cultural universality versus particularity in draft

advertisement

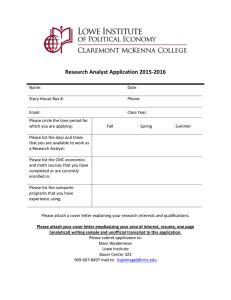

CULTURAL UNIVERSALITY VERSUS PARTICULARITY IN CMC DRAFT Bernd Carsten Stahl De Montfort University, Leicester, UK bstahl@dmu.ac.uk Ibrahim Elbeltagi Wolverhampton University, Business School i.elbeltagi@wbs.wlv.ac.uk Abstract: Cultural factors are often identified as a crucial influence on the success or failure of information systems in general and computer-mediated communication (CMC) in particular. Several authors have suggested ways in which management can accommodate these factors or solve the problem they pose. This paper attempts to go one step beyond management measures and ask whether there is a theoretical foundation on which one can base the mutual influence of culture and CMC. In order to find such a theoretical basis the paper discusses the question whether there are aspects of culture that are universal or whether culture is always particular. In the course of this discussion the concept of culture is defined and its relationship with technology is analysed. As a solution the paper suggests a Habermasian approach to culture which sees a universal background to particular cultures in the structure of communication which creates and sustains culture. The paper then tries to give an outlook how such a Habermasian theory of culture can enable designers and users of CMC to reflect on their activity and improve the quality and reach of CMC. Key words: Culture, computer-mediated communication, ICT, Habermas, universality, particularity 1 INTRODUCTION Culture is frequently named as a determinant of usability of computers. That means that the culture from which a developer, programmer, or user stems makes a difference regarding whether she is willing or able to use a certain technology. This is a robust and tenable assumption given that it is common knowledge that the success of information systems depends on many "soft" factors and the term "culture" is often used to describe some of these. However, it is also a questionable assumption when one considers that in principle all humans can interact and computers as the "malleable" technology can be customised to uses in most cultures. The problem therefore seems to be one of delineation. Up to what point do different cultures diverge and what, if anything, do they have in common? This is of interest because an answer would inform us of what analysts and designers of information systems can take for granted independent of their target culture and what parts of the systems would have to be customised or even reconceptualised. The aim of this paper is therefore to analyse whether there is a clearly demarcated part of human culture that is universal to all cultures and, if so, what this means for computer-mediated communication. In order to be able to answer this question the paper will begin by taking a look at the meaning of the term "culture. The paper will look at different definitions of culture and discuss the two principal views that culture is either universal or particular. In a subsequent step the relevance of this question to computer-mediated communication is discussed. It will become clear that the same question of universality versus particularity of culture can be found concerning CMC. As a solution to this problem it is suggested to apply the Theory of Communicative Action by Jürgen Habermas. This theory recognizes the factual plurality of cultures but emphasizes the fundamental underlying constant which consists of human beings and 2 the universal structure of their communication. Finally, the implications of this approach for CMC are discussed. It will be suggested that despite pervasive cultural differences there are universals in the communication which constitutes culture. These universals can be used as starting points for the design and use of CMC with the purpose of facilitating cooperation, which will be demonstrated using a comparative study of the use of decision support systems in Egypt and the UK. CULTURE In order to determine whether the universality of culture - or lack thereof - have something to contribute to computer-mediated communication the first step should be the definition of the term. The first part of this section will therefore be dedicated to the description of several different views of what the term "culture" might in fact mean. The second part of the section will then discuss whether these definitions of culture allow us to draw a conclusion as to its universality. Definition of Culture For the purposes of this paper there are two dimensions of culture that are of relevance. One is the culture that a society shares, the other one is culture on a smaller level, namely organisational or corporate culture. Both of these dimensions share several aspects and refer to one another. Cultural studies usually aim at describing the macro-level of society. Here, culture can be defined as the quintessence of the physical resources and perceptions, of the physical and mental techniques which allow a society to persist (cf. Gehlen 1997, 80f). Culture thus consists of facts, artefacts, institutions etc. but its most important function is that of a reservoir of shared interpretations and collective experiences (cf. Robey & Azevedo 1994). "Culture, at its most 3 basic level, can be conceptualized as shared symbols, norms, and values in a social collectivity such as a country." (Walsham 2002, 362) The process of sharing and thus constituting reality that culture implies is based on communication (Wynn, Whitley & Myers 2003). Communication, as Castells (2000, 403) points out, is based on the production and consumption of signs. These signs are the way in which humans understand their world and they can thus be said to constitute reality. The reliance of culture on signs as a means to interact is a fact that can be observed on the societal as well as the organisational level (Ward & Peppard 1996). For the question of the influence of culture on CMC the aspect that seems most important is the sharing of interpretations. Communication as the basis of culture is only possible given the assumption that the participants share some experiences in order to be able to communicate at all. To a certain degree, a shared culture is thus necessary to communicate but at the same time it is also the result of communication. Culture is thus the basis and the result of a self-referential process. This process defines what is perceived as natural and normal, it defines the way things are. In this sense culture is enormously powerful because it shapes reality. It contains not only the facts of a society but also its aspirations, its shared utopia (Bourdil 1996). That means that it has a strong normative aspects because it contains and justifies the accepted morality and the permissible ethical theories. "The concept of culture is a value-concept" (Weber 1994, 71). This normative side of culture can also produce problems. The agreed-upon utopia of a society may be a bad one in the sense that it endorses values that are objectionable from the point of view of other cultures, such as racism or totalitarianism (French 1992). Furthermore, if the power of definition in a culture becomes rigid and encrusted then it can also turn into an ideology, a fact that is emphasised by cultural criticism and ideology critique (Schultze & Leidner 2002). 