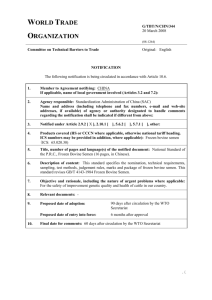

SPECIFIC TRADE CONCERNS

advertisement