Beginning to write with word processing: Integrating writing process

advertisement

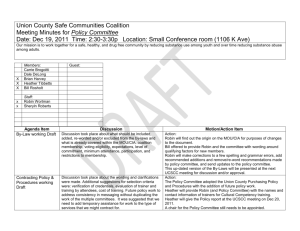

CHARLENE A. VAN LEEUWEN MARTHA A. GABRIEL Beginning to write with word processing: Integrating writing process and technology in a primary classroom fStechnology becomes ubiquitous, teachers can support students' writing development in new ways. n a state of organized chaos, students return from their outdoor recess, grab their snacks, and retrieve their notebooks and pencils for writing workshop. One student approaches the teacher asking, "Whose turn is it to use the computers?" Although Sarah (all names are pseudonyms) is disappointed that it is not her turn today, she quickly finds Alex, one of the students chosen to work with the word processor, and shares the good news with him. This information galvanizes Alex into action as he packs his remaining snack away and darts over to the computer corner, anxious to begin his new piece of writing. This scene might occur in many elementary schools throughout North America today. As federal, state, and provincial governments provide substantial monies for placement of computer technologies in schools, the question remains how best to use this resource in the context of 21 st-century classrooms. The purpose of this article is to explore one focused use of these computer technologies and, in particular, to describe the writing behaviors demonstrated by a group of grade 1 students who used word processors to support their writing. What does the literature say? Educators have responded to new conceptions of student learning and the emergence of digital r4 0, technologies with continual searches for effective teaching and learning strategies to meet the needs of 21 st-century learners (Leu, 2001; McKenzie, 2000; Turbill, 2002). The integration of the new literacies of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the curriculum has become a goal for literacy educators (International Reading Association, 2001; International Reading Association & National Council of Teachers of English, 1996; International Society for Technology in Education, 1998; Kinzer, 2003). The integration of ICTs at the classroom level includes the use of word processors as tools supporting the writing process, the focus of this study. Sociocultural theories of literacy recognize and acknowledge the importance of the social context along with the background experience and skills of students (Bruner, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978). Much of the research on writing, computers, and young children is grounded in the work of these social and cultural theories of language and classroom interaction (Bigge & Shermis, 1999; Cochran-Smith, 1991; Daiute, 1988). Research has demonstrated that communication patterns among students in classrooms change when word processors are introduced as writing tools (Dickinson, 1986; Fisher, 1994; Kumpulainen, 1994; Shilling, 1997). Leu (2002) has pointed out that literacy learning has become increasingly social as technologies and classrooms are integrated. Using a word processor may facilitate meaning making as students and teachers interact within the context of a process writing approach. Student talk and reflection can facilitate sharing and construction of knowledge in a social setting such as a primary classroom. 2007 International Reading Associa tion (pp. 420-429) doi:10.1598/RT.60,5.2 There are effects on educators as well. Teachers' philosophy, pedagogy, and instructional practices with regard to ICT use directly influence outcomes (Russell, Bebell, Cowan, & Corbelli, 2002). If there is a shift to a more collaborative approach in the environment of a classroom, then the role of the teacher supporting the writing process is also transformed (Cochran-Smith, Paris, & Kahn, 1991; Mercer & Fisher, 1992). The teacher becomes facilitator, guide, and participant in a learning community when engaged in computer-based activities (Labbo, 2004; Snyder, 1993). Even greater transformations of the role of classroom teachers may be emerging. Although Cuban (2001) argued that despite increased access to ICTs, meaningful changes in the instructional practices of teachers have not occurred, Leu, Karchmer, and Leu (1999) proposed that "just as new technologies change literacy, literacy also changes new technologies within a transactional relationship" (p. 638). These researchers suggested that in order to keep pace with the changing role of technologies in literacy classrooms, reflective teachers will increasingly determine and share effective ICT integration in the classroom. Integrating ICTs frequently requires modification of teaching strategies employed by educators. The use of computers not only affects classroom culture and the social interactions of students and teachers, but also it introduces a new technology (Baker, 2000; Sandholtz, Ringstaff, & Dwyer, 2000). The use of a different tool-a computer with wordprocessing software-to complete a task traditionally completed with pencil and paper introduces a