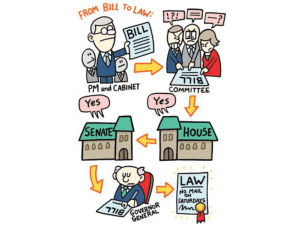

Guide to Making Legislation

advertisement