A Longitudinal Assessment of Consumer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction

advertisement

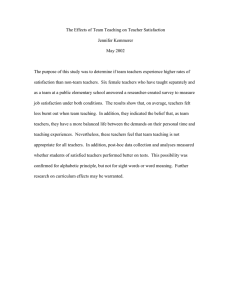

A Longitudinal Assessment of Consumer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction: The Dynamic Aspect of the Cognitive Process Author(s): Priscilla A. LaBarbera and David Mazursky Source: Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Nov., 1983), pp. 393-404 Published by: American Marketing Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3151443 . Accessed: 12/10/2013 07:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . American Marketing Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Marketing Research. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions I A. LaBARBERA and DAVIDMAZURSKY* PRISCILLA A simplifiedcognitivemodelis proposedto assess the dynamicaspect of consumer in consecutivepurchasebehavior. Satisfactionis found satisfaction/dissatisfaction to have a significantrole in mediatingintentionsand actual behaviorfor five product classes that were analyzed in the context of a three-stage longitudinalfield study. The asymmetriceffect found demonstratesthat repurchaseof a given brand is affected by lagged intentionwhereas switchingbehavioris more sensitiveto dissatisfactionwithbrandconsumption.An attemptto predictrepurchasebehavioron the basis of the investigatedcognitivevariablesyielded weak results. However,repurchase predictionswere improvedwhen the model was extended to a multipurchase setting in whichprior experiencewith the brandwas taken into account. A of Consumer Longitudinal Assessment The Satisfaction/Dissatisfacti Dynamic of the Aspect Cognitive Process III A simple model of satisfaction as a function of expectations and disconfirmation (i.e., the extent to which the expectationsare met) was suggested by Oliver (1980a) to summarize the early research on the antecedents of satisfaction (see Anderson 1973, Cardozo 1965, Oliver 1977, Olshavsky and Miller 1972, and Olson and Dover 1979 for representative reports). Oliver (1980b) also proposed a cognitive model to account for the consequences as well as the antecedents of satisfaction in the formation of purchase intentions. This model postulates that satisfaction acts as a mediator between preexposure and postexposure attitudes. In contrast to treating satisfaction as a static dependentvariable, the cognitive model recognizes that satisfaction is part of the dynamic purchase process and influences repurchase intentions. Longitudinal research is needed to test the feedback effects of postpurchase behavior hypothesized by an ex- tended cognitive model (Oliver 1980a). Although a few longitudinal studies of consumer behavior have been reported (see Oliver 1977, automobile purchases; Oliver 1980b, flu vaccination program; Swan 1977, department store shopping; Swan and Trawick 1981, restaurants), the analysis of the purchase process in the consumer satisfaction literature has not progressed much beyond the prepurchaseand postpurchase conditions pertaining to a single purchase activity. Only in other areas of research, such as job satisfaction, have multiple-exposure studies analyzed the relationship between satisfaction and two or more trials (see Ilgen 1971; Ilgen and Hamstra 1972; Weaver and Brickman 1974). The purpose of our article is to extend the understanding of consumer satisfaction by examining multiple consecutive product purchases in the context of a field study. Oliver (1980a) identified adaptation level theory (Helson 1964) as a promising theoretical framework to support several findings of consumer satisfaction studies. This theory seems to be appropriate for explaining how past cognitions, which serve as the adaptation levels, are mediated by present satisfaction in influencing repeat purchase behavior. The theory, which has its roots in physiology, stipulates that previous experience with the phenomenon under study generates an adaptation level or anchor for subsequent judgments. According to Helson (1964, p. 128), "Stimuli above [the] adaptation level *Priscilla A. LaBarberais Associate Professor of Marketing, Graduate School of Business Administration, New York University. David Mazursky is Lecturer, School of Business Administration, Hebrew University, Jerusalem. The authors acknowledge financial support of this research from the New York University Research Challenge Fund. Thanks are expressed to Jacob Jacoby, Srinivas Reddy, and Carol Surprenant for their valuable comments on drafts of this article. 393 Journal of Marketing Research Vol. XX (November 1983), 393-404 This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NOVEMBER 1983 JOURNALOF MARKETING RESEARCH, 394 give rise to positive gradients of excitation and responses of one kind, while stimuli below [the] adaptation level give rise to negative gradients of excitation and responses of an opposite kind." In our study, prior intentions were hypothesized to act as the adaptation level for future intentions (Oliver 1980b, p. 462) and the satisfaction/dissatisfaction from the brand consumption represented the stimulus that mediates the changes. Thibout and Kelley's (1959) comparison level theory provides another useful framework to explain the role of satisfaction in mediating preconsumption and postconsumption cognitions. The theory predicts that satisfaction develops from an interactionamong individuals, and results from the discrepancy between outcomes and a certain comparison level. LaTour and Peat (1979) applied the theory in the context of a product purchase setting. The theory is particularly appealing because it adds a dynamic aspect whereby outcomes from a present experience modify the comparison level for future consideration. According to comparison level theory, a high level of satisfaction results in a greater difference between outcome and the comparison level which yields a higher intention to repurchase the brand. A COGNITIVEMODEL OF REPEAT PURCHASE BEHAVIOR Several researchers have examined the dynamic aspect of the purchase-repurchaseprocess in which satisfaction is treated as the feedback of purchase behavior. In the revised Howard and Sheth model (Howard 1974) the consumptionof the branddeterminesthe satisfactionlevel which, in turn, affects the revised attitude as well as the intention to repurchase the brand. In Oliver's (1980b) cognitive model of the purchase process, the revised intention to repurchase the brand is formulated in a way similar to that suggested by Howard (1974): I, = f (l-1, SAT,ATT,). The intention (I,) in the present period is determined by three components, (1) the previous intention (I,-_), which serves as the adaptation level for the current intention, (2) the satisfaction level (SAT) from the brand consumption, which mediates the changes between the prepurchase and postpurchase intentions, and (3) the current attitudinal level (ATT,). In reviewing the consumer satisfaction literature, LaTour and Peat (1979, p. 434) conclude, "Given that attitude and satisfaction are both evaluative responses to products, it is not clear whether there are any substantive differences between the two." However, Oliver (1981) suggested a conceptual difference between attitude and