A contribution to discussion on a national languages policy

advertisement

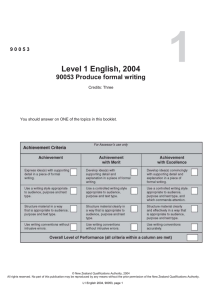

NEW ZEALAND ASSOCIATION OF LANGUAGE TEACHERS P O Box 132 260, Sylvia Park, Auckland 1644 Patron His Excellency Lieutenant General The Right Honourable Sir Jerry Mateparae, GNZM, QSO, Governor-General of New Zealand A contribution to discussion on a national languages policy for Aotearoa/New Zealand Key issues: The New Zealand Association of Language Teachers (NZALT) represents the interests of over 600 teachers of languages (other than English or Māori as first languages) from the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. We believe that a coherent national languages policy for New Zealand must include clear and transparent discussion of the so-called ‘international languages’, just as Waite (1992) had done. We contend that for a national languages policy to be truly inclusive in New Zealand it must, as Waite himself acknowledged, take account of the importance of international languages. The dilemma and challenge for us as a professional association is that, in the twenty years since Waite and surrounding political messages about the importance of international language and cultural skills, we have witnessed effectively zero growth in the numbers of students in schools opting to take international languages to any degree of meaningful proficiency (i.e., above the most basic or ‘beginner’ levels) Fundamentally, a national languages policy can help by raising the profile of all languages for New Zealanders in much the same way as Waite (1992). If it fails to do so, it cannot be said to be promoting ‘a fair go for all’. The reality is that, twenty years on from Waite, the acquisition of international language skills among young New Zealanders is in many cases mediocre, to say the least. A national languages policy that recognises this is sorely needed. The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology In the broader context of recognising the importance of English and Māori as first languages in New Zealand, the New Zealand Association of Language Teachers (NZALT) is the professional organisation that represents the interests of over 600 teachers of languages (other than English or Māori as first languages) from the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. Our particular interest as a professional association is in those languages that were termed ‘international’ in the original discussion document that represented the first attempt to introduce a coherent national languages policy for New Zealand - Aoteareo: Speaking for ourselves (Waite, 1992). Our specific focus is on the five common international languages currently taught as additional languages (i.e., languages other than students’ first language) in New Zealand’s schools (Chinese, French, German, Japanese and Spanish). Also, more broadly, we have an interest in all those international languages (such as Indonesian, Italian, Korean and Russian) that have been taught, at one time or another, in New Zealand’s schools, and that continue to be taught in New Zealand’s tertiary sector. We also support the teaching and learning of any additional language in schools (including te reo Māori, Pasifika and community languages, and classical languages). We are mindful of the call from the Royal Society of New Zealand for views from a range of interested parties on the current provision of language support in New Zealand society as the Royal Society works on preparing a paper to document what is known about the efficacy of languages policies. We are also mindful that, in its call for submissions, the Royal Society (2012) notes both that “this year marks the twentieth anniversary of [Waite, 1992] and provides a timely opportunity to revisit the national discussion about languages and their place in New Zealand” (¶ 2), and that the call for submissions “aims to offer a fresh starting point for further discussion of cross-sector approaches to language provision and policy in New Zealand” (¶ 3). As a contribution to this ‘fresh starting point for further discussion’, this submission documents the reasons why we believe that a coherent national languages policy for New Zealand must include clear and transparent discussion of the so-called ‘international languages’, just as Waite (1992) had done. That is, mindful to take on board the distinctive factors that made up New Zealand’s linguistic landscape, Waite (1992) classified languages into several groups (Figure 1). These groupings offer a starting point for a discrete focus on the international languages: Notes 1 LOTEMs – Languages other than English and Māori. 2 NZSL – New Zealand Sign Language Figure 1: Languages for New Zealand (Waite, 1992) The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology We are mindful that in many debates surrounding language policy and planning in New Zealand it can often appear that Māori, Pasifika and community issues are dominant. For example, the programme for the 2012 New Zealand Diversity Forum, in the context of which the Royal Society held an open consultation on its languages policy initiative, suggests that presentations focused predominantly on issues such as human rights in local communities, or for migrant workers, or for Pacific peoples. These were presented in the context of the overarching theme of ‘Aotearoa, a fair go for all.’ NZALT as an organisation fully supports issues of human rights for local communities, migrants, and Māori and Pasifika peoples, and we acknowledge that the extent to which the Diversity Forum can act as a catalyst for genuine and positive change is the extent to which it is valuable and worthwhile. We also recognise that recent decades have witnessed a shift in national languages policies in various Western societies towards taking greater account of minority (indigenous and migrant) languages (Norrby & Hajek, 2011). We contend, however, that for a national languages policy to be truly inclusive in New Zealand it must, as Waite himself acknowledged, also take account of the importance of international languages. Waite’s discussion of international languages had drawn a specific link between language learning and the potential for improved national economic performance. For example, Waite quotes the National Government’s Education Minister at the time, Alexander Lockwood Smith: Our economic growth is linked directly to our ability to succeed in an increasingly competitive international economy and an increasingly high-tech environment. In response to this … while maintaining our traditional links with English-speaking countries, we must become more familiar with the languages and cultures of the dynamic countries of East Asia and the European Community. (Waite, 1992, p. 4, our emphasis) The argument that New Zealand is essentially a trading nation, to a very large extent dependent on establishing and maintaining effective relationships with trading partners all over the world (and, by implication requiring significant proficiency in international languages and their cultures), was underscored in several other publications of the early 1990s (e.g., Callister, 1991; Crocombe, Enright, & Porter, 1991). Indeed, in tandem with the publication of Waite in 1992, the public political message was that “we really must learn to speak other languages.” This was Don McKinnon’s (1992, p. 1) argument, in his capacity as the National Party’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, in a speech entitled ‘English is not enough’. McKinnon went on to argue: The curricula in New Zealand schools and courses available in universities must equip young people with language and cultural skills. … New Zealand’s ability to earn a living – our very future in fact – depends on young New Zealanders acquiring international language skills. (p. 1, our emphasis) The linking of international languages to economic advantage for New Zealand, although paramount in the dialogue in the early 1990s, represents but one of many reasons why we believe access to an international language is important for New Zealand’s young people. Indeed, Gallagher-Brett’s (2004) publication documents 700 reasons for studying an additional language, grouped around 70 themes, including promoting academic skills, autonomy, citizenship, critical thinking, democracy, diversity, equal opportunities, identity, intercultural competence, and personal and social development. The economic advantage for New Zealand provides one lens of several lenses through which to view the vital importance of acquiring skills in international languages. The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology The dilemma and challenge for us as a professional association is that, in the twenty years since Waite and the surrounding political messages about the importance of international language and cultural skills, we have witnessed effectively zero growth in the numbers of students in schools opting to take international languages to any degree of meaningful proficiency (i.e., above the most basic or ‘beginner’ levels), thereby ensuring levels of proficiency that might give students ‘international language skills’ that will help New Zealand to ‘earn a living.’ That is, we applaud the positive move, in New Zealand’s revised school curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) that has created a new learning area dedicated to the learning of additional languages, Learning Languages, and the entitlement to learning a new language that is now in place for students in school years 7 to 10. We also applaud the initiatives that have been put in place to strengthen provision for international languages, particularly in the intermediate school sector, through dedicated professional development and targeted resources. These have led to growth in the intermediate school sector. However, several fundamental problems for the teaching and learning of international languages remain which, in the absence of a national languages policy, may not be addressed adequately in the foreseeable future. That is, the fact that the learning of an additional language is now an entitlement for all students in Years 7 to 10 sounds good in theory, but effectively leads to several problems: 1. Learning an additional language is not compulsory at any stage of schooling 2. This means that, although schools are required to offer some kind of programme in additional languages to students in Years 7 to 10, students are not required to take up the offer 3. The entitlement is only to be applied to Years 7 to 10. There is no entitlement prior to Year 7 or in the senior secondary Years 11 to 13 (although, having said that, we know that many schools have offered successful programmes in additional languages to students in Years 11 to 13 for many years, and there is, at present, no reason to think that this might change) 4. The entitlement has not led to significant gains in enrolments into languages courses in the senior secondary years (indeed, evidence from subject enrolment