new realm of possible differences in attitudes, interactions, instructional strategies, and written products (Wood, 2000). In doing so, use of a new tool raises questions with regard to best practices for students at all levels of writing development. This case study sought to examine the impact that different writing tools had on the writing of beginning writers in the primary grades. The study focused on a class of grade 1 students, including aspects such as the physical environment, classroom culture, instructional goals of the teacher, interactions among students, teacher-student interactions, and the development of student writing while using a word processor. This work is a component of a larger study that included students from three primary classrooms (grades 1-3). Methods This research was conducted in a grade 1 class in a rural school in a province on the east coast of Canada. The purpose of the case study (Stake, 1994) was to develop greater understanding of the multiple factors involved in the use of word processing by beginning writers, as well as the effect of integrating ICTs on the classroom environment and on the teacher. The first author (Van Leeuwen) spent hours observing in the classroom, examining variations in student writing behavior, the classroom culture, and communication about writing projects (Patton, 2002). Six boys and seven girls in grade 1 participated in this study; all of them had previous computerbxperience either at home or through their kindergarten program. Data collection and analysis Information was collected from classroom observations, informal conversations with the teacher during field visits, interviews with students and the teacher, and student writing samples (Marshall & Rossman, 1999). Observation sessions and interviews were audiotaped and transcribed to capture oral-language interactions of students with peers, the teacher, and the researcher. Classroom visits occurred every three weeks throughout the school year for 40 to 90 minutes per visit. Students were observed to see how they used the two writing media, word processing or pencil and paper. During classroom visits, samples of handwritten and word-processed texts produced by the children were collected, and informal conversations were held with the teacher. Short interviews, lasting about 10 minutes, were conducted with four students to further explore their approaches to writing with the two media. These four students were representative of a range of characteristics such as gender, kindergarten attendance, and computer experience. Students were asked how they prepared to write, where they found their ideas for writing, and whom they approached for help. Field notes written after each visit captured as many of the activities and actions of the students in the classroom as possible. The perspective of the classroom teacher was explored through informal conversations during field visits and through a semistructured interview. 0 Beginning to write with word processing 600 Topics discussed in the interview included the following: "•aspects of student behavior, "•qualities of student interactions, "•observations of students during writing sessions, "•professional experiences, and "*the teacher's approaches to writing and technology. Technology and teaching experiences The field notes were annotated to compile information from the notes, audiotapes, and writing samples. Student writing samples were collected and assessed using criteria developed by Alberta Education, Student Evaluation Branch (1997). This information was coded by one coder, using themes identified in the literature such as attitudes toward writing and the teacher's writing instruction (Clements, 1987; Cochran-Smith et al., 1991; Mercer & Fisher, 1992) as well as emerging themes. Emerging themes included interactions with peers, skill transfer, and classroom dynamics. An iterative coding process was used until all annotated notes were reviewed and coded (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The grade 1 class In Robin Neville's grade 1 classroom, students' desks were arranged in small groups in the center. Around the periphery of the room were a music corner with piano, chairs, and couch; the teacher's work area and desk; low shelving filled with children's books, math manipulatives, and other art supplies; and the computer corner. The three computers in the classroom were older Apple machines. In contrast, the school's computer lab contained 18 new computers, with 3 other computers located outside the lab in the nearby resource center. The culture in Robin's classroom reflected a focus on productive and enthusiastic activity. Helping her grade 1 students become readers and writers was a high priority. Children were involved daily in a process writing approach as they worked on prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing the various texts they produced. Expectations were clearly communicated at the oOO SThe Reading Teacher Vol. 60, No. 5 start of writing time and were reviewed at the end. During writing