New Developments in European Medical Device Law

advertisement

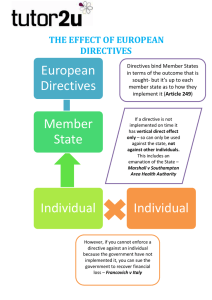

IT’S THE LAW New Developments in European Medical Device Law By Philipp Reusch European medical device law is uniformly harmonized across the individual Member States of the EU, although it is continually subject to amendments, which are significant in practical terms, and there are national variants. This article introduces applicable regulations, illustrates the main reforms brought about by the directive amendment and discusses liability law relating to the importation of goods into the EU. • Council Directive 90/385/EEC of 20 June 1990 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices • European Parliament and Council Directive 98/79/EC of 27 October 1998 relating to in vitro diagnostic devices In accordance with the concept of the New Approach, these directives are currently augmented1 by 308 standards. Overview of Applicable Law Changes in the New Approach—the New Legislative Framework European regulations on medical devices are contained in several directives and ordinances. These include: • European Parliament and Council Directive 2007/47/EC of 5 September 2007 on the amendment of Council Directives 90/385/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices and 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices • Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14 June 1993 concerning medical devices • European Parliament and Council Directive 2000/70/EC of 16 November 2000 on the amendment of Council Directive 93/42/EEC with regard to medical devices containing stable derivates of human blood or human plasma • European Parliament and Council Directive 2001/104/EC of 7 December 2001 on the amendment of Council Directive 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices • Commission Directive 2003/32/EC of 23 April 2003 with precise specifications relating to the requirements laid down in Council Directive 93/42/EEC regarding medical devices manufactured using tissue of animal origin At present, many of the provisions of these directives are undergoing changes, including the New Approach concept itself. The aim of the concept,2 introduced in 1985, was the technical harmonization of certain products and thus the promotion of trade within the EU. The objective was to allow manufacturers as much autonomy as possible in the manufacture of their products. Government control was to apply mainly to monitoring products already on the market. Apart from that, government oversight was only considered in the case of products with a particularly high risk potential. At the same time, the objectives of guaranteeing citizens’ safety and health and protecting the consumer were pursued. The New Approach has been revised by the decision of the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union,13 the new legislative framework. The new concept provides the general framework and model conditions for revising existing directives and creating new ones. Further, the market surveillance regulations have been tightened and new regulations for accrediting of conformity assessment bodies have been created.14 The updated New Approach concept comprises the following basic principles: Regulatory Focus 49 • Harmonization is restricted to essential safety requirements and does not go into detail.3 Indeed, due to technical progress and the large number of technical rules, full harmonization would hardly be possible. This system is considerably more flexible than continual revision of the directives. By means of the essential safety requirements, the directives define the desired result with regard to product safety. They do not stipulate the path that has to be taken to achieve that result. • Only products that satisfy the essential safety requirements may be marketed. • The technical details are not elaborated upon in the directives by the institutions of the EU, but rather by the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN), the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation (CENELEC) and the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). This principle of the division of work was introduced for the first time as part of the New Approach.4 • There is a rebuttable presumption that products manufactured in compliance with the harmonized standards satisfy the essential safety requirements.5 • The application of the harmonized standards remains voluntary for the manufacturer. In a legal sense, the requirements of the directive concerned are decisive. The product manufacturers are only obliged to satisfy the essential safety requirements laid down in the directives.6 This opens up to the manufacturer the possibility of manufacturing its product in a way that departs from the harmonized standards, using innovative technologies. That being said, the presumption of conformity as regards compliance with the harmonized standards does not apply here. The New Approach is complemented by the Global