satisfaction. He defined satisfaction as "an evaluation of the surprise inherent in a product acquisition and/or consumption experience." The surprise or excitement is of finite duration, so that satisfaction soon decays into attitude toward purchase. Because the purpose of our study was to extend the investigation to behavior in a multiple-purchase setting, with short time spans between purchases and cognitive evaluation, we used a measure of satisfaction/dissatisfaction to estimate postpurchase evaluation. In addition to the theoretical problem of differentiating between attitude and satisfaction for an extended experience (i.e., repurchase behavior), Oliver (1980b) confronted practical difficulties in testing his cognitive model due to multicollinearity among both preexposure and postexposure cognitions. Because of the theoretical and practical issues related to the distinction between satisfaction and attitude, a simplified model is suggested for the investigation of successive purchase-repurchaseevents. In this model the repurchaseis tested as a categorical variable (repeat purchasers versus brand switchers), satisfaction/dissatisfaction estimates postpurchase evaluations, and intention is believed to act as the adaptation variable. This model permits investigation of the adaptation level formation in which satisfaction mediates the adjustments. A high satisfaction level will have a positive impact on the intention level for repeat purchasers, whereas dissatisfaction could have a negative influence on the intention level for brand switchers. The cognitive process studied is postulated to proceed as follows. It- - Pt-, SAT-> It-- Pt+ This process yields the following general model. (1) P,t+ = f (I, SAT, P,, I,t-) Let RP denote the repeat brand purchase behavior and SW be the switching behavior. Because P,+l is a categorical variable denoting overt behavior (P,+i = RP for repeat purchasers and P,+l = SW for switchers) and is a function of 1, (Howard 1974), a simple path analytical model is suggested: (2a) I,= gl (I,_-,SAT) and (2b) SAT = g2 (I,-). The model should be analyzed separately for repurchasers and switchers because of possible asymmetry in the relationship between the cognitive variables and consumer decision implications. Several hypotheses about the average intensitiesof satisfactionand intentions across consumers for a given brandare postulated by the model: l,IRP> I,fSW, (3) (4) > SAT,ISW, SAT,IRP and (5) i,-,\RP > i,- ISW. That is, equations 3 and 4 stipulate that the average revised intention and satisfaction levels are higher for consumers who subsequently repeat the purchase of the same brand than for those who switch. Likewise, hy- This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION 395 pothesis 5 implies that the decision to repurchase is preceded by differences in the intention level during the lagged period. This hypothesis is attributed to the fact that a repeat purchase decision (or switch) is generated gradually, and therefore is reflected in higher (lower) expectation and attitudinal favorability which form intentions in the preceding period. The hypothesized rdle of satisfaction in mediating the intention level implies that within each group (P,+l = RP or P,+1 = SW) the postpurchase cognitions will score higher than prepurchase cognitions for repurchasers. In contrast, postpurchase cognitions will be lower than prepurchase cognitions for switchers. Thus, for the repurchasers I,IRP> (6) ,t- IRP and for the switchers (7) !,ISW < !,-,ISW. Finally, the satisfaction/dissatisfaction from brand consumption is hypothesized to amplify the differences in the intention levels between the groups over time. This relationship is summarized by (8) (IIRP)- (IISW)> (I,- IRP) - (I,- SW). Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized cognitive process for the repurchaserand switcher groups for two consecutive brand purchases. In addition to the bivariate differences, a simultaneous relationshipamong the three cognitive variables (It_l, SAT, It) is hypothesized to yield the sequence It-_ -> SAT -> It. Satisfaction is predicted to mediate the difference between the intention levels to produce a relationship that is stronger than the direct effect of the lagged intention on revised intention. Figure 1 A PATHMODELOF SATISFACTIONDECISIONSAND INTENTIONLEVELREVISIONSUNDERLYINGOVERTBEHAVIOR PERIOD t-l INTENTION AND SATISFACTION J 4% PERIOD 1 I PERIODt Ir- I z 0 H H :4 Ci2 Repurchase Brand X H z 0 H Ez zH Pe rX, En F4 to :r H H Switch to Brand Y H 0 H (a) (b) TIME denotes the direct of prior effect intention on the revised intention of prior denotes the indirect intention on the revised effect intention on revised intention as mediated with brand consumption). by satisfaction (i.e., This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions the effect 396 JOURNAL OF MARKETING NOVEMBER 1983 RESEARCH, STUDY OBJECTIVES To date consumer satisfaction research has concentrated on a single purchase period. We investigated the role of satisfaction in determining repurchase intentions and overt behavior within the context of a longitudinal study. The dual purpose of our study was to (1) investigate the direct and indirect effects of satisfaction/dissatisfaction on the formation of revised intentions and overt behavior and test a simplified cognitive model over two consecutive purchase periods for five different product classes and (2) test the extent to which reported satisfaction/dissatisfaction and the appropriate intention levels directly predict repeat purchase behavior in the context of multiple consecutive purchasesin a field study. METHOD To obtain a consumer panel, a sample of 500 individuals was selected at random from five randomly selected telephone directories of residential communities in Connecticut. The potential participants received information aboutthe intendedstudy, theirresponsibilitiesif they chose to and were qualified to participate, and the reward for their cooperation.1 One hundred and eighty consumers who indicated a willingness to participate were asked to complete several items to determine how often they purchased each of 24 grocery products and to pretest the questionnaire designed for the study. One hundred and twenty-five consumers who purchased and used at least 12 of the 24 products on a biweekly basis were invited to join the panel.2 The research instrument was revised on the basis of the pretest findings. The final questionnaire consisted of three items pertainingto each of 24 grocery productssuch as tissues, coffee, and dish detergent. Respondents were asked to report the name of the brand currently in use, satisfaction with the current brand, and intention to repeat the purchase of the current brand. In addition, respondentswere asked whether they had purchasedor used another brand between the current and last questionnaires. Panel members completed questionnaires biweekly over a five-month period. Although 125 consumers responded to the first questionnaire, 38 panel members dropped out during various stages. The final analysis includes 87 consumers who completed each of the 10 questionnaires. This group represents 70% of the 125 consumers who were eligible to participateand 48% of the 180 consumers who indicated their willingness to participate. After collection of the data, the product classes were screened to identify those that most closely approximated a two-week interpurchase interval. Consumer recall of repurchase frequency served as the basis for the screening. The purpose was to eliminate bias in the ag'The reward was five books of S & H Green Stamps. 