4 Another aspect of culture that is important in the context of CMC is the culture of an organization. As already noted, this type of culture is closely linked to the meta-level of societal culture but also slightly different from it. Corporate culture can be defined as "commonly shared values which direct the actions of the employees towards the common purpose of the enterprise […]. Corporate culture understood as the totality of existing and practiced values, forms the moral basis of all corporate activities" (Steinmann 2001, 11). Corporate or organizational culture fulfils the same role in an organization that culture fulfils in society. It defines what is real, what is important, and thus how one should act. This has led to an extensive use of the term as a vehicle of business ethics. This importance of organizational culture has at the same time led to some problems and misunderstandings. If culture is central to an organization's perception of and interaction with the world then it is clearly in the interest of management to control and manage it (Ward & Peppard 1996; Robey & Azvedo 1994). However, if culture is the basis of the understanding of the world then it is questionable in how far such an instrumental use is possible. Furthermore, given the ethical nature of culture it is also doubtful whether management of culture is desirable or morally admissible. Also, there remains the open question of the guidelines according to which organizational culture is to be managed and maybe improved. All of these questions have an impact on how technology can be used. They show that culture is an important variable in CMC. So far it remains open, however, whether culture is really a useful variable in this context or whether it is an umbrella term used to collect aspects that are otherwise incommensurable. An important part of the answer to this question depends on whether there is something that all cultures share, which would mean that culture is partially universal, or whether different cultures are fundamentally different and particular. 5 Universality versus Particularity of Culture There are undeniably different cultures on a societal as well as an organisational level. Given this fact one can ask the question how deep the differences run. In this paper we will distinguish between two possible answers to this question. The proponents of particularity of culture on the one side believe that different cultures are fundamentally and possibly irreconcilably different, whereas the proponents of universality believe that all cultures share some universal attributes. These two ideal-typical positions appear in reality in different shades of grey. For the purposes of this discussion we will attempt to portray them as unequivocal as possible. The particularist interpretation of culture says that different cultures differ in all possible ways and that there is nothing that binds them together. This means that the sense-making function of culture is limited to the members of a certain culture and sense and meaning may not be translatable from one culture to another. If this is correct then the meeting of different cultures will lead to misunderstandings and frequently to conflicts. On a global scale this scenario has been proposed by Samuel Huntington’s thesis of the "clash of civilisations" (Huntington 1993). Another indicator that could be taken to mean that cultures are irreconcilably particular is that of morality (French 1992). We have seen that moral norms are an integral part of cultures. A look at existing moralities shows that they are often diametrically opposed. Some cultures believe in the sanctity of life, others in capital punishment. Some believe in forgiveness, others in retaliation. There are head-hunter and cannibal cultures as well as cultures that promote peace and forgiveness. The universalists on the other hand concede that there are factual differences between cultures but contend that these are limited and that there are underlying commonalities. The possibly most important argument for this viewpoint is that despite the differences in cultures there has always 6 been exchange of goods and ideas between different cultures. If this is possible, they would argue, then it means that people can share meaning and their life-worlds, albeit in an imperfect way. However, it means that translation of language and meaning is possible, which, in turn, indicates that culture as the carrier of language and meaning should have universal aspects. This argument is strengthened by the social development that is often called "globalisation". Several authors emphasise that globalisation means that different cultures become more similar, or may even merge to a certain degree (Beck 1998). The international and trans-cultural use of information and communication technology that is the centre of this paper is just one example for this. If one agrees with this univeralist view the next question is: what is it that is universal to all cultures? One possible answer that will be the basis of the further argument of this paper is that what all cultures have in common is their nature as social constructs and the fact that they originate from human beings. The commonalities of all cultures are thus based on the commonalities of all humans. Universalism of culture is a result of anthropological constants. Among these anthropological constants we can find the fact that humans live a self-formed and technical environment (Gehlen 1997). Not only do humans collectively build cultures but they also require a cultural background to develop an individual and collective identity (Castells 2000). Also, there are several existential similarities between all humans that affect our cultures. Among them there are our bodily and fragile existence and the fact that we face death and know about it. The conclusion in this paper is that, despite obvious difference in cultures, there are similarities that are based on human nature. Before we can proceed to the question how these cultural 7 commonalities relate to computer-mediated communication, we will analyse the state of the discussion concerning the influence of culture on CMC. CULTURE AND CMC Having introduced the discussion regarding particularity versus universality of culture in general terms this section will be dedicated to the influence of culture on CMC. In the first step it will look at the relationship of culture and information and communication technology (ICT) in order to then proceed to the influence of culture on CMC in a narrower sense. The chapter will end by reviewing the arguments for and against universality of culture in CMC. Culture and ICT Information technology is always incorporated into social practices without which it would be useless. Information systems as the study of ICT in organisations, for example, tends to explicitly recognise social and cultural processes as part of its research object (Lyytinen & Hirschheim 1988). There is a mutual influence between ICT and culture and we will first look at the influence of ICT on culture and then turn our view to see what influence culture has on ICT. Many texts concerning the impact of ICT on culture tend to concentrate on corporate culture and here on the relationship between ICT and organizational change. Organizational change affects organizational culture and, in order to be successful, must be supported by a culture that allows change. ICT is frequently seen as a driver and facilitator of change. However, there is no clear relationship between change and ICT. ICT has a certain "interpretive flexibility" (Robey & Azevedo 1994, 32) which allows it to be used by most parties and for most purposes. 