Preparing to Teach in Higher Education

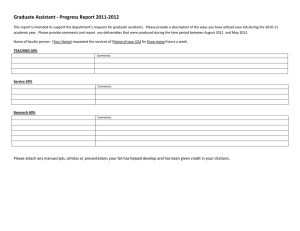

advertisement