2Consumerswho did not qualify for panel participation received one book of S & H stamps. gregate analysis in which the disconfirmation period is assumed to be equal for all consumers. The five product classes that qualified for the analysis were margarine, coffee, toilet tissue, paper towels, and macaroni. Purchasebehavior was tracked indirectly by pretesting interpurchasefrequency and by inserting an additional question about purchases of other brands between periods. This indirect method was used to simplify the respondents' task, which would otherwise have entailed the completion of a purchase diary in addition to the 10 questionnaires.Though pretest results indicated that most consumers purchased a single item of a certain brand from a specific product category every two weeks (for the five product classes investigated), three exceptions to this pattern might have occurred during the study period. First, an "inventory" of a brand purchased previously could have been in use rather than the purchased brand. Second, two or more purchases could have been made during the two-week period. Third, two or more brands could have been purchased or used concurrently during the period. On the basis of the pretest findings we assumed that such patterns would not seriously affect the results. In addition, in several instances, consumers indicated that other brands were purchased or used between periods. Consecutive purchases that were interrupted by the purchase or consumption of other brands were deleted from the analyzed data files. Added to the last questionnaire was a section pertaining to respondent demographic characteristics. In many consumer behavior studies a comparison between respondents and nonrespondents indicates whether a response bias is present, but this procedure was determined not to be appropriate in our study because past researchdemonstratesthat purchase satisfaction does not correlate significantly with demographic variables (Westbrook and Newman 1978). Measures In measuring satisfaction/dissatisfaction, several researchers prefer an overall summary measure whereas others argue that satisfaction should be measured by a combination of attributes. Day (1977a) claims that there is no difficulty with measuring overall consumer satisfaction. Czepiel and Rosenberg (1976) justify the use of a single-item overall measure because it represents a summaryof subjective responses to several different facets. Other researchers use summative scales to measure satisfaction/dissatisfaction (Oliver 1980b; Swan and Trawick 1981; Westbrook and Oliver 1980). The pretest demonstrated that multiple-item measures designed to obtain informationabout many productclasses substantiallylimited the number of consumers willing to participate. A poor response due to questionnaire length could have caused a significant nonresponse bias. Moreover, because the questionnaire did not investigate many different issues, the use of several items to measure certain variables (i.e., satisfaction, intention)repeatedly over time might have resulted in artificial answers by re- This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 397 CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION spondents. Therefore, the use of summative scales in our research would probably have decreased rather than increased reliability. As suggested by psychometricians (Deutcher 1966; Hirsci and Selvin 1967; Kimberly 1976), a modification of the scales in a longitudinal study is appropriate;in our study this entailed the use of overall satisfaction and intention measures. Accordingly, the intention scale used ranged from "extremelylikely" to "not at all likely" and the satisfaction scale ranged from "completely satisfied" to "not at all satisfied." Both variables were measured on 5-point scales. ANALYSIS To investigate repurchase behavior, lagged variables for brand consumption within each product class were computed (Hull and Nie 1979). After deletion of missing values for consumers who did not purchase any brand within the product class during any of the 10 periods, and deletion of consecutive purchases which were interrupted by the purchase of another brand between periods, 2568 cases of two consecutive purchases of the same brand within the product category were detected and consisted of 1969 repeat purchasesand 599 switches. A computed categorical variable called CH, to denote change for repurchase (CH = 0) versus switching behavior (CH = 1), was matched with the intention and satisfaction level of the appropriateperiods. Each of the two consecutive purchase periods constituted the unit of analysis (because each consumer had more than one such "unit"). The Role of Satisfaction as a Mediating Factor To test the role of satisfaction in mediating intention, the analysis was performed separately for repeat purchasers and switchers who demonstrated the opposite overt behavior in the next successive period. A just identified general path analytical model (Duncan 1966) was applied to the two groups. The analysis first concentratedon the total population. For purposes of testing the generalizability of the findings, the total population was subsequently split into the five product categories in an individual analysis. The variables were standardized to represent the standardized regression path coefficients. Path analysis observations were analyzed for three points in time. For the first observation, the intention to purchase the previously consumed brand was measured (I,_in Figure 1). In the next time period the brand purchase observation (Pt) was considered as well as the satisfaction (SAT) from the brand consumption and the intention (It) to repurchase the same brand. For the third observation, the actual repurchase (or switching) observation (P,t+) was obtained. In this process, which was applied on the aggregate level for three successive periods, the individual cases were used as input. Correlational analysis revealed similar patterns of relationships investigated for repeat purchasers and brand switchers among the three variables (I,_,, SAT, I,). For the total population, the strongest relationship is between the two postpurchase variables (r = .73 for repeat purchasers and r = .77 for switchers). Simple correlations exceed the r = .34 level. The mean values of lagged intention, satisfaction from the previous purchase stage, and revised intentionare higher for repeat purchasersthan for brand switchers (as postulated in equations 2, 3, and 4). Table 1 demonstrates that the differences are significant across four of five product classes. Two alternative explanations may account for this difference. First, the intuitive explanation is that, in comparison with brand switchers, consumers intending to repurchase the same brand score higher on the revised intention as well as the satisfaction