8 The change in the organization that ICT may bring about can lead to more flexibility, for example in working hours (Himanen 2001), but also to less flexibility, for example through electronic surveillance. A similar argument can be made for the influence of national culture on social change. ICT can thus lead to change that will affect culture but at the same time the prevailing culture can also affect ICT. Culture in the sense of a meaning-constituting horizon of the collective life-world determines the perception and use of ICT. This is again true for the organizational level where culture can influence whether employees are able and willing to use certain technologies. It is also true on a societal level where culturally based perceptions have some bearing on the use of ICT. A national culture that emphasizes sharing and the collective, for example, will lead to different uses of ICT than one that emphasizes the individual and competition (Raboy 1997; Riis 1997). Culture and CMC Before the background of the mutual influence of culture and ICT we can now proceed to look at the relationship of culture and computer-mediated communication. It is important to keep in mind our central research question, namely the problem of cultural particularity versus universality, which is supposed to help us eventually determine how the cultural aspect can be taken into account in the design and use of ICT. Computer-mediated communication here stands for the use of information and communication technology for the purpose of exchanging information. There are two technologies that are the typical representatives of CMC: the Internet and email. These are widely used today and they are also researched quite extensively (Agarwal & Rodhain 2002). The characteristics of CMC are 9 often such that it is situated between or beside traditional forms of communication. Email communication, for example, is neither exactly like spoken language but it is not directly comparable to written language either (Kolko 2000; O’Leary & Brasher 1996). There is a multitude of different interactions between culture and CMC. These interactions are not linear or predictable. Different applications of CMC "change the way people interact; they generate whole new functioning institutions. Like the market or democracy, these innovations have a life—a social evolutionary dynamic— of their own" (Danielson 1996, 70). However, it is not always clear how and in which direction these changes develop. The reason for this is that CMC reflects the culture in which it is used (Castells 2000). The same technology can thus be used for different ends in different contexts. CMC also influences other parts of culture in different ways. One of the cultural areas where ICT has a huge influence is that of ethics. We have seen before that ethics and moral norms are an integral part of all cultures. These norms are affected in different ways by the use of computers. Examples of this could be the changing quality of communication. CMC tends to concentrate on written communication and neglect the non-verbal part, which, according to some observers, carries the majority of meaning. Another problem might be the invisibility of the other as a human being behind technology. Some ethical theories emphasize the other and our recognition of the other as someone similar but different from ourselves as a central part of ethics (Ricoeur 1990; Levinas 1983; van den Hoeven 2000). Other moral aspects of CMC could be the effect it has on our perception of gender (Herring 1996), privacy (Kolb 1996) or a host of other moral problem. 10 Universality of Culture and CMC Having argued that there is a close link between CMC and culture the next step in this argument is to check whether the influence of culture on CMC is universal or particular. Not surprisingly, the same arguments about universality versus particularity of culture that were outline above can be found here again. On the one hand there is the universality argument which is supported by the fact that ICT has a world-wide reach and appears to be used in similar ways independent of the prevailing culture. The prime example here is clearly the Internet which not only seems to be culture independent but may even produce a new universal world-wide culture. On the other hand one can find the argument that this apparent universality of technology and its accompanying culture is just a deception and that the cultural differences run deeper. It has been argued that the homogeneity of technology use is not based on cultural universals but instead on cultural imperialism. This sort of argument contends that the uniformity of technology is not natural but the result of the application of power with the aim of creating big markets (Weckert 2000). Another example is that of e-government and e-democracy which is among the high promises of CMC but which does not progress uniformly in different cultures (Ess 2002). Similar observations have also been made on an organisational level. The cultural context determines the usability of CMC, for example by favouring certain types of communication over others. Ess (2002b) mentions that the ratio of content to context in communication or the status of anonymity which differ between cultures and affect CMC. 11 HABERMASIAN CULTURE AND CMC In this section we will give a brief description of a theory of culture from the point of view of Habermas theory of communicative action. In a second step we will then analyse what this can mean for CMC and whether it can help the design and use of ICT. A Habermasian View of Culture So far we have established that culture and CMC are intertwined in a complex relationship and that both sides of the universal versus particular debate have good arguments. In order to overcome the apparent contradiction between the two positions we suggest a Habermasian view of culture that would allow the simultaneous admission of cultural pluralism and universalism. Briefly, this theory is based on Habermas (1981) theory of communicative action which holds that our reality is shaped by discourses. These discourses consist of arguments concerning contentious validity claims. Every speech act contains at least three validity claims, namely truth, legitimacy, and authenticity. Whenever the claims of a speech act are doubted, the affected parties are called upon to clarify them in a discourse. Discourses are acts of communication that are characterised by the fact that they emulate the ideal discourse in which there would be no distortions due to power differences, different abilities etc. and where only the better argument would count. The result of such discourses would be a consensus about the validity claims which would then constitute part of the shared life-word of the participants. In terms of this paper that means that discourses constitute culture, that they are the resource that produces the collective knowledge, values and perceptions that we defined as culture. In Habermas theory there is a close relationship between culture, society, and person (Habermas 1998). In this framework it is not problematic to concede that there are