The PLO Observer Mission Dispute

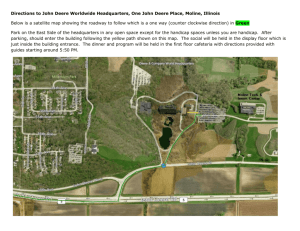

advertisement