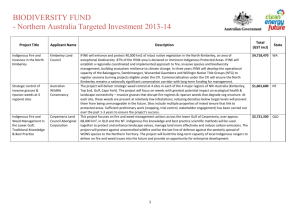

Fire Management in the Kimberley and Other Rangeland Regions of

advertisement