statistics suggests negligible growth at the secondary school level from 1992 to date) 5. The entitlement embraces the whole range of additional languages for New Zealand (see Figure 1 above), including English, Māori and Pasifika languages alongside the international and classical languages. Seen from the perspective of equity and access, this is a good thing (or, put another way, a ‘fair go for all’). In practice, this leads to a situation in which: a. students may be offered a whole collection of languages, often delivered as short-term ‘tasters’, which have neither breadth nor depth; b. conversely, schools may often time-table different languages at the same time, thereby providing limited choice to students, and narrow (or no) opportunity to study more than one language; c. all languages are treated as equal in terms of what this means for learning. That is, the differential demands of different languages (for example, the additional demands, for English as first language speakers, of learning an Asian language in comparison with a considerably more cognate, and Roman-alphabet dependent, European language, and the time implications of this) are not taken into account; d. students may in fact not be offered any opportunity to learn an international language. 6. The entitlement itself is something that schools and Boards of Trustees are required to be “working towards” (Ministry of Education, 2007) (p. 44) rather than mandating. Even the entitlement is not really an entitlement. The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology The above factors have significant implications for the numbers of students who may move on to study a language at tertiary level, and for the levels of proficiency that students can reach, at both secondary and tertiary level, in a given international language. It would seem that, despite a revised curriculum, very little has been done to promote the interests of international language teaching and learning in ways that have boosted numbers, interest and proficiency significantly. Additionally, treating all languages as ‘equal’ in terms of learning means that those students who do choose to study a language at the post-school level may often struggle because they do not have sufficient competence to cope with the demands of tertiary level language study (this problem is particularly acute for the Asian languages). Ultimately, a high proficiency level (or lack thereof) has implications for future graduates, several of whom may wish to enter the teaching profession as teachers of international languages. The ‘cycle of lack’ may therefore be perpetuated. Hu (2005) argues: Policy decisions on the starting age for foreign language education need to take into account a large number of contextual and resource factors. Early instruction itself is not a sufficient condition for effective learning to occur; there are other conditions that are required, for example, the availability of teachers with a high level of proficiency in the target language and professional training, rich opportunities for authentic communication in the language, ample instructional time, teaching methodology geared to the learning needs of young children, as well as consistent and well-designed follow-up instruction in the higher grades. (p. 18). We contend that, if the teaching and learning of international languages (or, for that matter, any additional language) is to have any opportunity for real and lasting success in New Zealand, with learners of international languages being able to reach the highest levels of proficiency, Hu’s (2005) principles must be taken into account. In turn, we would argue that a national languages policy for New Zealand must include, just as the Waite report did, a discussion of the fundamental importance of international languages for New Zealand alongside recommendations to strengthen international language provision in schools and universities. Indeed, we recognise that crucial in the decision to introduce the new learning area Learning Languages were two international critiques (Australian Council for Educational Research, 2002; National Foundation for Educational Research, 2002), both of which noted the low priority given to learning languages other than the language of instruction in the original curriculum framework document (Ministry of Education, 1993). We contend that failure to deal with the low take-up of study in international languages via support from a national languages policy will open us up to further international critique. How can a national languages policy help in securing more meaningful and substantial gains in international language proficiency? In the interests of promoting ‘a fair go for all’, this submission has isolated international languages as a discrete component of the linguistic landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our focus is not intended to be exclusive. Rather, we have wished to throw the spotlight on international languages as a particular dimension of language use in Aotearoa New Zealand at this time, so that ultimately the arguments around international languages can be laid alongside those around indigenous, heritage and community languages, and a genuine fair go for all can be achieved. Fundamentally, then, a national languages policy can help by raising the profile of all languages for New Zealanders in much the same way as Waite (1992). That is, on the one hand, a national The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology languages policy