Summer 2015 - American Academy of Arts and Sciences

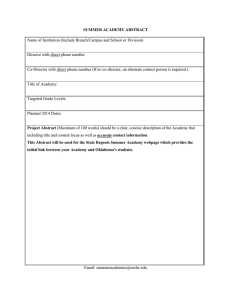

advertisement