Do Cash Transfers Improve Birth Outcomes? Evidence from

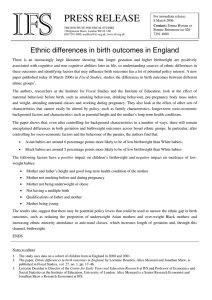

advertisement