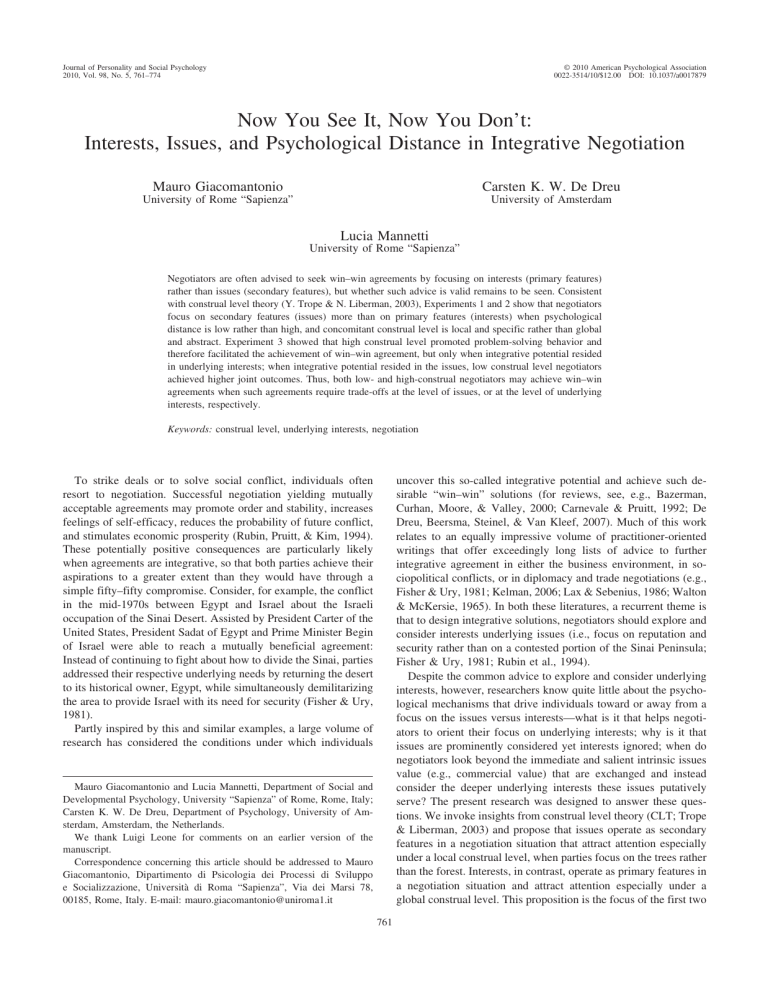

Now You See It, Now You Don`t: Interests, Issues, and Psychological

advertisement