from the previous consumption. Even the previous intention shows significant differences between the two groups. Alternatively, the previous purchase may not necessarily be the first trial of the brand and, by taking consumption experience into account, a longer history might yield a higher level of previous intention. Different purchase histories of the same brand between the two groups could affect the initial investigated intention level. In a subsequent section we demonstratethat such an effect accounted for part of this difference. Our study concentrated on the deviations of the revised cognitions from the lagged intention (within each of the two groups) with the lagged intention serving as a reference point for the satisfaction mediation. Thus, it emphasized the relative changes of the revised intention from the original level. However, the absolute value of the previous intention (which is different for the two Table 1 IN MEAN SCORES OF LAGGEDINTENTION,SATISFACTION,AND INTENTIONTO REPURCHASEBETWEEN DIFFERENCES AND SWITCHING GROUPS THEREPURCHASE ,-i SAT I, Aggregate Repur- Switchchase ing 4.41 4.07 4.48 4.07 4.46 3.91 Diff. 0.34a 4.41a 0.55a Margarine Repur- Switchchase ing Diff. 4.23 0.11 4.34 4.48 4.12 0.36a 3.93 0.49a 4.42 Coffee Repur- Switchchase ing 4.24 4.44 4.16 4.55 4.03 4.51 Toilet tissues Diff. 0.20b 0.39a 0.48a Repur- Switchchase ing Diff. 4.41 3.95 0.46a 4.44 3.97 0.47a 4.45 3.81 0.64a Paper towels Repur- Switchchase ing Diff. 3.75 0.62a 4.17 4.42 3.91 0.51a 3.65 0.77a 4.42 'p < 0.01. bp < 0.05. This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Macaroni Repur- Switchchase Diff. ing 4.16 0.32a 4.48 4.53 4.20 0.32a 4.14 4.49 0.35a JOURNAL OF MARKETING NOVEMBER 1983 RESEARCH, 398 groups; see Figure 1) might account for some of the differential changes in the revised intention as affected by the satisfaction intervention. To control for both the absolute level and the relative intention adjustments, a ttest3 was performed on the difference over time in intention levels between the two groups (see equation 8). The test shows that for the two groups the difference in the intention levels increases significantly (p < .01) between the two periods. Table 2 shows the results of the paired t-test for the differencebetween the means of the intentionlevels within the two groups (see equations 6 and 7). The differences between the previous intentions and the revised adaptation levels support the expected direction in all cases although not all are statistically significant. Table 3 summarizes the path analysis findings for the effects of prepurchase intention and postpurchase satisfaction on the revised intention to repurchase the brand. In both groups (and across all product classes) the effect of the lagged intention through the intervention of satisfaction is larger than the direct effect of the initial adaptation level on revised intentions. Likewise, the residual path coefficients of the model, in predictingthe change in the revised intention, indicate that a relatively large part of the variance is explained by both the prepurchase and postpurchase predictors (E3 in Table 3). Potential multicollinearity among the independent variables (I,-,, SAT) might influence those effects in an arbitrarydirection. The average correlation among the two independent variables is r = 0.37. However, in 10 of the 12 simple correlation matrices the correlations among the independent variables are the lowest. This finding might indicate that the chance occurrence of multicollinearity was minimized. A systematicdifference between the two groups is found in the path analysis presented in Table 3. The direct effect of the previous intentionon the revised level is higher and more significant for the repeat purchasers than for brand switchers. The opposite dominance appears in the case of brand switchers, for whom the effect of dissatisfaction on the revised intention yields larger path coefficients in all cases, with the exception of one product class. Such an observation was expected because the variability in satisfaction/dissatisfaction scores is larger 3Equation 8 was computed as follows: AI,_, = I,_- I RP - I,_, I SW = 0.338 AI, = I, I RP - I, I SW = 0.541 A(AX) = A(I,) - A(l,_,) = 0.204 Let S denote the pooled standard error; then S rnl,, s12+ n2s22 n, + n2 = 0.03, n \ i = + L n n 2 nl + n2 - 2 ni ?n2 J t = 6.8. Table 2 PURCHASE INTENTIONS RELATED MEANSOF PREVIOUS TO REPURCHASE VS. SWITCHING TO MEANINTENTION BEHAVIOR It-I Repeat purchase group Aggregate Margarine Coffee Toilet tissue Paper towels Macaroni Switching group Aggregate Margarine Coffee Toilet tissue Paper towels Macaroni -> , I,-1 Expected change Actual (n =) 4.41 4.34 4.43 4.41 4.37 4.48 + + + + + + +c + + + + + 1969 326 385 428 416 414 - _b c - - 599 121 130 116 118 114 4.07 4.23 4.23 3.97 3.75 4.15 aThesignificance of differences was computed by a correlated (pairs) t-test. The minus (-) sign denotes decrease whereas plus (+) denotes increase between the two variables. p < 0.01. cp < 0.05. for switchers than for repeat purchasers. To investigate the direct and indirect effects of lagged intentions on intention formation, consumers' evaluations of the cognitive variables were subsequently crossclassified. Whereas the path analysis focused on the changes in mean intensities of the appropriate cognitions, a three-way frequency analysis was conducted to examine changes in the frequencies of consumers represented in each of the cells. The three lowest values of both the intention and satisfaction scales were grouped to obtain these matrices. The first reason for this grouping was the upward skewness in the scales' frequency (which is a typical phenomenon in most satisfaction research). The second reason was to reduce the matrix of scales to low, medium, and high satisfaction and intention. Table 4 summarizes the results of this analysis. Entries of equality of SAT and I, intensities represent adjustment of the revised intention to the satisfaction/dissatisfaction level as denoted by footnote b. These figures may indicate the mediating effects of satisfaction/dissatisfaction on revised intention. In addition, equal intensities of lagged intention (I,1-) and revised intention (I,), denoted by footnote c, represent those respondents whose intention level was not affected by satisfaction/ dissatisfaction levels. The cells denoted by both footnotes b and c comprise all cases in which intensities of cognitions do not vary throughoutthe cognitive process. If the entries denoted by footnote c are larger than the other entries, we might expect that lagged intentions and satisfaction levels do, in fact, influence the level of the This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION 399 Table 3 DIRECT ARECT AND INDIRECT EFFECTS OF LAGGEDINTENTION TO (-) AND SATISFACTION (SAT)ON INTENTION REPURCHASE (4) Direct effecta SW Variable Product class 1,-, Aggregate 0.19b 0. 