International Journal of Music Business Research

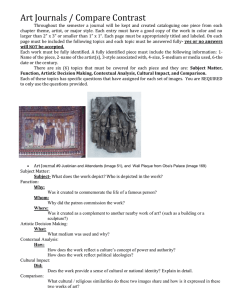

advertisement