Memory expansions for the Commodore 128 - KT

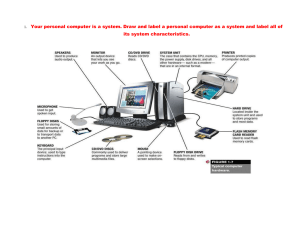

advertisement