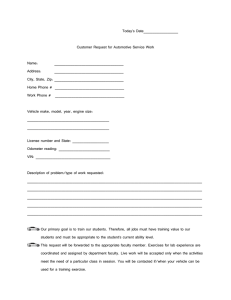

Industry guidelines

advertisement