10b Margarine Coffee 0.27b 0.14b 0.07 0.01 Toilet tissues Paper towels Macaroni Aggregate Margarine Coffee 0.16b 0.16b 0.20b 0.65" 0.56" 0.79b 0.07 0.10 Toilet tissues 0.62b Paper towels Macaroni Aggregate Margarine Coffee Toilet tissues Paper towels Macaroni 0.65b 0.68b SAT RP Indirect Effect' RP Total Effecta SW RP SW 0.27b 0.25b 0.46b 0.35b 0.16b 0.14c 0.37b 0.24b 0.43b 0.46b 0.21c 0.38b 0.39b 0.47b 0.53b 0.65b 0.56b 0.79b 0.31" 0.31b 0.53b 0.74b 0.73b 0.83b 0.79" 0.62b 0.79b 0.71b 0.58 0.65b 0.68" 0.7 lb 0.68b 0.33b 0.74b 0.73 0.83b 0.32b 0.23b 0.31b 0.33b - - 0.21 0.20b - - Coefficients' residual path RP SW E2 = E2 = E2 = E2 = E2 = E2 = E2 = 0.94 E3 = 0.62 E3 = 0.66 E3 = 0.73 Ez = 0.98 E3 = 0.67 E2 = 0.89 E3 = 0.55 E3 = 0.51 E2 = 0.95 E3 = 0.57 E3 = 0.72 E2 = 0.95 E3 = 0.66 E3 = 0.66 E2 = 0.94 E3 = 0.64 E3 = 0.60 aStandardizedregression coefficients (P,) were obtained by applying a regression analysis on equations 2a and 2b. Let us denote I,_- by g, I, by r, and SAT by s. Accordingly, the indirect effect of g on r is equal to P ,s x P,sr and the direct effect of g on r is equal to Pg,r where Pi are obtained from equation 2a. The direct effect of s on r is equal to Ps,r obtained from equation 2b. bp 0.01. 'p c 0.05. revised intention. The results of Table 4 support the contention that lagged intention and the mediating effect of satisfaction contribute to the formation of intention levels. The magnitudes of the frequencies in each of the three investigated classes-the cells denoted by footnote b, the cells denoted by footnote c, and the rest of the entriesin the matrices-reveal a clear pattern.Both lagged intentions and satisfaction show high frequencies for all the values that coincide with similar values of revised intention. Moreover, between the two cognitions that are 0.91 0.96 0.91 0.93 0.88 0.87 postulated to affect the revised intention, the mediating effect of satisfaction appears to be more substantial than the lagged intention. The total population subsequently was split into repurchaserand switcher categories. One observation from the tables is noteworthy. Although an upward skewness in the satisfaction and intention scales is expected for repeat purchasers, a substantial skewness is also observed for switchers. For example, 261 respondents (43.5% of the switcher group) reported high satisfaction Table 4 A CROSS-CLASSIFICATION OF THECOGNITIVE VARIABLES I, Medium Low RP I,-1 SAT Count Low SW % Count Low 118 60 79 Med. 23 59 16 70 19 8 High Med. Low 39 61 25 Med. 20 71 8 9 4 69 High Low 38 45 46 High Med 22 51 21 14 6 70 High values are at c 0.01. X\2 significant p bEqualSAT -+ I, intensities. RP High SW RP SW % Total Count % Count % Totala Count % Count 40 41 30 39 29 31 55 49 30 197bc 10 59 20 14 151 10 5 84 19 62 72 67 70 74 62 71 82 73 6 23 10 6 54 6 2 18 7 38 28 33 30 26 38 29 18 27 16 82b 30 20C 12 9 77 5 13 100 20 61 1001 80 75 72 100 81 79 83 74 86 3 3 30 0 3 27 4 21 163 39c 27c 64b 28 13 84b 43 20 205bc 16c 7 102b 26 CEqual I,- -> I, intensities. This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions % 20 25 18 0 19 21 17 26 14 Total 15 12 107b 5 16 127b 24c 82c 1164b.c 400 JOURNALOF MARKETING NOVEMBER RESEARCH, 1983 with the brand although they switched brands in the subsequent period. The Effects of Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction on Future Behavior Consumersatisfaction/dissatisfactionresearchmay have substantial marketing implications if postpurchase evaluations largely predict future purchase behavior. The assumption that satisfaction/dissatisfaction meaningfully influences repurchase behavior underlies most of the research in this area of inquiry. However, the extent to which satisfaction/dissatisfaction influences future purchase behavior has not been investigated rigorously. One possible explanation for the lack of research on the linkage between satisfaction and repeat purchase may be a past concentration on the antecedents of satisfaction and research utilizing social psychological experimentation, which inhibited such investigations (Russo 1979). The purposeof this section is to investigatethe degree to which satisfaction/dissatisfaction and intentions (lagged and revised) predict future purchases. Equation 1 is a model demonstrating these relations. In contrast to the dearth of empirical research on the satisfaction/repeat purchase behavior link, the relationship between intention and repurchase behavior is well established (see Warshaw 1980 for a detailed review). For the most part these relationships have been found to be poor, particularlyin product-relatedsettings. For example, Bonfield (1974) calculated a correlation of 0.44 between intentions and fruit drink choices and Harrell and Bennett (1974) obtained r = 0.37 when intentions and physician prescribingbehavior were correlated. Thus, in our study a weak relationship between intentions and repurchase behavior was expected. Moreover, because satisfaction was posited in our proposed cognitive process to precede intentions in the sequence of causality, satisfaction/dissatisfaction was expected to yield correlations with purchase that are weaker than the intention/ future behavior relationship. A multiple discriminant analysis was used in which repeat purchase behavior (P,+l) was treated as the dependent variable. The dependent variable comprised repurchasers (RP) and switchers (SW). The independent variables were the lagged intention, satisfaction, and revised intention. Similar to the path analysis procedure, the analysis first was performed for the total population and subsequently employed for each of the five product classes. The results of the discriminant analysis are summarized in Table 5. Column 7 of this table shows the simple correlationsof the various cognitive variables and repeat purchase behavior. These correlations reveal that in all Table 5 THE EFFECTSOF LAGGEDINTENTION(It-,), SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION (SAT), AND REVISEDINTENTION(I,) ON BRANDREPURCHASE BEHAVIOR BETWEEN AND SWITCHING REPURCHASING BEHAVIOR (P,+1):A COMPARISON (5) 11 1 (3) Standardized function coefficients 0.758 0.176 0.199 Margarine I, SAT I,_ 0.728 0.421 -0.175 0.953 0.961 0.998 21.8 18.2 0.96 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 N.S. Coffee I, SAT It-1 0.864 0.177 -0.043 0.953 0.962 0.991 25.13 20.01 4.26 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.05 Toilet tissues I, SAT 0.717 0.153 0.319 0.932 0.952 0.968 39.76 27.31 18.06 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 Paper towels I, SAT ItI1 0.874 -0.164 0.414 0.906 0.951 0.942 54.79 27.26 32.53 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 Macaroni I, SAT 0.251 0.500 0.430 0.967 0.966 0.972 17.45 18.36 14.69 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 (1) Product Aggregate (2) Variable I, SAT Univariate F-ratios (4) Wilks' lambda Level 0.943 0.959 0.979 153.6 108.5 55.9 Significance P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 (6) Percent of cases correctly classified (7) Correlations with P,+1 0.24a 0.20a 0.15a 64.5 0.22a 0.20a 0.04 63.8 0.22a 0.19 0.09" 63.5 0.26a 0.22a 0.18a 68.8 0.30a 0.22a 0.24a 67.4 I,-_ 0.18a 0. 