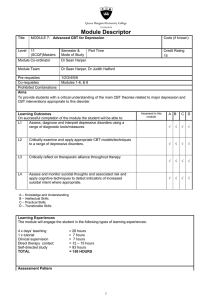

The effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

advertisement