workshop, three students in the class were allowed to work at the computers for the duration of the session. The entire class rotated through these three computers, so that each child wrote using a word processor every one and onehalf weeks. Robin frequently encouraged students who made a discovery on the computer to extend their understanding of that discovery. The following exchange is one example: Robin: I want you to put your name "Nicholas" in between quotes. Nicholas: Quotes? These? Robin: These things...and I want a capital "N." So do that. Nicholas has discovered the shift key and some of the things that it can do. He begins to experiment. Robin notices and encourages him to try a few things. The teacher then asks him to use this newfound option in another sentence. (Observation notes) Students were encouraged to experiment and discover things for themselves in this classroom. They were also asked to apply what they had discovered to other circumstances. Problem solving and responsibility were qualities this teacher sought to develop in students. Teaching experiences play a significant role in what goes on within a classroom, and experiences with technology are no exception. Robin's approach to integrating ICTs and process writing was constantly changing and evolving: This is my fourth year teaching grade 1 and as each year goes by I'm surprised how quickly they catch on to technology...when it comes to writing I think time spent in the lab or developing skills with individuals in the classroom [is time well spent].... Some kids actually write better on a computer or...compose faster using a keyboard than pen and paper.... So my use [of] computers is probably expanding as I go along with grade 1.(Teacher interview) Robin believed that integrating ICTs was important for students and brought old computers in from home to set up in the classroom. These provided the opportunity for grade 1 students to have consis- February 2007 4 tent access to a word processor to support their writing. Findings Student attitudes toward writinq and computers For the most part, students' attitudes toward the writing they did in their classroom were positive. When engaged in writing tasks students were generally focused. They were enthusiastic writers both on and off the computer. Students were often observed counting the number of sentences they had written. Their body language demonstrated excitement with their progress. Students' enthusiasm to share their finished work (both handwritten and computer generated) was equally intense. Robin placed a high value on writing and found that students in the class were very motivated when involved in writing. She described how students spoke about writing: Are we having writing time today? When is our writing time? Can we go into the computer lab, to finish up a story? Can I share it with the class? Using the computers was something the students enjoyed. Robin said that "even with the ancient technology in my room, there's still.. .novelty in.. .using the computer to write" (Teacher interview). Of the four students interviewed about their writing tool preference for composing the first draft of a story, three indicated their preference was for a word processor, and one student preferred to use paper and pencil. Students expressed their concern with the mechanics of writing and the efforts involved with letter formation, spelling words, typing on the computer, and creating pictures to illustrate their story. This is expressed in the following conversation: Researcher: Why do you like the computer more? Because, like, we don't have to draw the Nicholas: shapes, all you have to do isjust press the buttons. Researcher: Now, when you say "draw the shapes," do you mean making the shape of the letter? Nicholas: Yeah. (Observation notes) The effort involved in writing with paper and pencil was a major challenge; students spoke of their hands tiring when they wrote that way. In contrast, students enjoyed hunting for letters on the keyboard. Classroom observations confirmed students' stated preferences related to different writing tools-pencil and paper or keyboard-when composing a story. Teacher instruction Robin indicated that developing keyboarding skills and some familiarity with basic wordprocessing functions were among the primary goals for word-processor use in this classroom. To accomplish this, a variety of instructional strategies were used, such as *encouraging students to continue their efforts, "*helping students focus on the important details, and "*supporting students as they developed problem-solving strategies. Most writing skill instruction was a mixture of large-group teaching, followed by individual student-teacher conferences focused on a piece of the student's writing. In contrast, instruction in word-processing skills was approached differently. Large-group lessons were not often used. Wordprocessing instruction was frequently embedded in lessons designed to teach both writing and wordprocessing skills, followed by an opportunity for practice. The following