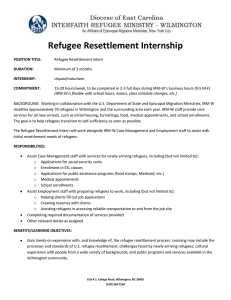

advertisement