18a 0.16a 64.4 aSignificant at p < 0.01 level. bSignificant at p < 0.05 level. This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION cases satisfaction/dissatisfaction is significantly correlated with repeat purchase behavior (p < 0.01). Although these correlations are generally poor in magnitude they are stable across all the studied product classes (r is between 0.18 and 0.22). In addition, the simultaneous analysis of all three variables (column 3) shows that the relative contribution of satisfaction/dissatisfaction to the function is low in comparison with that of the revised intention level. This pattern is consistent across all product classes except macaroni, for which the relative importance of satisfaction is the highest among the three cognitions. Although significant differences appear for most comparisons between the groups (column 5), indicating that switchers and repurchasers differ in their cognitive process, the overall strength of the three investigated cognitions in predicting future purchase behavior appears to be low. This conclusion is based on the high scores of Wilks' lambda(column 4) and the low percentageof cases correctly classified (column 6). Extention to a Multiple Repurchase Framework We have focused on a model of purchase-repurchase behavior pertaining to two consecutive periods. An interesting issue is the change in satisfaction levels as a function of consumers' experience with the consumed brand. In this section we extend the model to encompass additional consecutive purchase periods. The question addressed is: "To what extent are brand loyal consumers likely to switch brands?" That is, by knowing that the repurchaser group comprises consumers who repurchased the same brand several times successively, can we improve the predictions about repurchase behavior provided by the three-stage model? Equation 9 specifies the extended model in which PE (denoting prior experience) is believed to affect the intensities of the investigated cognitions, namely, lagged intentions, satisfaction, and revised intention to repurchase. The general extended model is (9) P,+ = f(It, SAT,,It-i, PE). More specifically, in the extended model we add two consecutive periods4 to examine an experience record of at least three repeat purchase occurrences. Equation 10 is the model tested. (10) Pt+l = f(I, SAT, P,, Itl, P,_-, P,-2). Consumer cognitions, mediated by additional experience derived from consecutive repurchasebehavior, were expected to result in greater discriminating power between repurchase and switching in comparison with the first analysis. In addition, because the repurchasergroup 4The decision to add two periods is a compromise between including more previous purchase experience and a sufficient representation of respondents in the multivariate analysis. 401 (in the previous discriminant analysis) was replaced by brand loyal consumers, the relative importance of satisfaction in predicting repurchase behavior was expected to decrease and the opposite observation was expected for intention levels. The assumption that adaptation levels stabilize over time underlies this proposition. A computed variable called LOY to denote the number of successive repurchases of the same brand was computed on the basis of the lagged values of the previously defined CH variable (i.e., switching versus repurchase behavior). Consumers who repurchased the same brand at least two consecutive times constituted the first discriminantgroup whereas consumers' overt switching behavior was the criterion for generating the second group. Table 6 summarizes the results of a discriminant analysis conducted to test the effects of experience and loyalty on consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction and overt repurchasebehavior. A comparison of this analysis (Table 6) with the first discriminant analysis (Table 5) reveals certain patterns. First, predictions of repurchase behavior are improved when experience with consecutive purchase of the same brand is taken into consideration. This finding is derived by comparing columns 4 and 6 of both tables. Both the decrease in Wilks' lamba and the increase in the correctly classified cases demonstrate that such a pattern is consistent across the studied products. The findings indicate that the low probability of brand loyal consumers switching brands is influencedby higher satisfactionand, consequently, higher intentions to repurchasethe brand. However, despite this improvement the overall predictions of these cognitions in repurchase decisions are relatively weak. A second pattern is indicated by changes in the relative importance of the three investigated cognitions. On the aggregate level, the relative contribution of satisfaction and revised intention to the overall function decreases (as shown in column 2 in both tables) and the relative contribution of lagged intentions increases for brand loyal behavior. Whereas the relative importance of revised intentions to repurchase is the highest, as posited in the assumption that revised intention is the last cognitive stage prior to purchase decisions, it is not enhanced when brand loyal behavior is investigated. However, a comparison of lagged intention contributions between the two analyses reveals that this cognition's relative importance is increasing across four of the five investigated product classes. This finding reinforces the conclusion that intentions to repurchase increase and then gradually stabilize as consumers repeat their purchase of the same brand. DISCUSSION Our findings strongly support the role of satisfaction in mediating revised intentions and overt behavior. Our study differs from much of the past research in that it is modified for repetitive brand purchases. However, the patterns found support previous theoretical approaches This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 402 JOURNAL OF MARKETING NOVEMBER 1983 RESEARCH, Table 6 THEEFFECTS WITHBRANDON BRANDREPURCHASE OF EXPERIENCE BEHAVIOR THROUGH COGNITIONFORMATION: A COMPARISON BETWEEN BRANDLOYAL AND SWITCHING BEHAVIOR Aggregate 1, SAT ,I-i (3) Standardized function coefficients 0.727 0.096 0.336 Margarine /, SAT ,_-i 0.638 0.351 0.194 0.892 0.909 0.970 35.1 29.2 9.0 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.01 Coffee /, SAT 1,_, 0.611 0.230 0.306 0.896 0.908 0.937 38.4 33.4 22.2 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 Toilet tissues 1, SAT 1,,- 0.784 -0.065 0.444 0.870 0.919 0.912 55.6 32.6 35.9 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 Paper towels /, SAT 1/,1 0.801 -0.109 0.444 0.802 0.898 0.860 89.7 41.3 59.0 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 Macaroni /, SAT 1,-1 0.422 0.477 0.232 0.923 0.925 0.950 30.2 29.4 19.3 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 P < 0.001 (1) Product (2) (1) Variable (5) (4) Wilks' lambda 0.889 0.915 0.929 Uvate Univariate F-ratio F-cases Level Significance 238.7 P < 0.001 160.3 P < 0.001 131.1 P < 0.001 (6) Percent of correctly classified (7) Correlation with P,+1 0.35' 0.29a 0.26' 69.2 0.35' 0.30a 0.26a 67.0 0.32a 0.30a 0.25a 65.6 0.36a 0.28a 0.30" 71.9 0.44a 0.32a 0.37" 73.1 0.28' 0.27a 0.22' 66.0 'Significant at p < 0.01 level. addressing the cognitive process underlying purchase behavior. Our study, which examines the cognitive process for more than a single purchase activity, supports an extension of the role of satisfaction in purchase behavior from a static to a longitudinal perspective. The upward and downward shifts of satisfaction, which result in changes of the adaptation level in parallel directions