is from a lesson on capital letters and punctuation, and it provides a sense of how this was accomplished: Robin has students sit on the floor near a monitor so that they all can see what is happening. Agroup lesson on capital letters and punctuation is the focus. A file with the "daily message" is called up. Students are instructed to read the message and then correct the missing capital letters and punctuation. Robin demonstrates several ways to make capital letters. Two students are asked to help demonstrate the tasks, and they come over to the keyboard to do this. (Observation notes) Often word-processing instruction took the form of short minilessons slipped into the middle of a writing session. Minilessons were not often planned in advance of the session. They were a response to student questions or emerging student needs, or they were presented when 0 Beginning to write with word processing @00 Robin wished to share strategies helpful for the entire class. While circulating to observe students' writing, Robin provided advice or guidance on writing skills or conventions to individual students. This one-to-one coaching was extended to include word-processing functions when students wrote with word processors. Another aspect of instruction was the writing conference. While Robin conducted writing conferences with individual students in the classroom, this was not the situation in the computer lab. In the computer lab, students requiring help with wordprocessing functions or hardware problems were competing with students who needed guidance about their writing. Conferences in the lab generally took place at the computer, were of shorter duration, and were focused on smaller segments of text. Interactions Interactions between teacher and students, and among students themselves, occurred frequently in the writing process classroom, as well as in the computer lab. The audiotapes from many of the observation sessions revealed the constant hum from conversation when students were writing. There were differences observed in the amount of talk among students depending on where they were writing; the amount of talk in the computer lab was consistently higher than in the classroom, Students were blatant eavesdroppers. Many times they would enter into an interaction by volunteering information or assistance: Kayla looks at me and asks, "How do you spell once?" I ask her how it would start and she says "0-U-C." Maria, sitting at the next computer listening to our conversation says, "Iknow how to spell it." She points to her screen. Kayla scoots around the computer table to see how to spell once. She returns then to her computer and resumes typing. (Observation notes) These interactions may also have begun with students narrating their own actions as they were faced with a task on the computer. Something that frequently emerged from these exchanges between students was the discovery of another word-processor function. In this way, students became peer coaches. It did not matter who taught the students a skillteacher or peer. If the children wanted to know how C424 The Reading Teacher Vol. 60, No. 5 to do soi nething, they were satisfied as long as their question was answered. Rob in constantly interacted with students conceming their writing in the classroom and in the comput -r lab. Aside from regular editing conferences, stte helped students with a variety of revisions to their vvork. The focus tended to be on writing conventions and skills taught to the class. Robin also pointed out differences in student-teacher interactions in the computer lab; students did not need as much atitention and developed skills in working independe ntly. Robin speculated that these observed differen ces might be the result of students' high level of con centration on typing words. The last form of interaction occurred with the revision of computer-based writing, when students read the text displayed on a classmate's monitor. Students sometimes offered comments on writing they hacIjust read. Students were never observed doing th is with a classmate's handwritten work. Writing behaviors Stuclents' writing behaviors using paper and pencil or word processing revealed some intriguing differenc-es in the amount of focused writing time, reading and rereading behaviors, and planning of their wr:iting. Students with strong writing skills working in a notebook with a pencil were frequently able to sustain their focus on a writing task longer tihan when they worked on the computer. Almost all students with poorer keyboarding skills seemed to slow down in terms of text production after 10 or 15 minutes, whether students were composing n ew pieces or transcribing i their writing. Reap ding and rereading handwritten work appeared t o be for reflection and for determination of what should come next regarding story development and content. On the computer, reading and rereadin g was for assessment of what students had typed arid of whether the correct keys had been used. Re reading appeared more frequently during word pn ocessing and