Effective Interventions for Ninth Grade Students

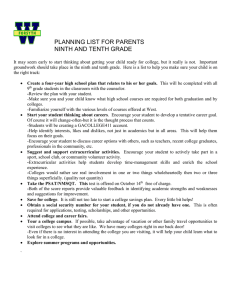

advertisement