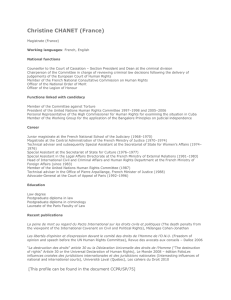

Proceedings - Conseil de l`Europe

advertisement