Concept of Certification and Testing, 50 July 2009 which addresses the mutual recognition of product tests. Basically, the Global Concept governs the conformity assessment procedure and certification. Meanwhile, since 1987, more than 20 directives have been issued based on the New Approach and Global Concepts, among them the better-known directives on machinery7 and medical devices.8 We must differentiate here between riskspecific (so-called “horizontal”) directives and product-specific (so-called “vertical”) directives. Horizontal directives cover various groups of products that pose a single, specific risk, for example, the low voltage directive.9 Vertical directives refer only to a single product group that poses various different risks. Examples are the Recreational Craft Directive,10 the Lifts Directive,11 the Toy Directive12 and the Medical Devices Directive. Amendments to the Medical Devices Directive Brought About by Directive 2007/47/EC Parallel to these developments, Directive 2007/47/EC15 laid down an amendment to the medical device regulations in EU Member States. The Member States were required to convert the directive into ­national law16 by 21 December 2008 and it takes effect beginning 21 March 2010. The amendments are remarkable in several ways: • Software qualifies as a medical device. • Devices that are also machines within the meaning of Directive 2006/42/EC must also satisfy these requirements. • Not only active implants but also medical devices must, as a general rule, undergo a clinical assessment that can, under certain circumstances, also be taken from the scientific literature. • Repeat evaluations of the clinical tests are to be kept up to date as part of the postmarket clinical follow-up. These obviously new provisions in the directive and the national laws are complemented by many others whose newness may be less obvious. One of these is a change in the conditions applying to the designation of authorized representatives. Changes for Non-European Manufacturers In the old Medical Devices Directive, manufacturers located outside the EU were under an obligation to designate an Authorised Representative within the EU who could exercise the manufacturers’ rights and fulfill their obligations within the framework of the directive. As a rule, this role was undertaken by a consulting firm, which was in a position to assist the manufacturer in the fulfillment of regulatory requirements. According to the new definition set forth in Directive 2007/47/EC,17 the Authorised Representative is “any natural or legal person established in the Community who, explicitly designated by the manufacturer, acts and may be addressed by authorities and bodies in the Community instead of the manufacturer with regard to the latter’s obligations under this Directive.” In addition, Article 13 states: “Where a manufacturer who places a device on the market under his own name does not have a registered place of business in a Member State, he shall designate a single Authorised Representative in the European Union.” These two provisions are currently causing a good deal of uncertainty, not only among companies whose registered offices are outside the EU and who wish to export to the EU, but also among those wishing to market these products within the EU. They beg the question of who is to bear responsibility in terms of product liability law and also from a regulatory point of view, what the repercussions will be if no Authorised Representative has been designated or, for example, if more than one Authorised Representative has been designated. According to product liability law, which is regulated uniformly across Europe, the importer of a product is liable if he cannot, within a certain period, name the manufacturer whose registered office is outside the EU. In addition, the Authorised Representative is liable if he labels the imported products with a brand name of his own. These scenarios, which were already provided for before the amendments to the medical devices directive, now form a volatile mixture. The importer of a medical device is well out of the limelight in product liability terms if an Authorised Representative fulfills the obligations of a non-European manufacturer and the importer can name that individual as the manufacturer’s representative. However, according to the new regulations, if circumstances arise in which no Authorised Representative has been effectively designated, the importer must not expect to be able to pass on liability to the representative or manufacturer. The German Medical Devices Act (MPG) also makes this assumption, as §5 shows: “The person responsible for the first placing on the market of the device is the manufacturer or his/her Authorised Representative. If the manufacturer does not have his/her registered place of business in the European Economic Area and if an Authorised Representative has not been designated, or if medical devices are not being imported into the European Economic Area under the