different cultures that 12 affect our use of technology. Different people have different life-worlds and different cultures can develop according to different perceptions. However, there are universals combining these particularities and that constitute cultural universals. The first universal is that all humans have a culture and that culture is a constitutive part of personality. Second, the way a culture is formed by discourse is universal. While discourses deal with different matters, their structures and the fact that they are built upon validity claims is universal. The Impact of Habermas’ Theory of Culture on CMC A Habermasian view of culture can support the use and development of CMC in different ways. There are theoretical considerations as discussed above. They help overcome the apparent dichotomy of universality versus particularity of culture by offering a way of seeing the universal in the particular. By opening this view, the Habermasian understanding of culture firstly sharpens the attention to culture and secondly points towards ways of incorporating cultural factors in CMC. Different cultures can be understood as different voices in a discourse and different cultural perceptions can be interpreted as validity claims. The intercultural differences concerning validity claims can then be taken as a starting point of discourses. At the same time, the Habermasian understanding of how discourses shape culture and thus reality can help us design technology used for communication. First, one should realize that culture is a necessary background for all understanding and all technology and that it cannot be used in a strategic manner. Management may try to shape organizational culture but this is only possible in a very limited way. It is impossible to predict the exact way in which culture and CMC will interact. 13 However, the structure of communication and validity claims outlines principles that are valid for CMC just as for every other type of communication. While the actual validity claims that interlocutors can make in the course of communication or a discourse are not predictable, the type and relevance of these claims is known. Independent of who says what about which subject, there will be claims of truth, legitimacy, and authenticity involved. Furthermore, in order to gain acceptability it must be possible to question these claims and exchange arguments about them. This is the area where CMC designers can take quite direct cues from Habermas’ theory. An important one of these cues is that the validity claims that constitute communication are always connected. That means that the distinction of truth, legitimacy, and authenticity is useful for analytical purposes but real communication contains all of them simultaneously. Every speech act contains them either explicitly or implicitly and the validity of one claim cannot be completely distinguished from the others. This is relevant because it underlines that the attempt to use ICT as a means of transmitting "objective" truth claims in the form of data is doomed to failure when it neglects that truth always must be legitimate and reflect on the speaker. This is what many IS researcher who use the Foucault’s theoretical framework point out when they speak about power and knowledge, about regimes of truth. Unlike the Foucauldians, for whom truth remains particular, the Habermasian approach allows the identification, if not of truth, then of the legitimate way of determining truth. Our Habermasian approach has so far informed us that beneath all of the cultural particularities and peculiarities there exists a universal structure of communication. The question that needs to be answered is, how should we deal with differences and how can these insights help us improve the design and use of technology for communication? The answer lies in Habermas’ central construct of discourse. While validity claims and their cultural expressions differ, these 14 differences can be addressed by establishing discourses. In Habermas’ theories discourses appear in at least two places. On the one hand there are real discourses in which affected groups and people discuss factual validity claims. On the other hand there is the ideal discourse in the ideal discourse community which functions as the ideal that real discourses need to emulate in order to come to acceptable conclusions. Both of these functions, real and ideal discourses can help us in CMC. How this can be done is a question that will be discussed in the next section. CONSEQUENCES OF THE ADOPTION OF A HABERMASIAN UNDERSTANDING OF CULTURE What is the practical value of these considerations? This section will briefly outline which consequences the adoption of the Habermasian idea of culture can have in research and practice of information systems in general and CMC in particular. A word of caution is in order, however, before we proceed to these applications. Our understanding of culture is implicitly given before any type of intercultural research or practice can be realised. To stay within the Habermasian framework, one can say that our understanding of culture is part of our individual and collective life-world. As such it is always presupposed, even though it can of course be questioned. When it is questioned, it is always affected because it needs to be rethought and justified. This may change our view of culture and thereby part of the cultural reality that we as researchers or practitioners constitute. A view of culture is thus transcendental (in the Kantian sense) for research on culture. That means that a particular understanding of culture is a necessary condition of the possibility of doing research on culture. An independent observer’s position on these questions is thus impossible. This leads us in rather deep philosophical waters. How can one do research on transcendental entities? How can they be used in organisational practice? The following sections will outline some ideas concerning these questions. 15 Research on Culture and CMC The description of culture as transcendental shows that it does not lend itself to simple research designs. Positivist research about culture is of questionable value in this framework. Given the shared life-world of which the researcher is a part, there is no independent reality in which cultural understanding could be observed. It is thus impossible to "test" whether the theories developed here are correct. For testing them, one would have to assume a position on their correctness, which again rules out an independent observation. The researcher is always part of the creation and interpretation of culture. Research on culture and CMC will always affect its research object and is thus only possible as part of the hermeneutic cycle (Gadamer 1990). This is not problematic as the necessity of hermeneutic reflection is well recognised within non-positivist research in IS (Myers & Avison 2002). Within the non-positivist research that remains open to the researcher, some alternatives seem particularly well-suited. The Habermasian framework states that all communicative acts contain descriptive, normative, and performative aspects. A researcher adopting this framework would have to take serious that the research itself interferes with research object’s view of the world, of themselves and their ethical rights. The object of research, the person or group using CMC in a particular