63 pages

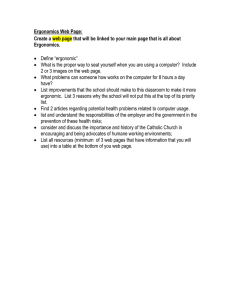

advertisement