must address key problems for New Zealand around the maintenance and enhancement of Māori, Pasifika and community languages. As an organisation, we fully support this, and applaud the efforts being made to promote a fair go for these languages and their peoples. On the other hand, a national languages policy must address parallel key problems for New Zealand around the maintenance and enhancement of international languages. If it fails to do so, it cannot be said to be promoting ‘a fair go for all’. We contend that part of addressing key problems for international language learning in New Zealand must be to challenge the Government to look carefully at its provision for language learning (whatever the language), particularly in schools. This careful look needs to include: 1. considering some level of compulsion to study an additional language at some stage of schooling, thereby ensuring that there is at least some access to additional language learning for all (current experience shows that where there is wiggle room (“working towards …”) schools and learners opt out); 2. considering encouraging opportunities for students to study both Māori (and/or a Pasifika/community language) and an international language at some stage of schooling, thereby broadening students’ choices and experiences; 3. investing in high quality tertiary and teacher education programmes that can focus on providing not only graduates (for society) but also teachers (for schools) “with a high level of proficiency in the target language and professional training” (Hu, 2005, p. 18, our emphasis). In turn this will facilitate high quality learning experiences for students, especially at the higher levels. We recognise that the priorities of Government in 2012 may be very different to priorities in 1992. Nevertheless, the political messages for New Zealanders in the early 1990s, and reinforced through the Waite report, arguably have on-going significance: “We really must learn to speak other languages” because our future “depends on young New Zealanders acquiring international language skills” (McKinnon, 1992, p. 1). “Our economic growth is linked directly to our ability to succeed in an increasingly competitive international economy … we must become more familiar with the languages and cultures of the dynamic countries of East Asia and the European Community” (Smith, quoted in Waite, 1992, p. 4) Our education system “must adapt … we need a work-force which … has an international and multicultural perspective” (Ministry of Education, 1993, p. 1). These ‘internationally-focused’ political aspirations of twenty years ago are framed as imperatives … things that must occur. The reality is that, twenty years on, the acquisition of international language skills among young New Zealanders is in many cases mediocre, to say the least, and arguably insufficient to contribute substantially to these priorities. A national languages policy that recognises this, alongside the promotion of ‘a fair go for all’, is sorely needed. David Hall President, NZALT Martin East Junior Vice-President, NZALT It should be noted that the views expressed in this submission, whilst made by the President and Junior Vice President of the New Zealand Association of Language Teachers on behalf of the Executive of NZALT, do not necessary reflect the views of all members of the Association The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology References Australian Council for Educational Research. (2002). Report on the New Zealand national curriculum. Melbourne, Australia: ACER. Callister, P. (1991). Expanding our horizons: New Zealand in the global economy. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Planning Council. Crocombe, G. T., Enright, M. J., & Porter, M. E. (1991). Upgrading New Zealand's competitive advantage. Auckland, NZ: Oxford University Press. Gallagher-Brett, A. (2004). Seven hundred reasons for studying languages. Southampton, UK: University of Southampton Subject Centre for Languages, Linguistics and Area Studies. Hu, G. (2005). English language education in China: Policies, progress, and problems. Language Policy, 4, 5-24. McKinnon, D. (1992). Minister of Education and Trade. Speech presented to the Asia 2000 ‘Realising the Opportunities’ Seminar, May 1992. Press release from the office of the Minister of External Relations and Trade. Ministry of Education. (1993). The New Zealand Curriculum Framework. Wellington, NZ: Learning Media, Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, NZ: Learning Media. st National Foundation for Educational Research. (2002). New Zealand stocktake: An international critique. Retrieved 1 March, 2004, from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/index.cfm?layout=document&documentid=7258&indexid=1004&indexparentid=10 72. Norrby, C., & Hajek, J. (Eds.). (2011). Uniformity and diversity in language policy: Global perspectives. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. Royal Society of New Zealand. (2012). Consultation on languages in Aotearoa. Alert Newsletter 726. Retrieved 25th August, 2012, from http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/2012/07/19/alert-newsletter-726/. Waite, J. (1992). Aoteareo: Speaking for ourselves. Part A: The overview; Part B: The issues. Wellington, NZ: Ministry of Education. The Defining Commitments of NZALT Advocacy / Collaboration / Communication / Consultation / Educational Excellence / Efficiency & Continuous Improvement / Expertise / Innovation / Networks / Service Focus / Technology