cultural setting, should be recognised as a person (or group of persons), which means that the researcher needs to take them seriously. But even more, the researcher should use his or her advanced knowledge to engage with the object to help improve their lives. This includes open and honest communication. Researchers must recognise the social responsibility they have because of their role as researchers and should strive to make a positive difference. This means that using the Habermasian framework indicates that the researcher should engage in critical research. Critical research aims to improve the speech situation, to "unmask and critique the 16 forms of domination and distorted communication by showing how they are produced and reproduced" (Schultze & Leidner 2002, 217). Furthermore, the research will aim to emancipate the research objects, which allows them to take their part in discourses (Ulrich, 2001; CecezKecmanovic 2001). This turn toward critical research will not be a surprise to those readers familiar with Habermas’s work. He is considered one of the most prominent representatives of the "Frankfurt School" of philosophical thought, which explicitly aims to promote critical research. When one looks at examples of Habermasian research in the field of Information Systems, one can find reflections of this critical interest (cf. Lyytinen & Hirschheim 1988; Hirschheim & Klein 1989; Hirschheim & Klein 1994; Klein & Myers 1999; Hirschheim & Klein 2003). This is not to deny that critical and emancipatory intentions sometimes clash with other roles and duties of the researcher (Howcroft & Wilson 2003). Nevertheless, research based on Habermas’s theories attempts to expose inequalities in discourses and attempts to emancipate the research objects. Examples of such research concerning CMC or information systems can be found in the area of politics, where a Habermasian framework is often used to describe the shortcomings of technical solutions in egovernment or e-democracy and formulate solutions (Ess 1996; Kolb 1996; Heng & de Moor 2003). Democratic processes are similar to discourses and are based on related assumptions. One can interpret democracy as a realisation of discourses (Habermas 1998) which means that Habermasian ideas can be used to judge the quality of e-government or e-democracy. Other pieces of critical research using Habermas’s framework have looked at teaching and the use of technology in an educational environment. Education can be seen as providing students with the means to participate in discourses (Settle & Berthiaume 2002), which renders Habermasian ideas immensely useful. 17 Practical Relevance of a Habermasian view of Culture In a globalised world where most large companies and many small and medium sized businesses are active on an international scale, the question whether cultural assumptions are universal is of great importance. This leads us back to the starting point of the paper. How can a company know whether its information systems are universally useful or how can a systems designer find out whether a specific part of the design is going to be successful in different cultural contexts? The Habermasian framework discussed here does not give simple algorithmic solutions to these questions. However, it does indicate how practical issues can be addressed. In order to consider how the differences between cultures can be addressed and the discursive framework put into practice, we need to go back to the two functions of discourses. Discourses are theoretical entities that describe the ideal discourse situation one should aim for but at the same time they are real social processes. Both aspects of discourses can give us indications of how to act. First, let us reflect on real discourses. In order to overcome cultural particularity, CMC should allow the users first of all to express their validity claims clearly. These validity claims, in order to gain interpersonal validity, must be questioned. If CMC carries validity claims, then this means that it must allow for the critical discussion of these claims. This is a central problem of many information system because they incorporate and are based on particular assumptions that are on the one hand hard to identify and on the other hand even harder to change. In order to allow intercultural communication and facilitate general use, CMC must therefore be of a flexible nature and allow for unforeseen criticism. A second conclusion to be drawn from real discourses is that it is important to allow those parties that are affected to have a voice in the discussion of disputed claims. This stakeholder approach has an ethical background (Donaldson & Preston 18 1995) but has also been shown to be useful for straightforward questions of systems design and project definition as described by Metcalfe & Lynch (2003). Second, the idea of the ideal discourse and the ideal discourse community can serve as guidance in the design and use of ICT. If stakeholder discourses are to be facilitated then it is important to do so in such a way that the results are acceptable. This means that the distortions that are always part of real communication are minimized. CMC should emulate the possibilities of communication that are given in real communication. There are interesting approaches that try to visualize the frequency of CMC use, for example, which will give participants an idea of the status of speakers (Erickson et al. 2002). The idea of this and similar applications is to overcome the traditional weaknesses of CMC by giving participants additional information about discourses. In a face-to-face setting we implicitly have a large amount of information that is not part of the explicit discourse. We know who speaks and how long. We have a feeling of who interacts frequently, who tends to dominate discourses, or who makes useful comments. Technology can be used to approximate this knowledge and thereby make its own use more transparent (Smith 2002). The examples mentioned here use visual tools to show how often individuals have participated in communication or which impact on communication a participant has. This allows participants a better understanding of the discourse itself and thus helps approximating the Habermasian ideal discourse in the computer-mediated communication. These are just some examples of how technology can be used to move CMC closer to ideal conditions of discourse which can be seen as universal and culture-independent. These examples might suggest to the reader that the theoretical approach can be used in a straightforward way to solve organizational problems. This view overlooks the critical impetus of Habermasian theory. Just like it requires the researcher to reflect onto his or her role and choose a 19 critical approach it also requires the practitioner to take the wider implications of his or her actions into consideration. This means that the user or developer of a CMC technology needs to consider the non-technical implications, the ethical rights and obligations, the ability of others to use this technology to improve their participation in discourses. A purely purposive-rational use of technology which only looks at a narrow set of (usually economic) goals is ruled out. This should not be misunderstood to mean that business considerations should be neglected, but they are just one set of factors to be reflected among others. A