inSPire - Lifetouch Yearbooks

advertisement

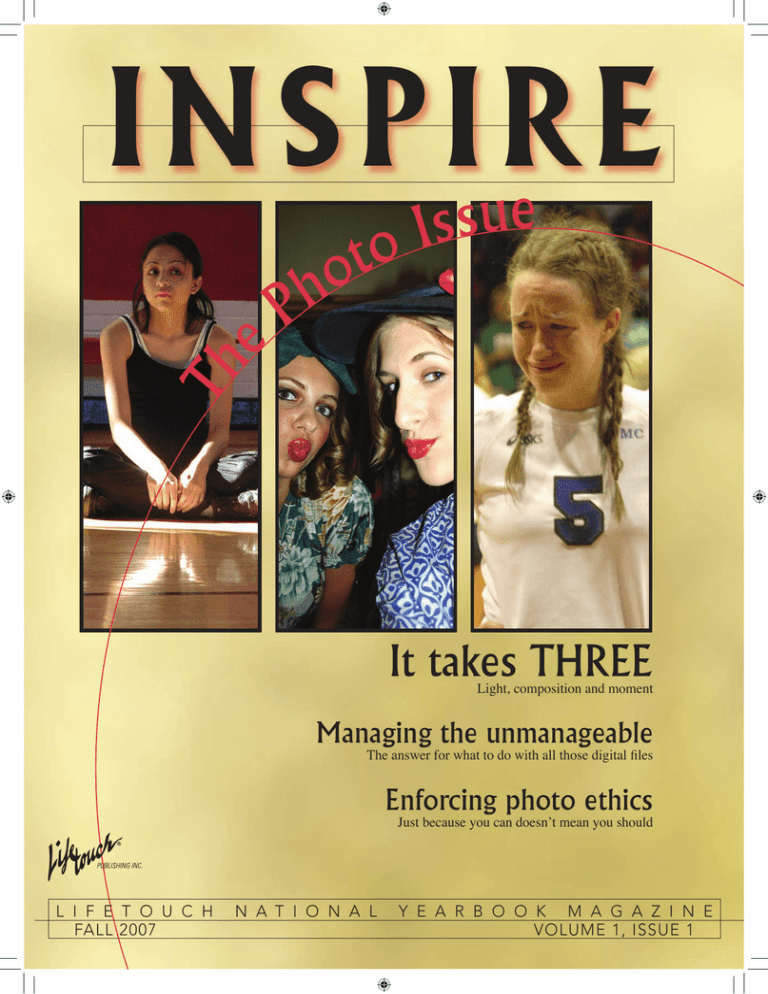

Th inSPire e e o h P u s s I to It takes THREE Light, composition and moment Managing the unmanageable The answer for what to do with all those digital files Enforcing photo ethics Just because you can doesn’t mean you should L I F E T O U C H FALL 2007 N A T I O N A L Y E A R B O O K M A G A Z I N E VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1 VOL_AD_NEWSLETTER 9/17/07 11:36 AM Page 1 Editor in chief She began teaching photography with used film cameras. What a difference a few decades make. JUDY BABB is the Educational and Creative Guru for Lifetouch Publishing. She advised college and high-school publications for more than 30 years. At every level, Babb’s programs have found success as her students garnered top awards in state and national competitions. Book and ad sales soared. Babb was Texas Journalism Teacher of the Year and JEA’s Distinguished Yearbook Adviser. She has CSPA’s Gold Key and NSPA’s Pioneer Award among others. She is co-author of a journalism textbook and created Lifetouch’s innovative curriculum, The Program Works. Editorial board He’s been captured by many a photographer shaking a pica, shaking a pole. H. L. HALL is executive director of the Tennessee High School Press Association after having advised yearbook and newspaper for 39 years. His last 26 years were at Kirkwood High School in Kirkwood, Mo, where his staffs won every state and national award. He is recipient of the Dow Jones Newspaper Adviser of the Year Award, JEA’s Yearbook Adviser of the Year Award, JEA’s Carl Towley Award, CSPA’s Gold Key Award, JEA’s Teacher Inspiration Award and NSPA’s Pioneer Award. He is the author of NSPA’s Yearbook Guidebook and two textbooks. DEB LEE is an 18-year adviser at Hudson High School in Hudson, Wis., where she teaches business and advises the yearbook. Lee has served as president and vice president of the Chippewa Valley Student Press Association and makes it her mission to learn about creating a solid, interesting publication. Lee received CVSPA Adviser of the Year Award. Lee’s staffs have won state and national awards. Her staffs have won CSPA Gold Merit Awards with Columbian Honors and NSPA All American Awards with Marks of Distinction. To compete against other, larger programs, TERRY NELSON’s staffs emphasized great photography and won. Thirty years later, they still do. Terry is a 31-year veteran of teaching journalism and advising publications. Currently at Muncie Central High School in Muncie, Ind, the Munsonian newspapers and Magician yearbooks have been named NSPA All-Americans and Pacemakers and CSPA’s Gold and Silver Crown recipients. Nelson was Dow Jones National Journalism Teacher of the Year and was a member of the USA All-Teacher, First Team in 2000. She has won CSPA’s Gold Key and NSPA’s Pioneer Award. She has served on the boards of JEA, CSPAA and the Student Press Law Center. John Haley Scott teaches visual media at Thomas Downey HS (Modesto, Calif.) and graphic design at Modesto Junior College. He advises the Knights Herald newspaper, Shield yearbook, and co-advises the interactive yearbook at Downey. He is a graduate of the Military Photojournalism Program at Syracuse University and has worked or taught in the photojournalism field for 31 years. His students have won nine NSPA\NPPA Pictures of the Year, two NSPA\Adobe Design of the Year awards, more than 30 CSPA Gold Circle awards, the Gold Crown for both newspaper and yearbook, the Pacemaker for yearbook and the Pacemaker for interactive yearbook. Howard Spanogle, copy editor for Communication: Journalism Education Today, has been thinking high-school journalism for four decades. He began advising in North Carolina; then moved to Glenbard East (Lombard, Ill.) and Highland Park (Dallas, Texas). In addition to awards for him and his students, his book credentials include Teenagers Themselves Trilogy, three studentwritten books for a New York publisher. He is an experienced judge, program coordinator, editor, including Lifetouch journalism textbooks. Bernadette Tucker has naturally poor vision, and a recent single-car accident gave her permanent “floaties.” Bernadette says it forces her to take a closer look at a lot of things in life, and that’s actually an advantage. The advisorial eye is not housed in the optic nerves. Take a closer look at Tucker’s way of seeing things. She’s dealt with her fair share of student press law and ethics issues while advising Pacemaker and Best of Show newsmagazines at two California schools. Now at Rancho Cotate High School in Rohnert Park, Calif., she has just finished her first yearbook and will coach both publications. Expect the unexpected Judy Babb That’s what Inspire is all about When Lifetouch set about to create its own magazine, the first question asked and answered was what do we want to accomplish. Hence came the name Inspire. We didn’t want to create another me-too publication that readers flipped through when finished with one project and then plunged onto an ever-growing stack of papers. No, ours would be a must-have and a must-keep and would be timed to help with the must-do’s an adviser faces on a daily basis. We plan to do that with this start-back-to-school s issue appropriately fixed on the part of yearbooking that consumes us all the most: photography. That brought us to our second question: Who should be involved in the inspiration? Reading the bios to the left and the stories that follow this introduction shows our dedication to inspiration. More than 150 years of advising combine to create a plethora of ideas, experiences (and we’ll all admit good and bad) and challenges. Involvement in state and national scholastics provides the group with literally thousands of other experts we can tap to help create the lifeblood of the publication. Look to Inspire to get you to think of photography in its most essential elements—light, composition and moment. And look to the expert to help you see those things clearly as John Scott introduces digital asset management using Adobe Bridge. H.L. Hall will teach the essense of composition while Terry Nelson provides the know-how on capturing the moment. And there’s more. Bernadette Tucker will also provide that all-important look at photo ethics: what can we do and not do. And we’re planning to offer far more than the print media allows. We won’t be limited by page numbers as we make downloadable forms and the means to engage your staffs to create the best possible yearbook they are capable and desirous of producing. Look for our five-minute lesson on color-balancing that will change the entire look of your yearbook. Simply go to yearbooks.lifetouch.com to find John Scott’s quick method to color correction. But this issue and the ones that follow will offer you far more than the quick fix although we need as many of those as we can find. It will also provide you with what we hope will inspire, then engage and finally create the experience we all want our students to emerge from our classrooms with. We will look to the lifeblood of great publications—the adviser. We will also address how to get past adviser burnout and turnover, help you to create content-driven yearbooks as we provide life essentials that make being a part of your staff a must-have for the best and the brightest, for the most creative and the most needed. LT Colophon The design for this issue of Inspire is loosely based on Collection IX from the Designers Cut in the Lifetouch Volumes Template Book. Desiring to show you how your own touches can make these solidly and creatively designed sets of templates your own, a circle shape became part of the design elements. Fonts used in the magazine are Flare Serif, one of Lifetouch’s new font offerings. Avenir is used as the sans serif for sidebars and captions. Times is used for subheads and body copy. Inspire procESS A smooth workflow guarantees ease when placing photographs on pages controlling the using a digital workflow By JoHN Haley scoTT At the turn of the century, my students were making 6,000 to 7,000 scans from color negatives each year in the production of the yearbook. Remarkably no image or negative was ever lost. Yes. No image or negative was lost. And there were eight different students scanning and working the images throughout the day. How? It was easy. We developed a system that was uniform, practical and easy to understand. When we moved to complete digital capture in 2001, we adapted that process and continue to refine it as software updates offer better tools. Today the workflow we use at Thomas Downey High School is similar to those spelled out in recent articles about Digital Asset Management (DAM). I think it’s cool that someone came up with a fancy name for what we have been doing with our files for nine years. I love the chaos associated with the creative process, but lost or misplaced design assets easily angers me. I am also lazy so I want to be able to quickly locate anything — and I also want to know info about the file without opening it. A standardized file naming structure allows all that and more. Simply by reading the file name, we know the content, date taken, photographer, number of images in the sequence and status of the file in our workflow. Key metadata information is also viewable without opening the file when using Mac’s Spotlight or details view in Windows Vista. A typical file name in our workflow or DAM system would look like this: VB_071101_CH_001.JPG. VB is the event (varsity volleyball); 071101 is the date taken (year, month, day); CH is the photographer’s initials; 001 is the frame number; and JPG is the file type (in our workflow jpg files are ready for print — they have been converted to CMYK, color corrected and set to the correct resolution for publication). If the file is black and white, it is saved as a TIF. All native or unaltered original files are saved as PSD or NEF files depending on their capture method. Any file that enters our workflow is first uploaded to an archived location in the “Untouchable Zone,” an area of our file server where the original files are stored. If the files are from a digital camera, they are uploaded to a folder that is labeled by event within the photographer’s RAW folder. Using Adobe’s Bridge software, the uploaded files are first culled for duds (empty frames, out of focus, or incorrect exposures) and then renamed using the standardized naming structure. General caption information and keywords that can be associated with all the files in this collection are entered and saved using the FILE INFO command in Bridge. Later more specific information is added to individual images. Bridge records anything that is entered into the fields within the FILE INFO dialogue box for future use. Previous entries appear when clicking on the triangle tab to the right of each field. Computers store this information locally, and it is advisable for students to use the same computer whenever possible to get the most of this feature. Once the general caption information is entered, files are edited more critically. Final selections are processed for page placement using PhotoShop and saved as JPGs in the spread folders. By following this process, the original files are never altered and can be located easily because the file extension is the only part of the file name that is changed in the workflow. The secondary benefit to captioning in Bridge comes into play within InDesign. Any information entered in the FILE INFO can be acquired from a PLACED image using the LINK FILE INFO… selection under the triangle tab of the LINK palette. The same FILE INFO window that appeared in PhotoShop will open, and any information can be copied from there and pasted onto the InDesign page. I recommend that students write a complete caption, one that is fit for use, in the publication’s style in the DESCRIPTION area of the FILE INFO during the editing process. If the photo credits are included as the last line of the caption, ALL the information about an image can be put on the page in one action. At Thomas Downey, we use a simpler process for images scanned for advertising. A folder is created for each advertiser, and the size of the ad is included in the folder name. Knowing the size of the ad allows page designers to shuffle the ads by size before copying them into the spread folders. Any ad scan includes the advertiser’s name and position number as it is associated to the dummy design to guarantee the client’s instructions are followed. This workflow has served my students well and has kept me relatively sane for years. I don’t pretend to be an expert at using the process. In fact, it is my students who make everything work — I simply strive to remove variables and to enforce the routine, which is what guarantees a smooth operation for each design and for each deadline. LT • Study staff training information sheet on page 6. Screen shots of the digital asset workflow illustrate the ease and the efficiency of this process. • Laminate copies to use in the yearbook lab. Inspire 5 L cUll YoUr dUdS • Use a Single Star Rating in Bridge to label empty frames, out of focus or grossly exposed images. Then sort by ranking and delete. This process saves space. to BAtch rEnAME • Use a standardized nam- ing structure for all your digital files — and stick to it. Make sure to include the event, date, photographer’s initials. After the files have been renamed, use a Five Star Rating to edit images for publication. Then sort by rating and copy them to the desired location (spread folder) and prepare the files accordingly. linkEd info • Click on any image placed in an InDesign document while the LINKS palette is open, and its name will appear highlighted. Click the highlight, select LINKED FILE INFO... from the Options Tab (the triangle in the circle). That window will open. cAption iMAgES • Enter complete caption in- formation in Bridge using the FILE INFO... under the FILE MENU. This information will stay in the file and can be retrieved by a number of applications. A general caption can be applied to a selected collection of images by selecting them at the same time and then opening the FILE INFO palette. copY And pAStE • Once the LINKED FILE INFORMATION window opens, highlight the caption in the Description and paste into a text frame. Format the caption accordingly and continue to work more efficiently. Light: Turn readers’ eyes to the school canvas Photographers cannot create light in the world, but they can control how and often when the light shines on the world they are photographing. They can empower their lenses to open new views to yearbook readers. By JoHN Haley scoTT Photography is an art and a science. And there is an inherent process for capture, evaluation and output that fall neatly into three categories: Light, Composition and Moment. Photo instructors are quick to make the distinction between photography and painting. The common quip, “Dumb like a painter,” is often used to demark the differences. Painters can create their own light. Photographers are limited by the physical properties of light and by the electromechanical sophistication of their capturing device: the camera. The camera works only when there is light. A painter’s brush has an unlimited palette. The camera can capture only the light that is available while the brush needs only painter’s imagination. To capture an image, the first hurdle in the process is light. In these days of automatic everything, the camera — or better yet the photographer — makes a decision regarding exposure. Either decision maker has to balance shutter speed with aperture (lens openings or f/stops) within a selected ISO (sensitivity to light) to ensure a correct exposure. Shutter speeds and apertures are the A and B of the exposure equation because one has to balance the other. Consider the possibilities. 1. Faster shutter speeds stop more action. 2. Large lens openings shorten focus. 3. Small lens openings increase depth of field or lengthen focus. Inspire 7 But a camera can stop all the action and have everything in focus only in bright sunlight or in a room that is equipped with multiple flashes because the quantity of light is the ISO part of the formula. Even with high ISOs the amount of available light is the limiting factor. Mastering exposure settings is essential to making quality images. Libraries are filled with books about the subject, and every wellwritten photo textbook contains chapters that address exposure equivalents as they relate to stopping action and depth of field. Advisers, photographers, editors and designers need to take advantage of helpful resources on their way to mastering exposure settings. Every image starts with a choice. In the capture process, photographers have to consider the lighting of the setting and its limitations. If they want everything in focus, a smaller lens opening will require a slow shutter speed. However, the slower shutter speed will stop less action. If the room is too dark and they want to stop action, the faster shutter speed will require a larger lens opening that in turn shortens focus or depth of field. In most cases, stopping action is the primary consideration. Light makes pictures. Knowing its characteristics is the key to making images that are rich in hue, have a full range of contrast and truly capture the mood of a moment. Images captured at high noon have short, harsh, unattractive shadows. Eyes squint to hold back the brightness, and the contrast is sharp and unflattering. Images captured in the hours after sunrise and before sunset have long, attractive shadows. Eyes open to drink in the warm hues, and its contrast is long-toned and sensual. The light from the north is diffused and even toned. Open shade provides rich, subtle light that has even tones and pleasing contrast. Window light, depending on the time of day, will provide a diffused version of the light outside. Cloudy, overcast days have light that is flat, short toned, with limited contrast and less vibrant hues. Yearbook advisers recognize that great images are no accident. And they need to train photographers and all staff members to think the same way. Remind them that accomplished photographers make mental or physical notes about the light of particular settings long before an image is ever captured. To make students true believers, share tips from landmark professionals such as the following: • During a presentation at Syracuse University, Hiro, a famous New York fashion photographer, said, “I never stop looking for pictures. I even wash my hair with baby shampoo so I can keep my eyes open in the shower.” • French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson coined the term, “The Decisive Moment,” to describe the relationship of setting, content and the moment of peak action in which all the elements are in perfect order. His technique is simple: Find the setting and wait. Repeat this lesson frequently — always with enthusiasm. The wonderful part is that every aspiring photographer, whether a novice or an advanced photojournalist, can achieve this goal. Capturing images in a school setting is relatively simple. Most rooms have similar lighting, predictable interactions, dozens of opportunities and ample subject matter. However, photographers must takes note of where the light is and when it is best for making images. HOW TO SHINE LIGHT Say no to gray and yes to light and life in yearbook photographs. Use these tested techniques: • Highlight exposures, always critical, to ensure that there is information (data) in the whites because detail is data dependent. • Standardize and strictly practice color correction or adjustment. • Learn how camera controls affect exposure. • Consider purchasing noise removal utilities so noise is less annoying when capturing action at ISOs above 800. • Be aware of bright objects in the background because cameras typically expose for those objects and under expose the foreground as a result. • Experiment with flash equipment, and learn how to use it to reinforce existing light. • Capture often, capture more than one image and capture from a variety of angles. • Keep the camera between the light source and the subject to ensure the subject is lit. Every school has a long hallway with beautiful leading lines that become dramatic when the light is right. There are at least a dozen sports that have contests in the hours before sunset when the subjects are lighted from the side, at times rim light, with brilliant, spectacular highlights. Advisers want photographers and editors to think about what they see daily. Skilled teachers usually have more success if they require students to create a visual opportunity notebook or visual coverage map as the first step toward being in the right place at the right time. Photographers must learn to scout their surroundings. They should examine how things look at different times of the day. Then they can capitalize on when the light is right and develop a plan for handling situations when conditions are problematic. In addition, advisers and editors need to establish a visual vocabulary for discussing light and how it affects the capture process as well as how it plays in the evaluation of images to be used in print. The power of color in an image amplifies its ability to convey the mood of an event or subject. But the wrong color, especially on someone’s clothing or in the background, can also destroy the mood and hence make the photo less usable or powerful. There are times in the design process for using images with extreme contrast. It is essential for photographers, editors, designers and writers to know how their use of images will impact the readers’ perceptions of the visual content. A subtle, somber story about a student recovering from a serious illness will not meet readers’ expectations if the subject’s picture is taken under the harsh lighting of the noontime sun. As photographers think more frequently about light and view the world around them in terms of light, they will take giant leaps toward producing a yearbook filled with truly great images. While the images will demonstrate the photographers’ mastery of the light available and the editors’ decisions about good shots and high standards, the big winners will be yearbook readers as they benefit from the light on their world. LT Inspire photo composition: it’s an art form Anyone can learn basic skills that result in stellar photos BY H. L. HALL Runners and dancers need feet, but not everyone needs an entire head or all parts of their arms. Even if they have entire heads, ceiling lights, trees, poles or bushes do not need to grow from them. When it comes to composing subjects in a photograph, photographers normally should get in close, but sometimes they can get too close. Cross country runners generally need both feet in the picture. The same is true for dancers. Both runners and dancers look strange moving on stubs. That’s true of anyone in a photo. If it’s impossible to crop a photograph to leave in the feet, then it’s best to crop at the waists of subjects rather than showing them standing on stubs. At the same time, it’s not always necessary to leave in the top of COMPOSITION RULES Ruthless cropping, framing, leading lines, rule of thirds and varying the camera angle make these simple photos shine. And, of course, the rule of KISS — keep it simple stupid — keeps each from becoming cluttered, having a simple subject and does away with distractions. Use these principles and your photos will have the excitement you want them to have. someone’s head or both ears. Ruthless or tight cropping can actually make a photo stronger. A good guideline is to crop within two picas of the center of interest unless the subject is moving and the viewer needs to see the area the subject is moving into. Photographers should also be aware of unsightly mergers. Sometimes it’s best if photographers stand on a chair or table or ladder to shoot down or to avoid the illusion that ceiling lights are growing out of people’s heads. In addition, photographers also need to be aware of background mergers when composing a photo. Unsightly mergers create clutter that detracts from the center of attention. Although it is possible to get too close, photographers will probably get better pictures when they get close. “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” said Robert Capa, a former photographer for “Life” magazine. Capa became known for shooting war photographs during World War II. Capa landed on Omaha Beach June 6, 1944 (D-Day) with American soldiers. In his book, “Slightly Out of Focus,” Capa describes his “up-close” experience. “The water was cold,” Capa said, “and the beach was still more than 100 yards away. The bullets tore holes in the water around me, and I made for the nearest steel obstacle. A soldier got there at the same time, and for a few minutes we shared its cover. He took the waterproofing off his rifle and began to shoot without much aiming at the smoke-hidden beach. The sound of his rifle gave him enough courage to move forward, and he left the obstacle to me. It was a foot larger now, and I felt safe enough to take pictures of the other guys hiding just like I was.” Capa got in close to the action, and that’s what all photographers need to do. Don’t stand on your team’s sideline when shooting football pictures if the action is on the other side of the field. Zoom lenses help, but you can’t get that up-close feeling without being up close. In 1954, “Life” sent Capa to the Indochina front to take more war pictures. Again, he got in close to the action, but this time he was a little too close. American troops found his body. He was still holding his camera. Because Capa believed in getting in close, he took his camera farther into the fighting zone than any photographer before him. He had a knack for recognizing the peak of action, and he realized the importance of getting close. ‘If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.’ — Robert Capa All photographers, when composing a photograph, need to keep Capa’s words in mind. Don’t shoot a sea of faces in a crowd at a sporting event. Get in close on two or three fans who are cheering wildly. Don’t shoot the entire band marching onto the field. Get in close on two or three band members with great facial expressions that show the physical exertion needed for the performance. Don’t shoot the entire a cappella chorus singing at a concert. Get in close and show two or three members who are singing with gusto. Don’t show all the basketball players lined up along the free throw line. Get in close and capture the expression on the shooter’s face. Photographers need to remember to play on the viewer’s emotions when composing a photograph. Be sure each photograph is an attention-grabber that delivers a message. The best photograph does not need a caption. The viewer should be able to tell what’s happening simply by looking at the picture. Getting in close, capturing great facial expressions and good cropping are keys to strong photo composition. There are, however, other techniques photographers may use to strengthen their pictures even more. • rule of Thirds In the viewfinder, mentally divide the image into three vertical and three horizontal areas, like tic-tac-toe. Place the center of interest at one of the four divisional points of the board. By using the rule of thirds, the main subject of the photo is off-center and balances the weight with other objects. This is generally more effective than placing the main center of interest directly in the middle of the photograph. • angle Don’t always shoot straight on. Sometimes the best angles come from above or below the center of interest. If your basketball gym has a balcony area, try shooting down on the action. Lie on the floor to shoot a wrestling meet. As already mentioned, to keep ceiling lights from protruding out of people’s heads, stand on a chair or a table in a classroom. Also think of moving to the side rather than shooting straight on at people. Think of the image as you would a clock. If the subject is at straight-up noon, move to 4 p.m. or 8 p.m. to shoot to avoid flat one-dimensional photos. “The best lens God ever gave you was your own two feet,” Douglas Kirkland, famed Look photographer, said. • Framing To frame a photograph, find some object in the foreground that leads the viewer into the picture. For example, a doorway might frame a science lab or some other interesting classroom activity. Frames don’t have to form four sides nor do they have to be rectangular. Shooting through a fork of a tree or under the extended arm of someone can also be frames. The reality is framing exists almost everywhere — a fan standing on the sidelines to a teacher standing over a student at a desk and framing can usually improve a picture. The frame does not have to be focused, as the frame should not be a distraction to the viewer. • leading lines Leading lines can help guide the viewer to the center of interest. For example, a fence might lead the viewer to a horseback rider, or one line of the marching band might guide the viewer to the drum majorette. Use of leading lines can add impact to the center of interest. • kIss—keep It simple stupid As already mentioned, keep the backgrounds uncluttered and create a strong center of interest by keeping the subject(s) in focus. If there is something distracting in the background, change your position. Sometimes, you can simply change the way you’re holding the camera. It’s logical to hold it horizontal, but move it vertically, and you’ll capture a totally different image. The reality is when you fill the frame, more photos will be better taken vertically than horizontally. There is no one “right way” to compose a photograph. Simply be sure you are presenting the message you are trying to deliver. If you have the correct lighting, the correct focus and the correct cropping, you should have an effective photo. Compose pictures that get attention and deliver your message. In general, good pictures result from careful attention to the basic elements of composition, together with appropriate lighting and an interesting subject. There is, however, no “right” way to take a picture. Three photographers recording the same scene may create equally appealing photographs with entirely different composition. As a photographer, if you can truly say the photograph you took is delivering the message you wanted to present, then you have succeeded. Chances are you will deliver that message best when you get in close. LT Inspire 11 moment: a split second captures all 1 PANNING Using a slow shutter speed and moving the camera with the action stops the movement of the running back while his faster moving blockers are blurred. This kind of photograph comes from planning and multiple attempts to get just the right shot. 2 Occasionally it is luck, but great photography comes from following a consistent plan and waiting for something to happen 1 2 HIP HIP HOORAY Celebratory moments like this can be captured only by thinking ahead, waiting and being ready. This photographer obviously thought ahead and moved into position as the senior team realized they had locked up the all-class competition. GREEN SLIMED Finding out the plan and then following the action allowed this photographer to get the moment when the queen was crowned. By Terry Nelson Seventeen-year-old Jordin Sparks had hers at the season finale of American Idol. Colts quarterback Peyton Manning had his in Super Bowl XLI. Former vice president Al Gore’s may have been at this year’s Academy Awards. And my mother’s most certainly had to be the birth of me. And you can have it too. This Magic Moment. A fraction of a second in time, frozen for media audiences to witness, respond to and remember. Throughout history, photographic moments have brought back images and remembrances of noteworthy events. • Little John-John Kennedy solemnly salutes the flag-draped casket of his father and U.S. President as the funeral parade winds through the streets of Washington, D.C. in 1963. • A little girl, Kim Phuc, runs naked down a street in South Vietnam as she flees a Napalm attack that burns her skin, her eyes and her limbs in 1972. • The weary fire department captain carries an infant from the wreckage of a federal government building in the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995. • The second plane hits the New York City World Trade Center in an unbelievable image that is published around the world on Sept. 11, 2001. A single photograph. One-eighth of a second in time can equal a lifelong memory. The reaction of your injured starting basketball player on the bench at the moment he realizes the team has defeated their biggest rival for the sectional title. The laughter that erupts when two longtime friends share a table and a tale at lunch. The clenched raised fist of victory brought swiftly down into the body when an academic team member nails the answer in the Renaissance category at the state meet. One moment in time. Preserved in a book that is never going to be thrown away — your yearbook. Taking photographs for student publications is never an easy task. Hundreds of activities and events occur each month for the school’s 25 athletic teams, numerous music, art and performance groups, academic and public speaking competitions, play productions — and that’s merely AFTER school. During school, group projects, dissection labs, term paper research, guest speakers and field trips gobble up a day of picture-worthy events for the curious, persistent photojournalist who carries her camera with her as a third appendage waiting for the right moment when she sees the reaction, the movement, the surprise, the stolen looks. Becoming an accomplished student photojournalist takes more than an expensive camera and some blind luck, however. Catching the right moment takes comprehensive study and planning. So let’s get down to business. I see it as a six-pronged attack, which you can repeatedly emphasize for your students. strategy 1: know your subject. Photojournalists who are looking for a single picture to tell the story must first know about the event before they lift their cameras. How? By looking at past issues of the school and local newspaper — what images have already been published? By taking a look at last year’s yearbook and the one before that. How have events such as Homecoming or football or cross country or Key Club been covered in the past? Find out who the resources are. Talk to the coach, the sponsor, the student float designer, the good friend. Chances are they will help you identify all sorts of moments when a great storytelling picture might be taken. A Texas adviser tells the story of a girl who was waiting for the announcement of Homecoming Queen. Obviously any girl would be thrilled to be awarded this title. But one particular girl is the picture — whether she wins or loses. Each of her five older sisters was named Homecoming Queen. For this youngest girl, not being named queen would be devastating. What a wonderful story. Now all the photographer has to do is focus on this candidate and record her reaction: good or bad. strategy 2: Work with others. Photographers should work on “previsualization” before covering an assigned event. The technique involves a group of students collaborating on potential story-telling moments. The brainstorming can help avoid track spreads that look the same: the hurdler from the side clearing the bars or the runners crossing the finish line. Before photographers go out to shoot the same old worn-out angles and moments, they should take a few minutes to brainstorm with the assigning sports editor or reporters for possible moments or fresh angles from which they can photograph. How about, at practice, lying on the ground as pole-vaulters travel over them? How about panning the camera with the hurdler to blur out the background and freeze the action of the athlete? What about shooting a race at an angle that includes the timekeeper who watches the line as the winner crosses it? What about a photograph from behind the last runner in the race? All photographers need help to imagine additional scenarios and angles. They need to brainstorm and plan for shots before the action happens. One of the best photographs ever taken by a staff member of the play did not happen on stage but behind stage right before a student was to make her entrance, when she stepped on the hem of a long dress and ripped it away from a waistband. The photograph was of six costume girls gathered around this actor, frantically fanning herself while they made the quick repairs to reattach her skirt moments before her entrance. And how about the photograph of the drama students snowmobiling into school and carting along a chainsaw one Saturday afternoon to build the set. That, too, is part of the story of producing a play. strategy 3: Be familiar with your equipment. News-breaking moments are not going to wait. That means photographers must be sure their battery works, their card has space and the camera release button is not on lock. Although most digital cameras are fairly fool proof, the serious photojournalist has a much better chance of getting a compelling shot if she knows how to set certain depths of field that highlight the center of interest or is able to freeze or blur action for effect. If photographers do not have a camera manual for their equipment, they can download a booklet or visit their local camera shop. Of course, they have to read it. Another strategy would be to shadow a professional Lifetouch photographer and pick up diverse tips from the pro. strategy 4: Choose an interesting subject. A photographer has an entire game to cover, but he needs one great shot. Sure, he could shoot continuous frames, then edit all night long. But a better approach might be to watch the game, find the most expressive participants or the ones who are the muddiest, most accident prone or interactive. Check out the crowd. Are there boys with body paint and wigs. Are there girls wrapped in blankets and huddled under umbrellas? Look at the colors. Because more yearbooks are publishing all-color yearbooks, color becomes an important component of composition. Schools often have 500 to 2,000 or more students to photograph. Photographers must choose an interesting looking subject — either for dress and color or for stance and mannerisms. strategy 5: Move in close. I know, I know, photographers may have a little zoom. Big whoop. But if they hang around long enough so that the subjects are no longer grinning for the camera, posing for a yearbook “candid” or watching where the lens is pointed instead of the action on the field, eventually the subjects are going to get bored and turn their attention to the game. Now photographers can take the picture from a fairly close range as they fill the frame with a great facial expression or compelling reaction. The closer they get, the less dead space they need to edit out and the bigger the enlargement without pixelation they can achieve for their yearbook design. Edit off those silly posed shots or better yet, shoot away without the card. Eventually the jokers will tire of posing and return to being real — even with the photographer in close range. strategy 6: Wait for something to happen. How appealing are yearbook photographs of a student sitting at a desk to look at a book? Ugh. How inviting are photographs of a basketball armpit shot? P.U. Of a girl in the hallway talking to friends, looking at the camera? Blah. No book needs 300 pictures of math class — simply the one when a student answers the question incorrectly, smacks his face with his hand, all embarrassed, while his classmates giggle at the situation. Or the editor needs the photo of a student who needed a passing grade to earn credit for the class. Then, when the tests are returned, she realizes that her scores are high enough to give her that D she needed. Her expression, while not broad, will surely show her relief. What about that basketball coach who takes his 2-year-old toddler up the ladder with him to cut the net at sectionals? Or the students on the float who get pelted with candy the crowd throws? The moments are there. Alert photographers look and wait for them. One additional note: The reaction to the event is often the best story-telling moment to photograph. I’m not saying don’t record the game, but more often than not the reaction to the score of a close game is a better news moment than the action of the game itself. How many out-of-focus tackle shots do editors really need in the yearbook? Although high-school photographers are all too young to remember the musical group, Jay and the Americans, I can’t help but hum the opening lyrics of their songs, aptly titled, “This Magic Moment.” “... so different and so new, was like any other...” For editors and photographers, the lyrics translate to pragmatic advice: Help your yearbook sing out the moments of an incredible school year, jam-packed with all sorts of characters, situations and surprises in the pages of the 2008 edition. Be part of the photo team that sears the images of a year at your school into the memories of a lifetime. Being informed, knowledgeable, creative photojournalists who know their cameras, you become a valuable addition to this year’s staff. Grab the moment. Make it yours. Make it ours. LT Inspire 13 Ethics: It’s a slippery slope It’s so easy. It’s so hard. Photoshop lets you do it. Can it be wrong? Of course, the answer is ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ Create a cut-out object. No problem. Cut out something you don’t like in the background and that’s another story. You’ve changed reality. By Bernadette R. Tucker If I am caught in a lie to the whole world, I hope I handle it as Brian Walski did. While covering the Iraq War in 2003, he captured a series of images of U.S. forces with Basra locals. He wanted to show the face of a soldier communicating with an Iraqi holding a child, but the only way to do that was to create a composite. He took complete responsibility for what he did, acknowledging the truth when asked by his editor. He did not make excuses to interviewers even though his colleagues and competitors did. They pointed out that he made the image at the end of a 14-hour workday, when he had not eaten or slept in 36 hours of filthy, dangerous field coverage. The Los Angeles Times fired him. Now, he runs his own freelance business in Denver, a far different life from his award-winning days covering national and international events. He did not get the second chance that Patrick Schneider did. Another audacious photojournalist, Schneider covered all sorts of local fires, disasters and other events for the Charlotte Observer. He won top prizes every year in regional contests and was a contributor to a Pulitzer Prize-winning package on Hurricane Katrina. But he used Photoshop to alter the color and background of some of his images in such a way that his editors had to issue an apology to readers and to suspend him for three days in August 2003. Officials at the North Carolina Press Photographers Association quickly rescinded three of his awards because his contest entries had been changed as well. Shortly thereafter he told a crowd at the Women in Photography conference in Charlotte that he had gone “too far” in burning some of the photos. At the time, he was admired for exhibiting the raw images alongside the adjusted, published ones and for encouraging discussions about the ethics of using software to makes changes in spot news photos. But then he did it again in 2006. He altered the colors in an image of firefighters. It was eerily similar to one of the controversial photos from 2003. After being fired, he is now running his own photographic business in Charlotte. Why couldn’t he stop himself? It is a slippery slope. Instead of enhancing contrast and brightness, Schneider moved beyond simple color corrections into creating the image he desired rather than honoring the one he had captured on his camera. Even Walski, who never publicly violated ethics standards again after his dismissal from the LA Times, said that he had “tweaked” photos by eliminating distracting elements such as a telephone pole before the Iraq War incident. If professional photojournalists are tempted by the power of the software, it is no wonder that our students are, too. That is why advisers have to help them set — and make them adhere to — ethical standards such as the ones followed by editors of the Times and the Observer. Be clear about the intended use of the photograph. It is appropriate for an Adobe Photoshop-friendly A PHOTOSHOP NO-NO One can’t help but prefer the image without the girl with the cell phone, but she’s there and she should stay there. Many professional photographers have lost jobs and credibility by removing something — or by adding something to a photo that wasn’t originally there. The solution: “Just don’t do it.” BACKGROUND from professional organizations http://www.poynter.org/resource/28082/LATimes.pdf pdf of the front page with Walski’s image on it http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpsrv/photo/essays/vanRiper/030409. htm all three of Walski’s images in one article, without flash process http://www.poynter.org/content/resource_popup_view.asp?id=20120 http://www.zonezero.com/editorial/octubre03/october.html side-by-side comparisons of Schneider’s rescinded award winners from 2003 http://www.pdnonline.com/pdn/newswire/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002914629 altered image of Schneider’s from 2006 http://www.newsdesigner.com/archives/002578.php shows page on which Schneider’s 2006 photo appeared You may also wish to check additional sources: http://www.nppa.org/professional_development/business_practices/ethics.html Complete guidelines of the National Press Photographers Association • New York Times Photo Policy • Charlotte Observer Photo Correction/Editing Guidelines Both as posted on www.poynter.org by Terry Irby on Sept. 5, 2003 staffer to go hog wild on images designed as art. But it must be absolutely clear that those are photo illustrations. Those are common, and perfectly acceptable, on covers, divider pages, backgrounds and on special feature coverage. Students can create collages or manipulate an image using layers, filters and color alterations of any kind in those circumstances. However, images of specific moments in time — typically in classrooms or at sporting events — are called spot news photos. Those may not be created through computer manipulation. Photographers capture them by being in the right place, at the right time, with the right equipment. It is misleading to “enhance” a varsity football photo by erasing someone’s distracting hand. If the girls junior varsity basketball team action shot does not include the ball, it is not appropriate to swipe one from another image and put it into the one that is going on the page. It does not matter how ridiculous the homecoming queen’s face is in the photo of the big announcement. It is not ethical to adjust her hair, move the crown just a bit or replace her expression with one from a different shot in the series. Be conscientious about how the photos are acquired. Basically, if your students did not snap the shutter button or sketch the image, you do not own the image and you do not have the right to use it. No matter how easy it is to scan a magazine or book or to surf the Internet for any image — whether it is clip art or a photograph — it is illegal to copy and paste those into page designs. Even if a copyright mark is not visible on the website, those are owned by someone else. You must obtain written permission to use them. Even an e-mailed release form from the copyright owner would suffice. Besides being illegal, that approach is lazy. There are other ways to come up with the necessary equivalent: 1. Take the photo. Honestly, this is the best choice. If the page focuses on favorite bands, take a photo of a stack of CDs. When the story on fan obsession requires something that shows Avril Lavigne, create a portrait of the student surrounded by memorabilia of the singer. 2. Buy them. Purchase a CD of stock images, pay for individual photos from Getty or Associated Press or subscribe to an archival service such as MCT Campus, which has thousands of current news and pop culture event images. 3. Include the Lifetouch mini-mag, A Year in the Life, in the yearbook. It will feature the celebrities, fashion and key news events from the year. As advisers, we must be mindful of why we are teaching. It is not our job simply to help our students publish the book. That is merely the end result of what we do. The process we go through in developing that publication is far more important. Our priority should be teaching our students the legal, ethical way to produce it. And make no mistake, that part is truly up to you. Without you, they do not understand why taking someone’s photo off MySpace to use as a candid is incorrect. In their private lives, they do such things all the time for their own amusement. They need you to educate them about how to make decisions about when something is legal or ethical. Be proactive about potential problems. After you teach relevant cases and laws, you should review your editorial policy and code of ethics with your staff. If your publication does not have one, that should also be at the top of your agenda this year. You do not have to write them from scratch. The Journalism Education Association Student Press Rights Commission, at jeapressrights.org, offers policy and ethics code models as well as a variety of valuable teaching materials. Lifetouch’s own The Program Works goes through ethics and responsibility and helps you create a policy that would ensure that students know what they can and cannot do. It is vitally important that you and your staff decide what you will or won’t do before you get close to deadline. If you know the law and have the policies in place that ensure thoughtful, ethical decisionmaking, then your staff will be more likely to make the right choices. The consequence of going through a copyright infringement lawsuit is not worth the stolen image. The integrity you lose with yourself, with your students, with your colleagues and with the community is not worth the lie of a manipulated news photo. It is our job to steer them away from regretful photographic choices. LT THE GENTLE TOUCH The original photo on the left leaves much to be desired. It is dull and lifeless even though compositionally, it is a good photo. However, the color and darkness take away from it. Color balance and a small amount of dodging on the faces in the foreground make the photo pop. Further, it’s what the human eye would have seen. It does not try to deceive the reader. Inspire 15 JEA FALL 07 AD 9/13/07 12:14 PM Page 1 Volumes Premier from Lifetouch You’ve seen the rest, now see the best in online-yearbook creation! Imagine . . . • a revolutionary new website….. easy to use and powerful, with no other software needed • a one of a kind Page Builder featuring drag-and-drop template placement, drag-and-drop image placement Imagine . . . • the ability to add backgrounds, borders and frames in a click • the ability to create a multi-page index effortlessly • an Adviser Task Area to assign tasks to students and a comprehensive Resource Room with training Video Clips • FAQ’s on every page no matter where you are on the site • direct contact with Creative Services and Customer Care through the website and an 800 number for Customer Care questions Imagine . . . • easily adding a CD to your book, with photos directly from the website, or videos and sound clips. With Lifetouch Interactive Memories you can create an exciting supplement to your printed book that will preserve memories for a lifetime. To learn more about Volumes Premier, contact 1.800.736.4704 for a Lifetouch yearbook representative in your area. Imagine creating your yearbook, your way with Volumes Premier from Lifetouch!