occurred in short bursts. In contrast, students reviewing handwritten work revealed I onger, more sustained rereading of their piece of writing. This was particularly obvious during com1 osition of a first draft. Whe,n students were asked how they prepared to write, they reported using a variety of strategies. Some st ated that they first prepared their writing February 2007 tools. Others reported that "thinking" was their starting point. Some students read or reread a book they had enjoyed in preparation for writing, and others sat down to consider which of their personal experiences they wanted to write about. All of these strategies were used in the classroom during traditional writing process sessions, but fewer strategies were used when beginning to write with a word processor. Writinq sample analysis The quality of each of the writing samples was assessed on three criteria-ideas and order, words and sentences, and conventions of language. Analysis of the writing samples revealed that word processors did not reduce the quality of writing of these grade 1 students; that is, word-processed and handwritten pieces were of similar quality. However, there was a difference in the length of the texts. Writing samples composed with pencil and paper were generally longer than those composed with a word processor. There was a range from 73 to 305 words and a mean of 163 words for handwritten work, compared with 37 to 116 words and a mean of 71 words for pieces composed with a word processor. Discussion Teacher instruction As the integrated use of computers becomes more commonplace in primary-grade curricula, developing a greater understanding of the computer's impact on instruction is increasingly important. Tailoring writing instruction to the context is an important aspect of effective instruction (CochranSmith et al., 1991; Mercer & Fisher, 1992; Sandholtz et al., 2000; Snyder, 1993). One challenge of group lessons in the computer lab stems from the students' desire to begin to use the computers. They are not easily engaged by a demonstration lesson that is not hands-on for them. Lesson timing may need to be a more important consideration based on the finding that almost all students with poor keyboarding skills started slowing in their production of text after 10 or 15 minutes. If students start to lose focus, teachers need to consider different ways to break up keyboard- ing time so the final portion of the writing period is used effectively. The midpoint of a writing session with word processors may be better timing for a minilesson than at the beginning, when students are eager to use the computers. Classroom Interactions The types of interactions observed, comments by the teacher, and responses drawn from the student interviews reveal the power and frequency of peer interactions. Observations revealed that students relied on one another for help with spelling and word processing functions. This is similar to findings by Labbo (2004); Lomangino, Nicholson, and Sulzby (1999); and Philips (1995). The help that students provide one another redirects some of the demands on the teacher's attention, enabling the teacher to focus on higher-level questions and problems. Such help also enhances students' problem-solving skills. Most help provided by students to their peers was in the form of direction and generally did not incorporate explanation. This confirms the importance of peer interactions while recognizing the limitations of such assistance. Classroom observations revealed that the teacher was more tolerant of student talk in the computer lab setting. Increased talk among peers suggests that teachers need to accept a greater degree of interaction in a computer lab. This increased tolerance of student interactions while using the computer may have encouraged students to help their peers. Some research into collaborative writing has found improvements in the quality of writing when students engage in metacognitive talk about their text (Dickinson, 1986; Jones & Pellegrini, 1996). This suggests the possibility that allowing greater task-related interaction among students when they are writing with word processors may result in improved writing quality. The one-on-one interaction of a writing conference was different when conducted in a computer lab as compared to the classroom. Content was different because various word-processing skills or keyboard issues were frequently addressed. Conferences were shorter in the computer lab because the teacher and student did not work through the entire text in one sitting but addressed one or two issues, and then the student returned to writing. This may be due to challenges in redirecting the 0 S Beginning to write with word processing Oos S student's attention from the computer to the text. This could also be the result of students' demands for speedy assistance with word-processor-related functions in order to continue with their writing task. Writing conferences generally took place at the student's computer workstation where constraints of the physical