Habermasian understanding of culture is thus not practical in that it allows designers and users of CMC to follow clear rules to overcome intercultural differences. It is practical, however, in that it shapes our understanding of culture and its influence on the use of technology. This understanding, in turn, allows designers and users a better and critical understanding of the impact of their activities. Such a critical view of one’s activities then opens up new dimensions of perception and thereby new avenues of action. Decision Support Systems in Egypt and the UK: an Example In order to illustrate the arguments of this paper, we will now briefly present some empirical evidence from our research. The starting point of this research was a review of the literature that indicated culturally-based differences in the use of Group Decision Support Systems. From studying the transfer of IT to the Arab world, Straub et al (2001) suggest that specific components of Arab culture have an influence on how IT is viewed and the extent to which it might be utilised. The research aimed to compare the use of decision support systems (DSS) in local authorities in Egypt and the UK (El-Beltagi, 2002). The study can serve as an example of some of the aspects 20 raised in this paper because it looks at the use of similar technologies in two very different national cultures. Furthermore, DSS can be seen as a good example of several of the aspects of CMC because they rely on and facilitate communication between different stakeholders in order to come to a decision, which is a traditional task of discourses. The study was based on the use of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1993) but it went beyond typical TAM research by identifying the similarities and differences between the two cultures regarding the use of DSS in strategic decision making in local authorities and the problems that they encounter. The research used both quantitative and qualitative data. Data was collected from 294 and 70 CEOs and IT specialists from both Egypt and the UK. One can very briefly contrast the British and Egyptian culture as follows: In the UK, the history of individualism and utilitarianism as well as a general belief in the scientific exploration of reality give rise to a rational bureaucracy as described by Weber (1947). Private property enjoys high status and recognition. Organisations are expressions of individual preferences and as such legitimised. Decisions are to be made objectively and technology can help decision makers do this. DSS are thus in principle acceptable and desirable tools. In Egypt the approach to organisations is less structured and formal. Decision makers rely more on intuition and are more embedded in their social environments. Decisions are made on the basis of background knowledge and intuition. They are oriented towards social expectations rather than detached rationality. Given these differences, it is not surprising that DSS use in local authorities differs significantly between the UK and Egypt regarding the problems that they encounter. As indicated by the following figure, the three most severe categories of problems are the problems related to the availability of trained DSS staff and decision-maker (mean score 43.52), environment-related 21 problems (mean score 36.65) and managing the process of DSS implementation problems (mean score 53.083) in the Egypt group, while the three most severe categories in the UK group are the top management problem (mean score 37.97), the problem related to the availability of trained DSS staff and decision-makers (mean score 32.66) and environmental related problems (mean score 28.35). mean severity score in Egypt mean severity score in UK data related problems top management problems DSS characteristics related problems organizational related problems managing the process of DSS implementation problems Environmental related problems 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 trained DSS staff and decision-maker problems Score Severity of problem category in Egypt and UK Problem category Figure 1: Severity of problems comparison between Egypt and the UK The study also indicated a significant difference in all the dimensions of the national culture according to the Hofstede criteria between the two research groups. What is of interest for this paper is whether the theory developed so far can help us see commonalities underlying the different cultures. It was suggested earlier that communication as a human constant as well as the necessary existence of validity claims within all speech acts, 22 including those mediated by technology, are common factors independent of culture. The question is thus: can we find validity claims that are accepted in one culture and not in the other? And can we use the theory of culture put forward in this paper to help overcome the problem of contentious claims? Cultural differences are in many cases quite easily reduced to diverging life-worlds based on diverging validity claims. Habermasian speech acts contain claims to truth, normative legitimacy, and authenticity. Our research produced examples of all three claims being evaluated differently in the UK and Egypt. The scientific and formal-rational understanding of systems in the UK allows participants to accept results of DSS and to take them for granted. In Egypt, however, comparable truth claims by DSS require more support and are not taken at face value. As one Egyptian head of city said: "I am not ready to use the DSS in [decision making] until I have enough experience with it and I see how accurate the data is". This reluctance to accept the results of DSS is based on a culturally supported scepticism towards technology. This does not mean that the Egyptians are generally unwilling to use technology. Due to a lower level of familiarity with technology, however, a special emphasis is placed on training. This is where the next cultural difference in the acceptance of validity claims becomes obvious. In the UK, training is meant to convey specific skills and the legitimacy of the training content depends on the qualification and organisational link of the trainer. This individualist approach is less acceptable in Egypt where the social status of the trainer is relevant for the legitimacy of training. As a head of a city council stated: "[] if anyone is going to train me […] it is better to be an experienced head of city council who has used the system". This also implies a lack of acceptance of the third type of claim, the claim of authenticity. By stating that those lower in the hierarchy are not 23 sufficiently trusted, the respondents also indicated that they doubt their knowledge (truth claim) or authenticity. This list of examples could easily be extended. We will refrain from doing so because of space restraints. It should have demonstrated, however, that cultural differences impacting on technology use are based on underlying similarities in the structures of communication. How could a researcher using our framework use this to his or her advantage? As suggested earlier, real and ideal discourses can be of help here. Real discourses are needed to clarify implicit validity claims and to challenge them. They require the input of those affected which means that in the above example, city leaders would have to incorporate the vendors, trainers, users, etc. in order to achieve