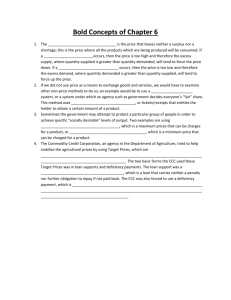

"Pennies on the Dollar": Reallocating Risk and Deficiency Judgment

advertisement