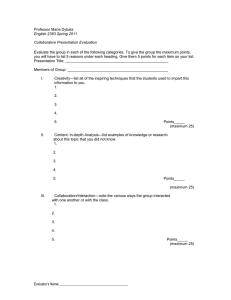

A Project Manager`s Guide to Evaluation

advertisement