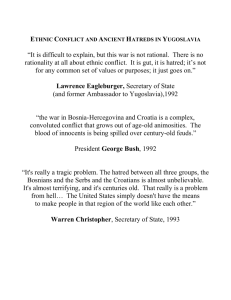

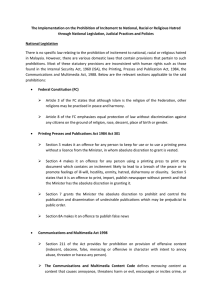

Expert workshop on the prohibition of incitement to national

advertisement