acceptability of systems. Similarly, decision makers who deploy systems need to use discourses in order to create acceptance for their deployment decision. A frequently raised concern was that people did not know why they should use DSS. They suspected political reasons for their use, which they did not agree with. Real discourses allow the discussion of such concerns. The idea of the ideal discourse and the ideal speech situation could also be applied in our example. Its purpose is to describe how discourses should be structured in such a way as to be maximally acceptable. This means that they should be open to all affected parties and that these parties should be able to voice their opinions without obstacles. On the one hand this means identifying stakeholders and on the other hand, it aims at facilitating a power-free discourse. This can be translated in organisational and institutional arrangements. It can also be transferred to the design and structure of the system. In our case, this might mean that the users of the DSS should be able to drill down to how decisions are structured, who inputted data, which decision and inference rules are used, which weightings of which factors were made and by who. This would 24 allow those users who doubt the truth claim of a system to track the bases of the claim and specify the reason for their mistrust. The system might also allow for the institution of discourses regarding contentious claims. This example should have demonstrated the validity and some possible applications of the Habermasian theory of culture. Its limits are that it applies a theory to data which was originally geared toward a different research question. Some of the specific strengths of our approach are thus not reflected. In a further step one could use the communicative theory of culture to demonstrate the role of the researcher in the results of his or her research. This should then lead to a critical way of dealing with the research subject and the explicit reflection of moral or ethical issues. CONCLUSION In this paper we have tried to show that culture is of high importance for the design and use of ICT and CMC. This importance of culture is reflected by the fact that the successful use of CMC depends in large parts on the underlying societal and organisational culture. Given the obvious differences between cultures the paper has tried to find out whether there are cultural universals that allow the determination of general principles of design and use. Using a Habermasian framework, we argued that there are cultural universals that are based on the anthropological constant of communication and the universality of validity claims. We have tried to show that from such a Habermasian framework one can draw conclusions concerning the actual use of ICT. The paper is mostly conceptual and tried to show that Habermas’ work is relevant in CMC. It briefly reviewed consequences for research and practical applications or examples. The conceptual approach distinguishes it from other research in culture and ICT / business such as 25 Hofstede’s or Trompenaar’s. Such traditional research on culture must make implicit assumption regarding the universality of culture but rarely reflects on it. Hofstede, for example, implicitly states that his criteria of different culture such as power distance or the difference between masculinity and femininity are universally applicable. This is an assumption whose truth value is not simply obvious and which can be debated in the light of this theory. As a final remark we want to point to the limits of this approach, which have been hinted at during the section on the practical relevance of the theory. A Habermasian concept of culture can be used to draw conclusions regarding the use of ICT. However, one should keep in mind that in a way this inverts the relationship of culture and ICT. Technology is always embedded in a greater cultural setting and it is meant to serve communication that is used to create and maintain this culture. This precludes us from an instrumental use of culture and shows that technology is just one possible solution to some problems that arise in society. The question of cultural universality versus particularity is one that has an impact on CMC but it goes far beyond it. Questions of cultural universality have political, social, and ethical implications and the use of technology in this context carries the danger of turning into cultural imperialism. Furthermore, the use of a theory of culture to facilitate CMC carries the threat of turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy (Johnson 2001). In order to understand culture, to understand and accept cultural differences, and to overcome them where necessary, CMC and information systems can only be a minor tool. What is more important is an awareness of the problem and a willingness to accept cultural differences. One important approach to this will be education (Ess 2002b; O’Leary & Brasher 1996). The topic of this paper should thus be understood as a part of the greater question of how we should deal with 26 different cultures. The question of CMC and culture should thus be seen in context and understood as an important but dependent aspect of a greater discourse. REFERENCES Agarwal, R. & Rodhain, F. "Mine or Ours: Email Privacy Expectations, Employee Attitudes, and Perceived Work Environment Characteristics," Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, Hawaii, January 7-10, 2002 Beck, U. Was ist Globalisierung? Irrtümer des Globalismus - Antworten auf Globalisierung. 5th edition, Frankfurt a. M.: Edition Zweite Moderne, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1998 Bourdil, P-Y. (1996): Le temps. Paris: ellipses / édition marketing Castells, M. The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Volume I: The Rise of the Network Society. 2nd edition Oxford: Blackwell, 2000 Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. "Critical Information Systems Research: A Habermasian Approach" in: Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Information Systems, Bled, Slovenia, June 27-29, 2001, pp. 253 - 263 Chapman, G. & Rotenberg, M. "The National Information Infrastructure: A Public Interest Opportunity, " Johnson, D. G. & Nissenbaum, H. (eds.), Computers, Ethics & Social Values. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1995, pp. 628 - 644 Danielson, P. "Pseudonyms, MailBots, and Virtual Letterheads: The Evolution of ComputerMediated Ethics," Ess, C. (ed.) Philosophical Perspectives on Computer-Mediated Communication. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996, pp. 67 - 93 Davis, F. D. "User Acceptance of Information Technology: Systems Characteristics, User Perceptions and Behavioral Impacts," in: International Journal of Man-Machine Studies (38:3), 475 - 487 Donaldson, T, & Preston, L E, "The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications," in: Academy of Management Review 1995, Vol 20, No 1, pp. 65 - 91 El-Beltagi, I, The Use of Decision Support Systems in Making Strategic Decisions in Local Authorities: A Comparative Study of Egypt and the UK, Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, University of Huddersfield Business School, 2002 Erickson, T et al., "Social Translucence - Designing Social Infrastructures that Make Collective Action Visible," in: Communications of the ACM (45:4), 2002, pp. 40 - 44 Ess, C. "Computer-mediated Colonization, the Renaissance, and Educational Imperatives for an Intercultural Global Village," Ethics and Information Technology (4:1), 2002, pp. 11 - 22 27 Ess, C. "Cultures in Collision: Philosophical Lessons from Computer-Mediated Communication" Metaphilosophy (33:1/2), Special Issue: Cyberphilosophy: The Intersection of Philosophy and Computing. Edited by J.H. Moor and T.W. Bynum, 2002b, pp. 229 - 253 Ess, C. "The Political Computer: Democracy, CMC, and Habermas", in: Ess, C. (ed.) Perspectives on Computer-Mediated Communication, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996, pp. 197 - 230 French, P A. Responsibility Matters. