Information Requirements in Enterprise Transformations: An

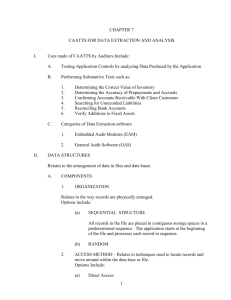

advertisement