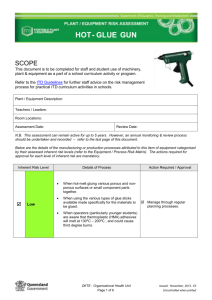

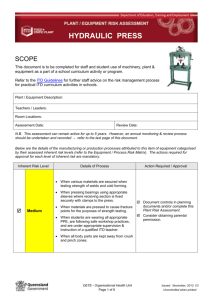

ITD Safety Guideline: Practical Handbook for Schools

advertisement