Seismic Evaluation of 196 kV Porcelain Transformer Bushings

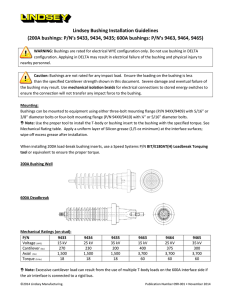

advertisement