and the dominance of the I,-i -- SAT-> I, relationship, demonstrate the importance of satisfaction/dissatisfaction in explaining the behavior of repeat purchasers and brand switchers. Although the changes in the adaptation level confirm the expected shifts, those changes in most cases are not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with Oliver's (1980b) observation that "the adaptation level effect is remarkably resistant to extinction." The statement can be generalized to the three-stage analysis. Although satisfaction affects the intention level, the shifts in the adaptationlevel for each group are not substantial. It is important to note, however, that the difference between the two groups' intention levels increased significantly between the two periods. This finding indicates that overall satisfaction has a meaningful role in determining the revised intention to repurchase. As one might expect, the mean revised intentions are significantly different for consumers who eventually repeated the purchase of the same brand and those who switched. Likewise, the satisfaction level is a significant explanation of intention formation. The mean lagged intention to purchase the brand in the previous period is also different for the two groups. This finding supports the proposition that the underlying beliefs which give rise to the formation of postpurchase cognitions are internalized to the extent that attitude, or perhaps intention, persists over a long period of time (Oliver 1980b). Although lower in magnitude than the difference in the revised intention, a significant difference in lagged intentions is found in four of five product classes between consumers who made a decision to repurchase and those who switched in the following period. This finding indicates that the repeat purchase group comprises mainly brandloyal consumers. It is congruentwith Day's (1969) statement that there is a difference between intentional loyalty and spurious loyalty associated with consistent repurchaseof one brand. When the population was split on the basis of whether or not the brand was repurchased, an asymmetrical relationship among the three variables was revealed for the two groups. The direct relationships between the preand postpurchase intention levels are stronger for brand loyal consumers than for brand switchers. This observation was expected because the beliefs about the brand are more stable and internalized for brand loyal consumers. However, the findings suggest that switcher be- This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 403 CONSUMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION liefs are more sensitive to the dissatisfaction from consuming the brand. Despite the empirical support for the cognitive process underlying repurchasebehavior, the strength of the studied cognitions in directly predicting repurchase or switching behavior is not substantial. Only when consumers' prior experience with the brand was incorporated into the model were predictions somewhat improved. This finding suggests that other situationalfactors, such as coupons and sales, may influence purchase decisions despite a high satisfaction with the currently consumed brand. Satisfaction and intention are found to increase as the loyalty to the brand increases (when brand loyalty is measuredin a numberof successive purchasesof the same brand). However, the relative importance of satisfaction in predicting repurchase appears to decrease as loyalty increases. Thus, it is likely that a certain threshold of satisfaction must be met to lead to a repeat purchase of the brand. Moreover, the longer the sequence of repeat purchases, the more the experience with the brand accounts for repurchase behavior. One managerial implication may be that marketing efforts appealing to consumer satisfaction with the brand should be expended in the early stages of consumer brand experience. In later stages of consumers' experience with the brand a reasonable level of satisfaction should be maintained,so that long-run intention levels do not decrease. A second managerial implication is that reports indicating consumers are "extremelysatisfied" with the brand followed by indications of high intention to repurchase do not necessarily indicate that switching behavior will be insignificant. Although the cognitive process is important in predicting repurchase behavior, situational factors must be incorporated into future models to improve predictions; Finally, an implication for marketing research is that because adaptation levels tend to stabilize as brand loyalty increases, both satisfaction and intention should be measured for those segments (or products) primarily characterized by low brand loyalty. For segments (or products) characterized primarily by brand loyal consumers, intention levels may be sufficient to represent the cognitive influence on repurchase behavior. LIMITATIONSAND FUTURE DIRECTIONS Our study tested an abbreviated cognitive model. The goal was to test in a field study situation the dynamic aspect of the role of satisfaction in revising repurchase intentions for several consecutive purchase activities. A limitation of the study is that it did not simultaneously test all the variables involved in the dynamic cognitive model proposed by Oliver (1980b) because of theoretical and practical issues. The study was based on panel data. Most consumer satisfaction studies are conducted in experimental settings or are field studies investigating a single purchase event. Although a panel study using reported purchase data might be considered more reliable, it could be biased if panel members report a higher satisfaction or intention level to justify their repeat purchases. However, because the study data were not based on recall of previous periods and the time interval between questionnaires was two weeks, we believe such potential bias was minimized. In addition, frequently purchased goods were the focus of study. Although a relatively large sample of frequently purchased products was included, further research is needed to examine other products, such as high involvementgoods. In relationto low involvement goods, Day (1977b) argued that the consumer may not make any evaluation for many simple products. Swan and Trawick (1979) found support for the contention that the extent of product evaluation may depend on the product class, each product class representing a different level of involvement. Despite this criticism, we believe that measuring satisfaction may be appropriate in the context of longitudinal studies even for low involvement products. The first reason for this contention relates to the timing of measurement. Many of the past investigations reported in the consumer satisfaction literature are based on definitions that do not consider the importance of measurement timing. Only recently has Oliver (1981) suggested a definition of satisfaction which stipulates that satisfaction rapidly decays into attitude. According to this view, a measure of immediate past usage satisfaction would yield the highest construct validity of satisfaction measurement. Because of the frequency of reporting used in our study, the measurement timing limitation was