environment may have played a role. The teacher and student did not move to a separate table or area of the room to signal to others that a writing conference was in progress. This seemed to give other students greater license to interrupt the conference, given the more diverse demands for assistance in the computer lab. The physical effects of standing bent over a computer screen for several minutes to conduct a writing conference may also have an impact. Writing behaviors In this study, observations of students writing with computers reveal that they rarely create a story web or plan. One reason for this may be that making changes with a word processor is easier, and writers count on the revision process to refine their work. Previous research has not determined how reduced planning affects the quality of grade 1 students' stories. There has been speculation that writers compensate for this reduction in planning by reading and rereading their work (Haas, 1989). The current study did find differences in the reading behavior of participants when composing, with short, more frequent reading of word-processed text. This shift in reading patterns was also found in a study of slightly older students in Australia (Sutherland-Smith, 2002). Frustration and reluctance were more frequently observed in students when they were transcribing, a less interesting task compared to composing. This is also a finding in studies with older students (Cochran-Smith et al., 1991; Mumtaz, 2001; Seawel, Smaldino, Steele, & Lewis, 1994). The keyboarding skills of younger students did not appear to interfere with their composing because very beginning writers have a slower composing and inscribing rhythm (Cochran-Smith et al.). Incorrect finger positioning did not seem to impede students' success or enthusiasm in using a keyboard, an observation also noted by Gemmell (2003). Even students who expressed a preference for handwriting (42 The Reading Teacher Vol. 60, No. 5 stories s1till had strong interest in using the computers. qo participant ever said that he or she would rather not use the computer. Writ ing behaviors observed in the computer lab migh t also result from students' differing levels of conce ntration when typing words. Alternative explanati ons for these differences in behavior may be that st udents are more autonomous in this environment, or more motivated to try invented spelling on the ccimputer because editing is easier. Another potential explanation is that they are more absorbed with the technology and, as a result, are less involved wtith the adults around them. Students may have been helping one another more frequently because th ere was a higher tolerance of talk among students in the lab. The combination of influences at work ' vithin the environment and how they shape one anot]her, and the understanding and practices of the teact ler, are likely the source of the observed changes.• This finding is in agreement with Cochran -Smith et al. (1991), Jones and Pellegrini (1996), md Snyder (1994). lerations for classroom Consid pract! ;ee A nu imber of implications for classroom practice emei rged from the findings of this study. When integrati ng word processing and the writing program, teiichers should consider the following: De velop realistic expectations when implementing a word-processing component in the process writing program. When teachers plan to integrate word processing and their writing wo rkshop, a number of questions must be addre ssed. What role will the teacher play? Fac:ilitator, guide, or provider of direct instructioii? When should keyboarding be introduced to children? What word-processing skills shc9uld be introduced to grade 1 students? • Pla n to adjust current instructional strategies. Te•ichers need to develop and adjust instructioinal strategies in order to assist students in carTying out all aspects of the writing prc cess, from prewriting to final revisions. Wcrking with the technology brings a new set of decisions that must be made: Who will wr ite with the word processor today? How February 2007 much work will students do in pairs? Individually? How much peer mentoring will be allowed? Will students be encouraged to assist their peers? " Schedule feedback times for students. Writing conferences play a critical role in the writers' workshop. Teachers must consider how to ensure that appropriate feedback is given to students when they write with a word processor. Will writing conferences happen at computer terminals? At a table away from the bank of computers? Will teacher and student be able to sit down together? Should the student print the piece of writing to be discussed? "*Be prepared for students to focus on the computers, not on a lesson, in the computer lab. In-class preparations before going to the computer lab may need to take on a new focus to address the students' impatience to begin using computers as soon as they arrive. Teachers could give students minimal instruction before leaving the classroom and let them begin working on the computers immediately. A lesson