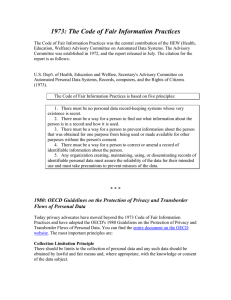

Data Protection - Electronic Privacy Information Center

advertisement