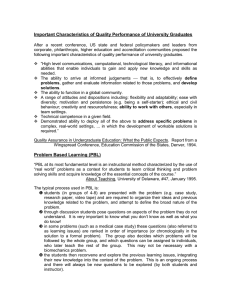

Factors That Influence Performance in a Problem

advertisement