Read the full text of Securing the Right to a Safe and Healthy

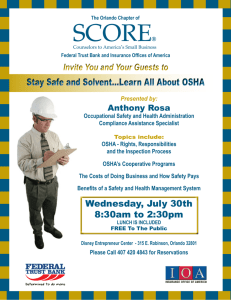

advertisement