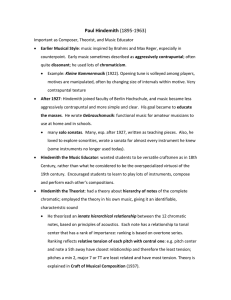

Early Music Influences in Paul Hindemith`s Compositions for the Viola

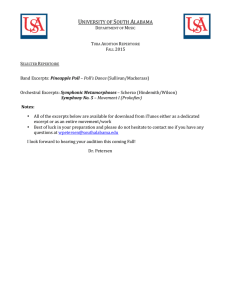

advertisement