GOOD SOCIETY / GREEN SOCIETY? THE RED–GREEN DEBATE

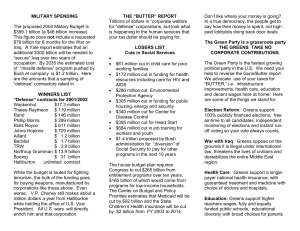

advertisement