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1992 Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1990): Wahrheit und Methode - Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik. 6th edition Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Gehlen, A Der Mensch: seine Natur und seine Stellung in der Welt. 13th edition Wiesbaden: UTB, 1997 Habermas, J. Faktizität und Geltung: Beiträge zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des demokratischen Rechtsstaats. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1998 Habermas, J Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns, Frankfurt a. M., Suhrkamp, 1981 Heng, M. S. H. & de Moor, A. "From Habermas’s Communicative Theory to Practice on the Internet" in: Information Systems Journal (13), 2003, pp. 331 - 352 Herring, S "Posting in a Different Voice: Gender and Ethics in Computer-Mediated Communication, " In: Ess, C (ed.) Philosophical Perspectives on Computer-Mediated Communication. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996, pp. 115 - 145 Himanen, P. The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age. London: Secker & Warburg, 2001 Hirschheim, R. & Klein, H. K. "Crisis in the IS Field? A Critical Reflection on the State of the Discipline," Journal of the Association for Information Systems (4:5), 2003, pp. 237 - 293 Hirschheim, R. & Klein, H. K. "Realizing Emancipatory Principles in Information Systems Development: The Case for ETHICS," MIS Quarterly (18:1), 1994, pp. 83 - 109 Hirschheim, R. & Klein, H.K. "Four Paradigms of Information Systems Development," Communications of the ACM (32:10), 1989, pp. 1199 - 1216 Howcroft, D. & Wilson, M. "Paradoxes of participatory practices: the Janus role of the systems developer" in: Information and Organization (13:1), 2003, pp. 1 - 24 Huntington, S.P. The Clash of Civilisations? In: Foreign Affairs Summer 1993 Volume 72, Number 3, pp. 2 - 49 Johnson, D. G. "Ethics On-Line," in: Spinello, R A. & Tavani, H T. (eds.) Readings in Cyberethics. Sudbury, Massachusetts et al.: Jones and Bartlett, 2001, pp. 26 - 35 28 Klein, H. K. & Myers, M. D. "A Set of Principles for Conducting and Evaluating Interpretive Field Studies in Information Systems," MIS Quarterly (23:1), 1999, pp. 67 - 94 Kolb, D. "Discourse Across Links," Ess, Charles (ed.) Philosophical Perspectives on ComputerMediated Communication. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996, pp. 15 26 Kolko, B. E. "Intellectual Property in Synchronous and Collaborative Virtual Space," Baird, R. M., Ramsower, R. & Rosenbaum, S E. (eds.) Cyberethics - Social and Moral Issues in the Computer Age. New York: Prometheus Books, 2000, 257 - 281 Levinas, E, Le temps et l’autre. Paris: Quadrige / Presses Universitaires de France, 1983 Lyytinen, K & Hirschheim, R. (1988): "Information Systems as Rational Discourse: an Application of Habermas Theory of Communicative Action," Scandinavian Journal of Management (4:1/2), 1988, pp. 19 - 30 Metcalfe, M & Lynch, M, "Arguing for Information Systems Project Definition," in: Wynn, E; Whitley, E; Myers, M D. & DeGross, J (eds.) Global and Organizational Discourse About Information Technology: Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003, pp. 295 321 Myers, Michael, D & Avison, David (eds.) (2002): Qualitative Research in Information Systems: a Reader. London et al.: Sage O’Leary, S D. & Brasher, B. E. "The Unknown God of the Internet: Religious Communication from the Ancient Agora to the Virtual Forum," Ess, C. (ed.) Philosophical Perspectives on Computer-Mediated Communication. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996, pp.: 233 - 269 Raboy, M. (1997): "Cultural Sovereignty, Public Participation, and Democratization of the Public Sphere: The Canadian Debate on the New Information Infrastructure," Kahin, B & Wilson, E J. (eds.) National Information Infrastructure Initiatives Vision and Policy Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: MIT Press, 1997, pp. 190 216 Ricoeur, P. Soi-même comme un autre. Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1990 Riis, A M "The Information Welfare Society: An Assessment of Danish Governmental Initiatives Preparing for the Information Age," Kahin, B & Wilson, E J. (eds.) (1997): National Information Infrastructure Initiatives Vision and Policy Design. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: MIT Press, 1997, pp. 424 - 456 Robey, D. & Azevedo, A. "Cultural Analysis of the Organizational Consequences of Information Technology," Accounting, Management and Information Technologies (4) 1, 1994, pp. 23 - 37 29 Schultze, U & Leidner, D "Studying Knowledge Management in Information Systems Research: Discourses and Theoretical Assumptions," MIS Quarterly (26:3), 2002, pp. 213 - 242 Settle, Amber & Berthiaume, André (2002): Debating E-commerce: Engaging Students in Current Events. In: Journal of Information Systems Education 13(4): 279 - 285 Smith, M. "Tools for Navigating Large Social Cyberspaces," in Communications of the ACM (45:4), 2002, pp. 51 - 55 Steinmann, H. "Business Ethics in a Modern Society," Business Ethics in a Modern Society (Estonian Business School Review No 12). Talinn: EBS, 2001, pp. 11 - 18 Straub, D.W., Loch, K.D. & Hill. C.E. "Transfer of Information Technology to the Arab World: A Test of Cultural Influence Modelling," Journal of Global Information Management, 9, 2001, pp. 6 - 28. Ulrich, W, "A Philosophical Staircase for Information Systems Definition, Design, and Development", in: Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (3:3), 2001, pp. 55 - 84 van den Hoeven, J, "The Internet and Varieties of Moral Wrongdoing," Langford, D (ed.), Internet Ethics, London: McMillan, 2000, pp. 127 - 153 Walsham, G. "Cross-Cultural Software Production and Use: A Structurational Analysis," in: MIS Quarterly (26:4), 2002, pp. 359 - 380 Ward, J & Peppard, J "Reconciling the IT/business relationship: a troubled marriage in need of guidance," Journal of Strategic Information Systems 5, 1996, pp. 37 - 65 Weber, M "Objectivity and understanding in economics," Hausman, D M. (ed.) The Philosophy of Economics: An Anthology. 2nd edition Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 69 - 82 Weber, M The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. London, Free Press, 1947 Weckert, J "What is New or Unique about Internet Activities?" In: Langford, D (ed.): Internet Ethics. London: McMillan, 2000, pp. 47 - 63 Wynn, E H., Whitley, E. & Myers, M. "Placing Language in the Foreground: Themes and Methods in Information Technology Discourse," Wynn, E; Whitley, E; Myers, M D. & DeGross, J (eds.) Global and Organizational Discourse About Information Technology: Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003, pp. 1 - 12 30