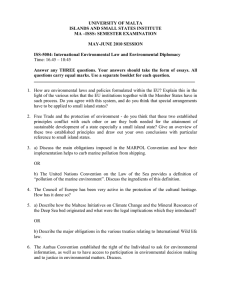

Human Rights and the Environment

advertisement