responsibility of the Authorised Representative, the importer shall be the person responsible. The name or the firm and the address of the person responsible must appear on the label or in the instructions for the use of the medical devices.”18 The picture is similar in terms of product safety law. Without the effective designation of a single Authorised Representative, obligations that the Authorised Representative would otherwise be required to fulfill may be incumbent upon the importer, who intends merely to trade in the products. These obligations may include providing information to the market surveillance authorities, or Regulatory Focus 51 participating in the market surveillance system or in measures ordered by the authorities such as warnings or recalls. In all cases, the real raison d’être of the legal concept is to ensure that a contact—in the form of the Authorised Representative—is available in the EU in lieu of the manufacturer. If, however, the appointment of an Authorised Representative is unsuccessful, the consequences for all those involved in terms of product liability and product safety law are obvious. At present, this situation is particularly likely to crop up in relations with Turkey. Turkey is not yet a member of the EU or the European Economic Area (EEA), but it has bound itself to the provisions of medical products law by means of a treaty of accession19 and certain other laws. Thus, Turkey has enacted a law that implements the subject matter of the Medical Devices Directive. For legislative reasons, Turkey was obliged to adopt a provision under which anyone importing into Turkey required a Turkish Authorised Representative. In principle, this provision served to implement the European regulations, but fell short of actually having any effect—except in interaction with the abovementioned treaty of accession—because Turkey was not yet a Member State. It should be made clear that Turkey intended to allow products that had been imported into the EU via a representative other than the Turkish Authorised Representative to be traded in freely. That being said, because of the lack of clarity in the provisions in the Turkish law and a degree of ignorance of the effects of the treaty of accession, a non-European importer may resort to designating an Authorised Representative in Turkey in addition to the one he has designated for the EU. If he does that, the problems already outlined above connection with the new amendment of Article 11 of the directive may arise. A non-European manufacturer can circumvent these problems if, in spite of access to the Turkish market, it designates exclusively a Central European Authorised Representative to cover both Turkey and the EU. 52 July 2009 References 1. A complete overview is available at www.eg-richtlinien-online.de under Medizinprodukterichtlinie. 2. Council decision of 7 May 1985, O.J. 1985 C 136/1. 3. Kapoor A, Klindt T. “New Legislative Framework in EU product safety law—new market surveillance in Europe.” European Commercial Law Magazine (EuZW). 19:649,650 (2008). 4. Krieger S. “The technical environmental law of the Community according to the ‘New Concept’”. Environmental and planning law (UPR). 12:401 (1992). 5. Klindt T. “Consumer protection by the integration of safety law requirements in the design of appliances and devices.” Consumers and the law (VuR). 16:394,396 (2001). 6. Scheel K-C. “Interpretation of EU directives and the competence of the Commission to decide.” Trade and industry archive (GewArch). 45:129,130 (1999). 7. EC Directive 2006/42 of 17 May 2006, O.J. 2006 L 157/24. 8. EC Directive 2007/47 of 5 September 2007, O.J. 2007 L 247/21. 9. EC Directive 2006/95 of 12 December 2006, O.J. 2006 L 374/10. 10. EC Directive 1994/25 of 16 June 1994, O.J. 1994 L 164/15. 11. EC Directive 1995/16 of 29 June 1995, O.J. 1995 L 213/1. 12. Ibid 5. 13. Decision 768/2008 of 9 July 2006, O.J. 2008 L 218/82. 14. EC Regulation 765/2008 of 9 July 2006, O.J. 2008 L 218/30. 15. To be more precise: European Parliament and Council Directive 2007/47/EC of 5 September 2007 on the amendment of Council Directives 90/385/ EEC on the approximation of the laws of the member states relating to active implantable medical devices and 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices, and Directive 98/8/EC concerning the placing on the market of biocidal products. 16. Following this the German Medical Products Act was amended by the German legislators. The new version is available at http://bundesrecht.juris.de/ bundesrecht/mpg/index.html. 17. Article 1 a III 18. Translation of this paragraph copied from www. bmg.bund.de. 19. Resolution 1/95 of the European Commission. Author Philipp Reusch is a founder and equity partner of the international commercial law firm Reusch Rechtsanwälte GbR. He has published widely, including the Handbook of Product Liability and lectures at Cologne’s University of Applied Sciences on product liability law. Reusch can be reached at p.reusch@ reuschlaw.de.