ALLAIN, RHETT. Investigating the Relationship Between Student

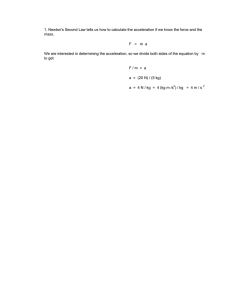

advertisement