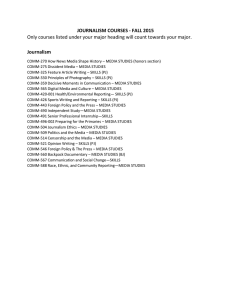

We Media | How audiences are shaping the future of

advertisement