could then be timed to provide a break for students from keyboarding when those with weaker skills begin to lose their focus, probably at the 10- to 15-minute mark. - Teach students skills in working collaboratively. Peer teaching can be a powerful tool; however, students need instruction in how to work effectively with one another. What roles will students assume? Which team member should find the next letter? Who could work on checking the spelling? Would peer help be more effective if the peer teacher dictated the next letter or word? Summary This study affords an exploration of how beginning writers learn to write using different instruments, and it also provides further information about the relationships among students, teachers, the writing process, and the use of word processors as tools. The dynamic interplay of influences on classroom culture and on the interactions among individuals within a grade 1 classroom is described. From the observations in this study, it is clear that no one composing tool is able to serve all the needs of beginning writers. Word processors are tools that can complement the range and type of writing activities in elementary school classrooms. The leadership role played by the classroom teacher in implementing word processing in the writing curriculum is a critical component in determining the felicitous use of this tool. Van Leeuwen teaches at the University of Prince Edward Island in Canada. Gabriel teaches at the same university.She may be contacted there (550 University Avenue, Charlottetown,Prince Edward Island, CIA 4P3, Canada).E-mail mqabriel®upeI.ca. References Alberta Education, Student Evaluation Branch. (1997). Classroomassessment materialsproject (CAMP) grades 1&2. Edmonton, AB: Education Advantage. Baker, E.A. (2000). Instructional approaches used to integrate literacy and technology. Reading Online. Retrieved August 15, 2006, from http://www.readingonline.orgl articles/art-index.asp?HREF=baker Bigge, M.L., &Shermis, S.S. (1999). Learning theories for teachers (6th ed.). New York: Longman. Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Clements, D.H. (1987). Computers and young children: A re- view of research. Young Children, 43(1), 34-44. Cochran-Smith, M.(1991). Word processing and writing in elementary classrooms: A critical review of related lit- erature. Review of EducationalResearch, 61(1), 107-155. Cochran-Smith, M., Paris, C.L., &Kahn, J.L. (1991). Learning to write differently: Beginning writers and word processing. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Cuban, L. (2001). Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Daiute, C. (1988). The early development of writing abilities: Two theoretical perspectives. In J.L. Hoot &S.B. Silvern (Eds.), Writing with computers in the early grades (pp. 10-22). New York: Teachers College Press. Dickinson, D.K. (1986). Cooperation, collaboration, and a computer: Integrating a computer into a first-second grade writing program. Research in the Teaching of English, 20, 357-378. Fisher, E. (1994). Joint composition at the computer: Learning to talk about writing. Computers and Composition, 11,251-262. Gemmell, S.(2003). A study of keyboarding instructionand the acquisitionof word processingskills. (ERIC Document Beginning to write with word processing 4 go0 0 Reproduction Service No. ED477756). Unpublished master's thesis, Chestnut Hill College, Philadelphia, PA. Haas, C. (1989). How the writing medium shapes the writing process: Effects of word processing on planning. Research in the Teaching of English, 23,181-207. International Reading Association. (2001). Integratingliteracy and technology in the curriculum (Position statement). Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved September 15, 2006, from http://www.readinq.org/downloads/positions/ps1048. technology.pdf International Reading Association & National Council of Teachers of English. (1996). Standardsfor the English language arts. Newark, DE; Urbana, IL: Authors. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www. ncte.org/print.asp?id=110846&node=204 International Society for Technology in Education. (1998). National educationaltechnology standards for students. Eugene, OR: Author. Retrieved September 15, 2006, from http://cnets.iste.orq/students/s stands.html Jones, I., & Pellegrini, A.D. (1996). The effects of social relationships, writing media, and microgenetic development on first-grade students' written narratives. American EducationalResearch Journal,33(3), 691-718. Kinzer, C.K. (2003). The importance of recognizing the expanding boundaries of literacy. Reading Online. Retrieved September 11, 2006, from http://www.reading online.org/electronic/elec_index.asp?HREF=kinzer Kumpulainen, K. (1994). Collaborative writing with computers and children's talk: A cross-cultural study. Computers and Composition, 11,263-273. Labbo, L.D. (2004). Author's computer chair. The Reading Teacher, 57, 688-691. Leu, D.J., Jr. (2001). Internet project: Preparing students for new literacies in a global village. The Reading Teacher, 54, 568-572. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.readingonline.org/electronic/elec-ndex.as, ?HREF=rt/3-01 column/index.html Leu, D.J., Jr. (2002). Internet workshop: Making time for literacy. The Reading Teacher, 55, 466-472. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.readinqonline.orq/ electronic/elec-index.asp?HREF=/electronic/RT/ 2-02-Column/index.html Leu, D.J., Jr., Karchmer, R.A., & Leu, D.D. (1999). The Miss Rumphius effect: Envisionments for literacy and learning that transform the Internet. The Reading Teacher, 52, 636-642. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.readingonline.org/electronic/elec-index.asp ?HREF=rt/rumphius.html Lomangino, A.G., Nicholson, J., &Sulzby, E. (1999). The nature of children'sinteractionswhile composing together on computers (CIERA Report #2-005). Ann Arbor, Mh: Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED447477) Marshall, C., & Rossman, G.B. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. . • (. The Reading Teacher Vol. 60, No. 5 McKenzie, J. (2000). Beyond technology: Questioning,research, and the information literate school. Bellingham, WA: FNO. Mercer, N., & Fisher, E. (1992). How do teachers help children to learn? An analysis of teachers' interventions in computer-based activities. Learning and Instruction, 2, 339-355. Miles, M.B., & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative dataanalysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Mumtaz, S. (2001). Children's enjoyment and perception of computer use in the home and the school. Computers & Education, 36, 347-362. Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Philips, D.(1995). Evaluationof exploratorystudies in educationalcomputing. Study 6: Using the word processor to develop skills of written expression. Final report. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED387820) Russell, M., Bebell, D., Cowan, J., & Corbelli, M. (2002). An AlphaSmart for each student: Does teaching and learning change with full access to word processors? Paper presented at the 23rd National Educational Computing Conference, San Antonio, Texas. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED475950) Sandholtz, J.H., Ringstaff, C., & Dwyer, D.C. (2000). The evolution of instruction in technology-rich classrooms. In R. Pea (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass reader on technology and learning(pp. 255-276). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Seawel, L., Smaldino, S.E., Steele, J.L., & Lewis, J.Y. (1994). A descriptive study comparing computer-based word processing and handwriting on attitudes and performance of third and fourth grade students involved in a program based on a process approach to writing. Journal of Computing in Childhood Education,5(1), 43-59. Shilling, W.A. (1997). Young children using computers to make discoveries about written language. Early Childhood Education Journal,24, 253-259. Snyder, I. (1993). The impact of computers on students' writing: A comparative study of the effects of pens and word processors on writing context, process and product. Australian Journalof Education,37(1), 5-25. Snyder, I. (1994). Writing with word processors: The computer's influence on the classroom context. Journalof Curriculum Studies, 26,143-162. Stake, R.E. (1994). Case studies. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 236-247). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sutherland-Smith, W. (2002). Weaving the literacy web: Changes in reading from page to screen. The Reading Teacher,55, 662-669. Turbill, J. (2002). The four ages of reading philosophy and pedagogy: A framework for examining theory and practice. Reading Online. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.readingonline.orgrJnteernational]interindex.asp?H REF=turbill4/index.html February 2007 Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higherpsychological processes (M.Cole, V.John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds. &Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1934) Wood, J.M. (2000). A marriage waiting to happen: Computers and process writing. Boston: Education Development Center. Retrieved September 6, 2006, from http://www.edtechleaders.org/Resources/Readings/ UpperElemLiteracy/Wood ComputersWriting.htm Bring engaging literacy instruction into your classroom with ReadWriteThink.org! Discover ReadWriteThink's rich collection of materials for teaching reading and language arts ingrades K-12, including research-based lesson plans, interactive online activities for students, and a calendar of significant literary events-all available online for free. I Less I Standards I - eRsur7e I Student Materials I ;9 - Newark, DE 19714-8139 - 800-336-323 - 302-731-1600 - www.readinq.orq Beginning to write with word processing 0 29• COPYRIGHT INFORMATION TITLE: Beginning to write with word processing: Integrating writing process an SOURCE: The Reading Teacher 60 no5 F 2007 PAGE(S): 420-9 The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher: http://www.reading.org/