probably minimized. The second reason for believing that measuring satisfaction may be appropriatefor low involvement goods relates to the importance of satisfaction in repurchase decisions. Although some consumers may not make any evaluation when satisfaction is measured as a dependent variable, we believe they do think of past satisfaction prior to a repurchase decision. Thus, though consumers might often respond, "I don't think about it," when they do not have to confront a repurchase decision, the question, "How satisfied are you?" may be appropriate in a repurchase decision situation. The order of successive purchases of a brand within the product class was used as the measure of brand loyalty in our study. In reality, however, consumers might be loyal to several brands concurrently. Different measures of brandloyalty might lead to results different from ours. Finally, a broadening of the consumer satisfaction literatureto longitudinal designs should be continued. An extension of the design to encompass a longer sequence of successive purchase behavior would permit further brand experience to be taken into account. In addition, including situational factors, such as company reputation and sales, would probably improve predictions of brand repurchase behavior. This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 404 JOURNALOF MARKETINGRESEARCH,NOVEMBER1983 REFERENCES Anderson, R. (1973), "Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance," Journal of Marketing Research, 10 (February), 3844. Bonfield, E. (1974), "Attitude, Social Influence, Personal Norms, and Intention Interaction as Related to Brand Purchase Behavior," Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (November), 379-89. Cardozo, R. (1965), "An Experimental Study of Consumer Effort, Expectations and Satisfaction," Journal of Marketing Research, 2 (August), 244-9. Czepiel, J. A. and L. T. Rosenberg (1976), "Consumer Satisfaction: Toward an Integrative Framework," Proceedings of the Southern Marketing Association, 169-71. Day, G. S. (1969), "A Two-Dimensional Concept of Brand Loyalty," Journal of Advertising Research, 9 (Number 3), 29-35. Day, R. L. (1977a), "Alternative Definitions and Designs for Measuring Consumer Satisfaction," in The Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction, H. K. Hunt, ed. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. (1977b), "Toward a Process Model of Consumer Satisfaction," in The Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction, H. K. Hunt, ed. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute, Report No. 77-103, 153-83. Deutcher, I. (1966), "Words and Deeds: Social Science and Social Policy," Social Problems, 13, 237-47. Duncan, O. D. (1966), "Path Analysis: Sociological Examples," American Journal of Sociology, 72, 1-16. Harrell, G. and P. Bennett (1974), "An Evaluation of the Expectancy/Value Model of Attitude Measurement for Physician Prescribing Behavior," Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (August), 269-78. Helson, H. (1964), Adaptation Level Theory: An Experimental and Systematic Approach to Behavior. New York: Harper and Row. Hirsci, T. and H. C. Selvin (1967), Delinquency Research: An Appraisal of Analytical Methods. New York: Free Press. Howard, J. A. (1974), "The Structure of Buyer Behavior," in Consumer Behavior: Theory and Application, John V. Farley, John A. Howard, and L. Winston Ring, eds. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 9-32. Hull, H. and Nie, N. H. (1979), SPSS Update. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 111-14. Ilgen, D. R. (1971), "Satisfaction with Performance as a Function of the Initial Level of Expected Performance and the Deviation from Expectations," Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 345-61. and B. W. Hamstra (1972), "PerformanceSatisfaction as a Function of the Difference Between Expected and Reported Performance at Five Levels of Reported Performance," Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 7, 359-70. Kimberly, J. R. (1976), "Issues in the Design of Longitudinal Organizational Research," Sociological Methods and Research, 4, 321-47. LaTour, S. and N. Peat, (1979), "Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Satisfaction Research," in Advances in ConsumerResearch, Vol. 6, W. L. Wilkie, ed. Miami: Association for Consumer Research. 431-37. Oliver, R. C. (1977), "Effect of Expectation and Disconfirmation on Postexposure Product Evaluations: An Alternative Interpretation,"Journal of Applied Psychology, 62 (August), 480-6. (1980a), "Conceptualization and Measurement of Disconfirmation Perceptions in the Prediction of Consumer Satisfaction," in Proceedings of Fourth Annual Conference on Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, H. K. Hunt and R. L. Day, eds. Bloomington: School of Business, Indiana University. (1980b), "A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions," Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (November), 460-9. (1981), "Measurement and Evaluation of Satisfaction Process in Retail Settings," Journal of Retailing, 57 (Fall), 29-31. Olshavsky, R. W. and J. A. Miller (1972), "Consumer Expectations, Product Performance and Perceived Product Quality," Journal of Marketing Research, 9 (February), 1921. Olson, J. C. and P. A. Dover (1979), "Disconfirmation of Consumer Expectations Through Product Trial," Journal of Applied Psychology, 64 (April), 179-89. Russo, E. (1979), "ConsumerSatisfaction/Dissatisfaction: An Outsider's View," in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 6, W. Wilkie, ed. Miami: Association for Consumer Research. Swan, J. E. (1977), "ConsumerSatisfaction with a Retail Store Related to the Fulfillment of Expectations on an Initial Shopping Trip," in Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, R. L. Day, ed. Bloomington: School of Business, Indiana University, 10-17. and I. F. Trawick (1979), "Triggering Cues and the Evaluation of Products as Satisfactory or Dissatisfactory," in Educators' Conference Proceedings, N. Beckwith et al., eds. Chicago: American Marketing Association, 231-4. and (1981), "Disconfirmation of Expectations and Satisfaction with a Retail Service," Journal of Retailing, 57 (Fall), 49-67. Thibout, J. W. and H. H. Kelley (1959), The Social Psychology of Groups. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Warshaw, P. R. (1980), "Predicting Purchase and Other Behaviors from General and Contextually Specific Intentions," Journal of Marketing Research, 17 (February), 26-33. Weaver, D. and P. Brickman (1974), "Expectancy, Feedback and Disconfirmation as Independent Factors in Outcome Satisfaction," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30 (3), 420-8. Westbrook, R. A. and J. W. Newman (1978), "An Analysis of Shopper Dissatisfaction for Major Household Appliances," Journal of Marketing Research, 15 (August), 45666. and R. L. Oliver (1980), "Developing Better Measures of Consumer Satisfaction: Some Preliminary Results," in Advances in Consumer Research, K. B. Monroe, ed. Ann Arbor: Association for Consumer Research, 94-9. This content downloaded from 132.64.30.218 on Sat, 12 Oct 2013 07:33:21 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions