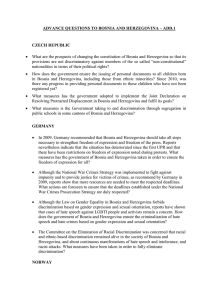

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA - The Internal Displacement

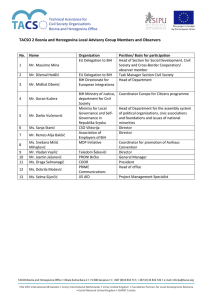

advertisement