The Impact of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) - Purdue e-Pubs

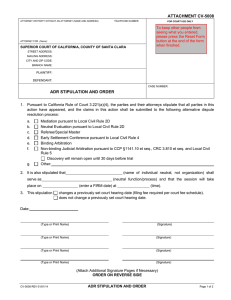

advertisement